This is the first in an occasional series in which Venetian Red interviews a contemporary artist about recent work.

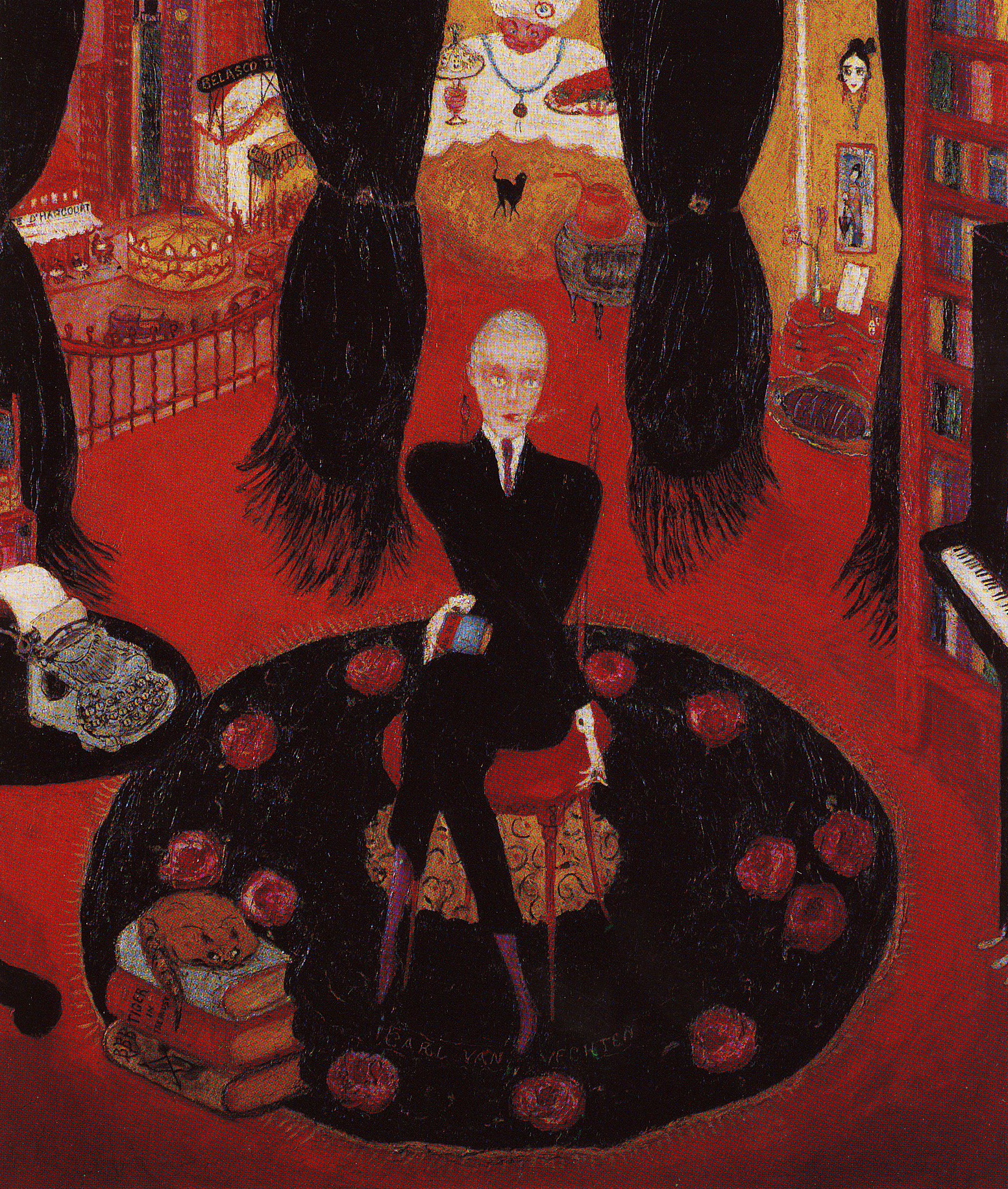

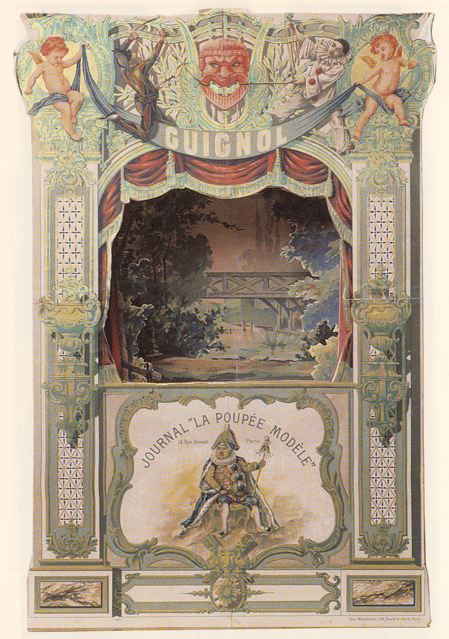

Stephanie Peek, Glimmering, 2009

Stephanie Peek, Glimmering, 2009

Oil on linen, 30″ x 30″

Venetian Red: What was the inspiration for the paintings in Uncertain Riches, your current exhibition at Triangle Gallery?

Stephanie Peek: When I was looking for ways to add color to my Dark Arcadia series (night garden paintings done at the American Academy in Rome and during a Borsa di Studio in the gardens of La Pietra in Florence), an old friend emailed me images of Dutch still lifes he had recently collected, which I have dropped into the dark atmosphere of the night gardens.

I have floated tulips, roses and other flowers from 17th century still life paintings through the dark smoky atmosphere of my earlier paintings of night gardens. The dramatic light and rich colors refer to the work of Dutch painter Rachel Ruysch. The softer, lighter paintings reflect the melancholy of early 18th century French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau.

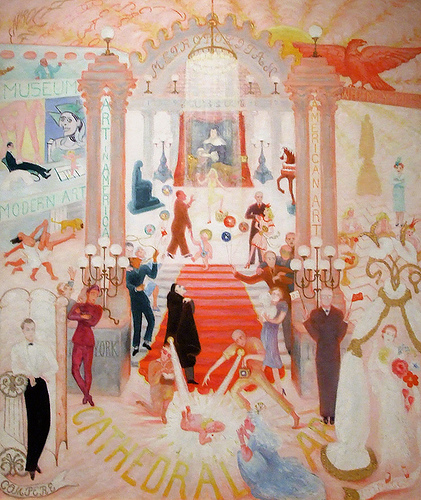

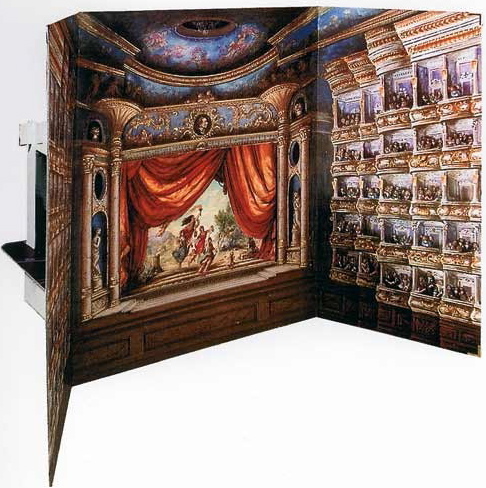

Stephanie Peek, Watteau II, 2009

Stephanie Peek, Watteau II, 2009

Oil on panel, 20″ x 20″

Venetian Red: Why are you painting flowers at this time in your career?

Stephanie Peek: I find that painting can be a site of meditation, suspending time, making time irrelevant, and can put me in touch with that which does not decay. Suspended in silence, flowers speak for me—of fragile beauty and the ephemeral nature of worldly delights.

Venetian Red: This work creates an extremely elegiac, contemplative mood.

Stephanie Peek: These paintings refer to the tradition of memento mori (falling flowers being more subtle than skulls), The Embarrassment of Riches by Simon Schama, and our contemporary version of “tulipmania.” Materiality cannot be trusted—and yet, how beautiful, even luscious, painting can be. Vita brevis, ars longa.

Venetian Red: Can you talk about the source material for these paintings?

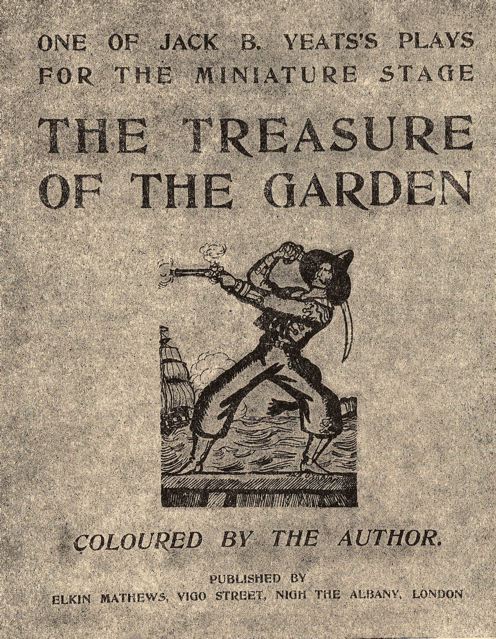

Stephanie Peek: Referring to the hybrid nature of our culture, I used as sources not only photographs of paintings of flowers, but also photographs of flowers in my neighborhood, actual live flowers in my studio, artificial flowers from roadside memorials—and a few invented ones too.

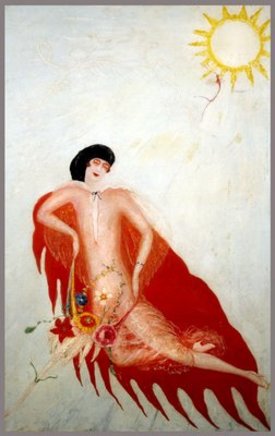

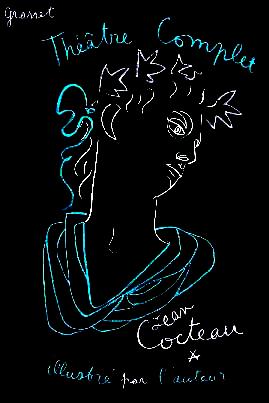

Stephanie Peek, Requiem, 2009

Stephanie Peek, Requiem, 2009

Oil on panel, 30″ x 30″

Venetian Red: In your work you return again and again to nature and the garden. Tell us about how these themes have evolved over recent years.

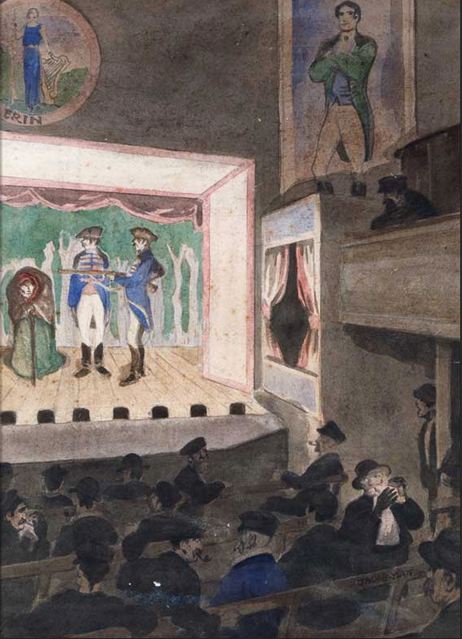

Stephanie Peek: After working with the idea of the garden as a refuge for several years, it was natural for me to return to that safe place after 9/11. I “protected” this space by camouflaging the garden, dissolving the edges of the forms and bringing the background to the foreground, going simultaneously flat and deep. Thus an overall pattern of marks developed on the surface which became increasingly complex.

This led me to the study of the history of military camouflage in a series called Uniform Language. At the beginning of the 20th century, American painter Abbot Thayer had introduced his studies of the “concealing coloration” of animals and birds in nature to the United States military for use in concealing ships, weapons and soldiers. Governments throughout the world hired artists to design a wide variety of camouflage depending on the environment.

My intent was to reclaim these patterns of concealment by re-contextualizing the camouflage of countries in the news into abstract paintings, translating these patterns from military usage to a more peaceful purpose.

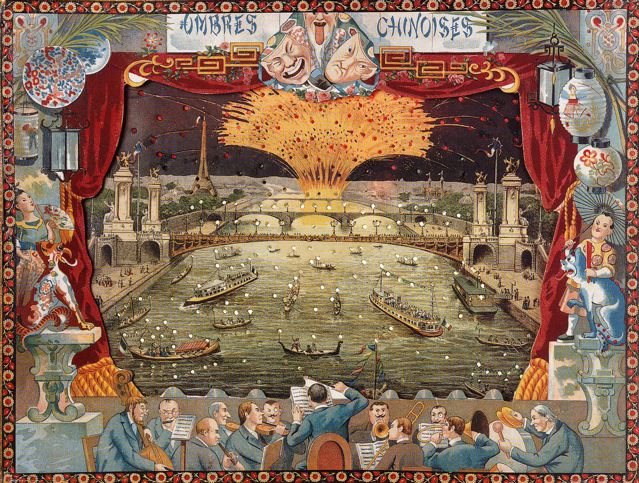

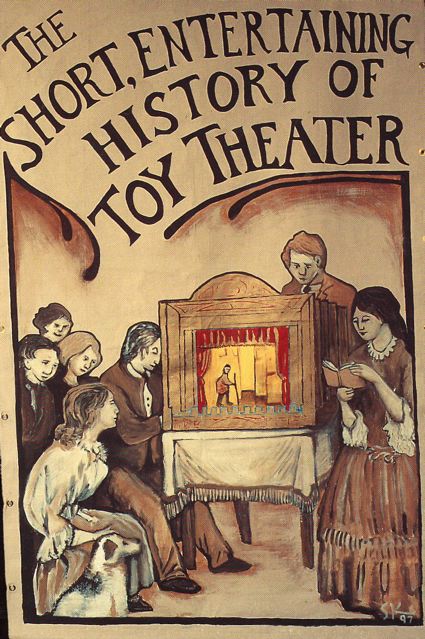

Stephanie Peek, Survival Tactics, 2002

Stephanie Peek, Survival Tactics, 2002

Oil on canvas, 80″ x 70″

Venetian Red: I’m very interested in the way you explore nature as pattern, can you talk a bit about that?

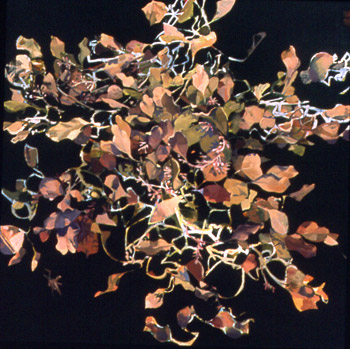

Stephanie Peek: For years the subject central to my art practice has been nature: from gardens as refuge, camouflage patterns and the complex compilations of fragments of color seen in leaves.

A spray of dried eucalyptus leaves in my studio was my subject for three years, and heightened my attention to the most minute of differences and variations in shifting viewpoints with each painting.

In revisiting the classic genre of still life my project was to translate light into color.

These leaves provided the occasion for a study of the subtle shifts of hue from dusty roses to cool green. Analyzing colors in these leaves, in their shadows and reflections, in the grounds, resulted in multitudinous color patches which formed patterns of brush marks on the surface of the paintings.

When I pulled back from a concentrated focus on the color relationships, I was surprised to see a kind of joy in these paintings. The melancholy quality of evanescence implicit in the subject of dried leaves was transcended through attention to the colors right in front of my eyes.

Stephanie Peek, Dark Light, 2005

Stephanie Peek, Dark Light, 2005

Oil on canvas, 45″ x 45″

Stephanie Peek’s current show, Uncertain Riches, is at Triangle Gallery in San Francisco through October 17, 2009.