On his first trip to France in 1855, the 21-year-old William Morris wrote to his mother: “I do not hope to be great at all in anything, but perhaps I may reasonably hope to be happy in my work.” This, for me, sums up Morris’ greatness: his prodigious energy, insatiable curiosity and passion had the underpinnings of a tremendous work ethic, moral integrity and true decency. When Morris died in 1896, at the age of 62, his doctor said the cause of death was simply “being William Morris.” And no wonder—Morris was a poet, novelist, bibliophile, translator, embroiderer, calligrapher, engraver, gardener, decorator, dyer, weaver, architectural preservationist and Socialist. He designed furniture, printed and woven textiles, stained glass, tiles, carpets, tapestry, murals, wallpaper, books and type. An early environmentalist, the floral designs for which he is famous were informed by his knowledge of horticulture and inspired in part by medieval tapestries and the many gardens he planted and tended.

On his first trip to France in 1855, the 21-year-old William Morris wrote to his mother: “I do not hope to be great at all in anything, but perhaps I may reasonably hope to be happy in my work.” This, for me, sums up Morris’ greatness: his prodigious energy, insatiable curiosity and passion had the underpinnings of a tremendous work ethic, moral integrity and true decency. When Morris died in 1896, at the age of 62, his doctor said the cause of death was simply “being William Morris.” And no wonder—Morris was a poet, novelist, bibliophile, translator, embroiderer, calligrapher, engraver, gardener, decorator, dyer, weaver, architectural preservationist and Socialist. He designed furniture, printed and woven textiles, stained glass, tiles, carpets, tapestry, murals, wallpaper, books and type. An early environmentalist, the floral designs for which he is famous were informed by his knowledge of horticulture and inspired in part by medieval tapestries and the many gardens he planted and tended.

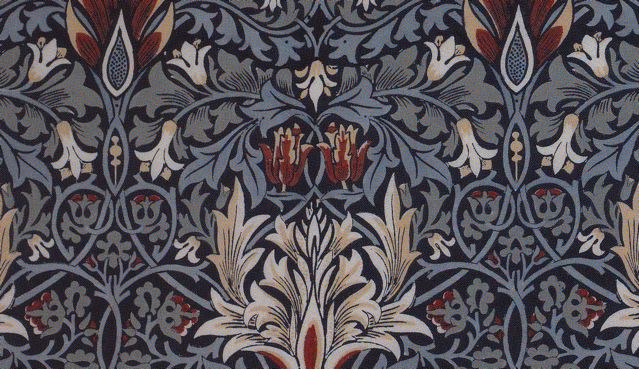

William Morris, design for Iris, printed cotton, c.1876

William Morris, design for Iris, printed cotton, c.1876

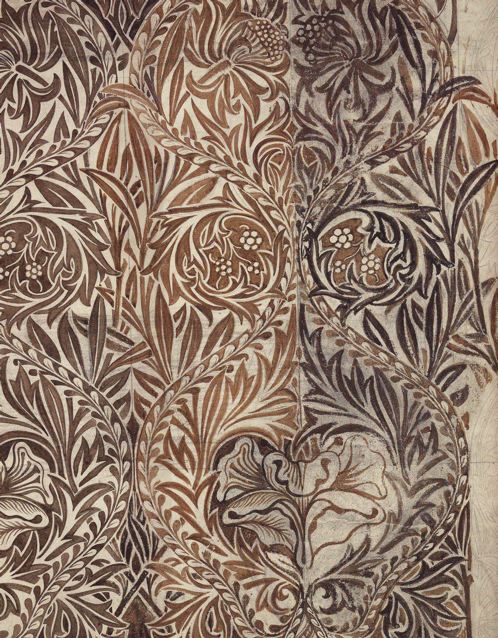

William Morris, Jasmine, wallpaper, 1872

William Morris, Jasmine, wallpaper, 1872

In 1847, after an idyllic childhood, Morris was sent away to Marlborough College a few months after the death of his father. He hated the school but loved the surrounding landscape and spent as much time as possible roaming the countryside. While at Marlborough, Morris abandoned his family’s tame Protestantism and embraced the music, ritual and aesthetics of Anglo-Catholicism. When he went up to Oxford in 1853, he intended to devote his life to God, but he soon abandoned the church for art. He always had a taste for things medieval and Gothic—it is said that he read the novels of Walter Scott at age 4. While at Oxford, he was very influenced by the work of John Ruskin, especially his essay “The Nature of Gothic” in his book The Stones of Venice. Oxford was also where he met his life-long friend, the painter Edward Burne-Jones, the son of a gilder from Birmingham who educated Morris about the plight of working-class laborers.

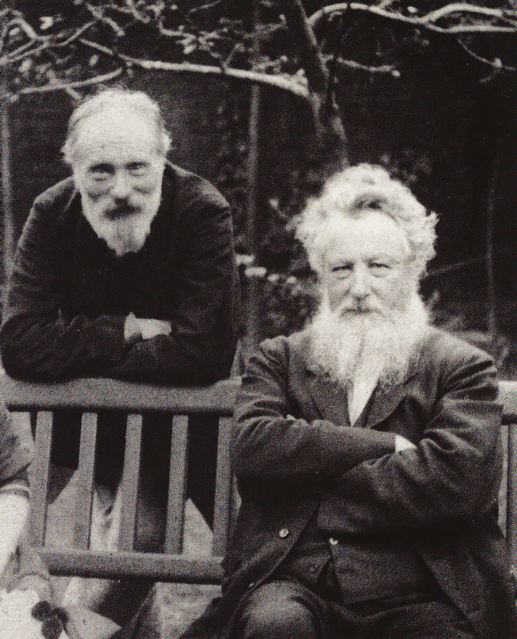

Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, 1890

Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, 1890

photo:William Morris Gallery, London

William Morris was a Renaissance man in Victorian times. He is considered to be the founder, along with John Ruskin, of the Arts & Crafts movement. In his lecture, The Beauty of Life, given in 1880, Morris said: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” He despised the aesthetic failings of the machine age and the division of labor that broke down production, from design to execution, into separate tasks. He extolled the joys of handwork and the integrity of creative labor. He wanted to unify art and craftsmanship. He wrote: “If I were to say what is at once the most important production of art and the thing most longed for, I should answer, a beautiful house.”

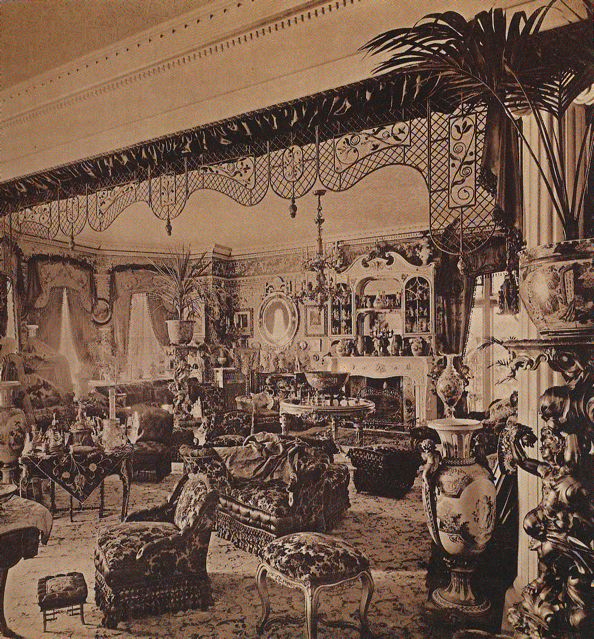

A William Morris interior was the antithesis of the Victorian aesthetic of overstuffed rooms, draped with endless yards of fabric, filled with memorabilia, potted plants and heaps of mass-produced decorative embellishments.

Victorian drawing Room, Wickham Hall, Kent, 1897

Victorian drawing Room, Wickham Hall, Kent, 1897

Even though Morris combined densely patterned carpets, upholstery and wallpaper, the designs, influenced by nature but with orderly, flat areas of color and a graceful linear quality, had a clean simplicity and elegance.

Earlier I mentioned Morris’ decency. He insisted on a pleasant environment for his workers and his workshops were filled with light and air.

Merton Abbey, hand-blocking chintz in the print shop

Merton Abbey, hand-blocking chintz in the print shop

He also believed everyone should have access to beautiful things: “What business have we with art, unless we can all share it?” He was a man who embodied enormous contradictions: an environmentalist who derided industrialization and urbanization, yet spent much of his life working in London; a Socialist who designed luxury goods for the wealthy and predicted the demise of capitalism. This latter conflict, in part, led Morris away from design into activism and book publishing, but not before appointing his disciple, the extremely talented John Henry Dearle, as the chief designer at Morris & Co.

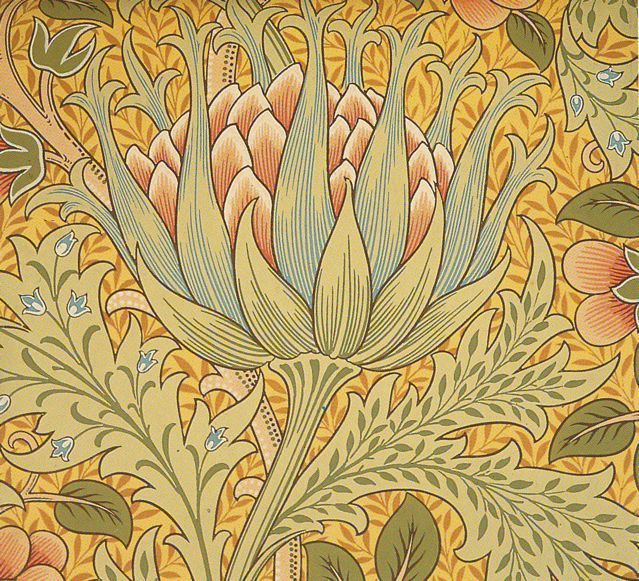

John Henry Dearle, Artichoke wallpaper, 1899

John Henry Dearle, Artichoke wallpaper, 1899

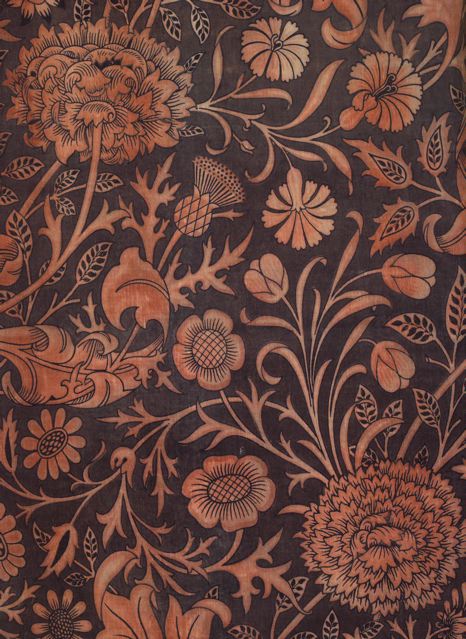

John Henry Dearle, Cherwell, wall hanging, 1897

John Henry Dearle, Cherwell, wall hanging, 1897

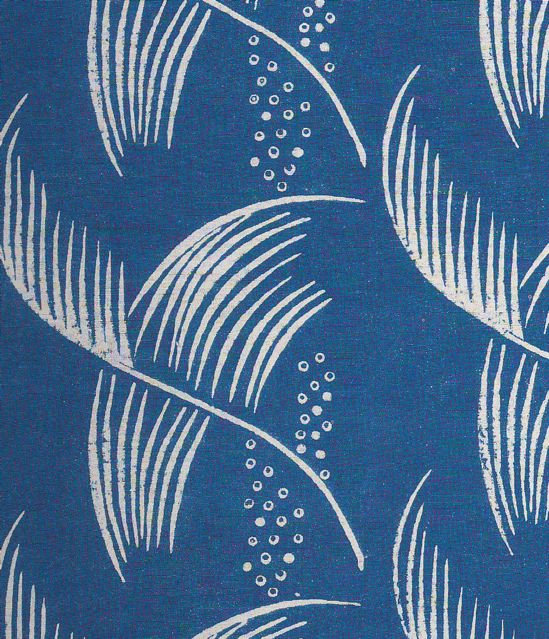

Block printed velveteen

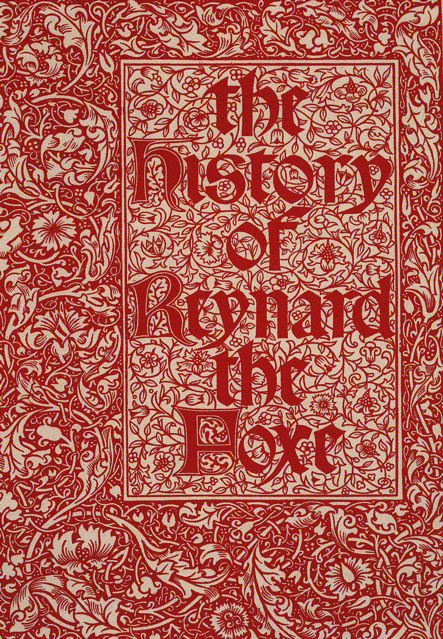

Morris devoted the last 10 years of his life to book publishing. Dissatisfied with the state of British publishing, he founded the Kelmscott Press “with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty.” Not surprisingly, it was very important to Morris for his books to have a strong visual element and they were filled with exquisite detail, including illustrations, decorative motifs and printed cloth book covers.

William Morris, The Roots of the Mountains (London, Chiswick Press, 1890), bound in Honeysuckle printed cotton

William Morris, The Roots of the Mountains (London, Chiswick Press, 1890), bound in Honeysuckle printed cotton

William Morris, for the Kelmscott Press

William Morris, for the Kelmscott Press

Proof, title-page, The History of Reynard the Fox, 1893

Even more significant than his own prodigious output is the role Morris played as a catalyst, leaving an enormous legacy to craftsmen, designers, writers, publishers and politicians. He also inspired the founding of many schools and guilds devoted to the Arts & Crafts aesthetic.

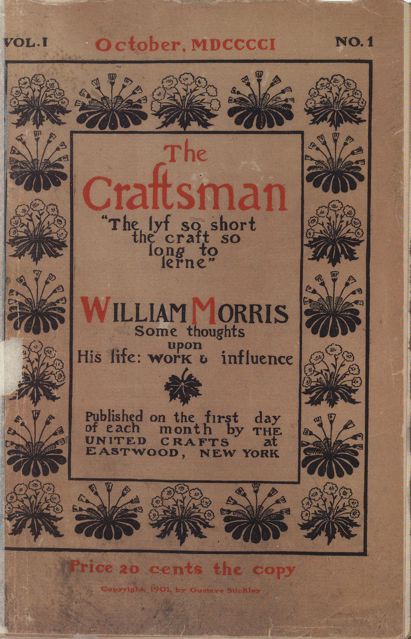

The Craftsman, October 1901

The Craftsman, October 1901

(The first issue, dedicated to William Morris)

William Morris contributed to, and inspired, the renaissance of British craftsmanship which led to an exciting new generation of British textile designers—Dorothy Larcher, Phyllis Barron, Enid Marx among many others. These designers embraced many of Morris’ ideals, but were determined to develop a new, more international aesthetic—experimenting with vegetable dyes, block-printing and traditional hand weaving techniques and taking inspiration from Italian, Scandinavian and Eastern European folk art. Some, inspired by the Bauhaus in Weimar, moved into industrial production.

Dorothy Larcher, Small Feather, block-printed linen, 1930s

Dorothy Larcher, Small Feather, block-printed linen, 1930s

Morris loved beauty and nature but especially delighted in the man made co-existing in harmony with nature—and every beautiful object he created in his intensely productive life was a tribute to that vision.

“My work is the embodiment of dreams in one form or another.” Letter to Cornell Price, Oxford, 1856.