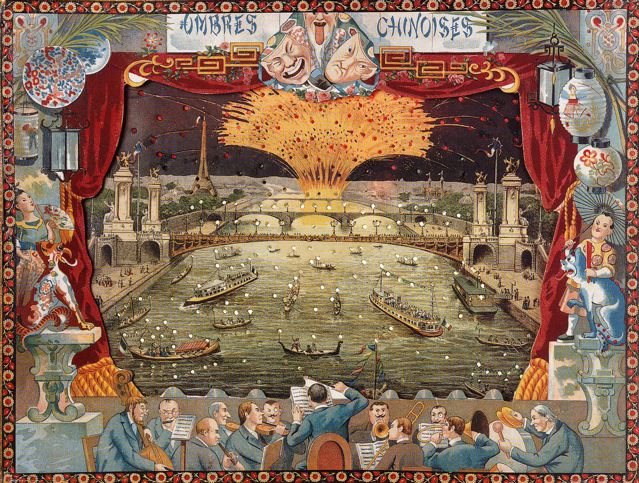

Ombres Chinoise, A Toy Theater

Ombres Chinoise, A Toy Theater

Fireworks on the Seine during the Exhibition Universelle, Paris 1900

Mauclair-Dacier, French, colored lithograph, 13 7/8 x 18 1/4in.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein

Act One: “A Penny Plain, Twopence Coloured”

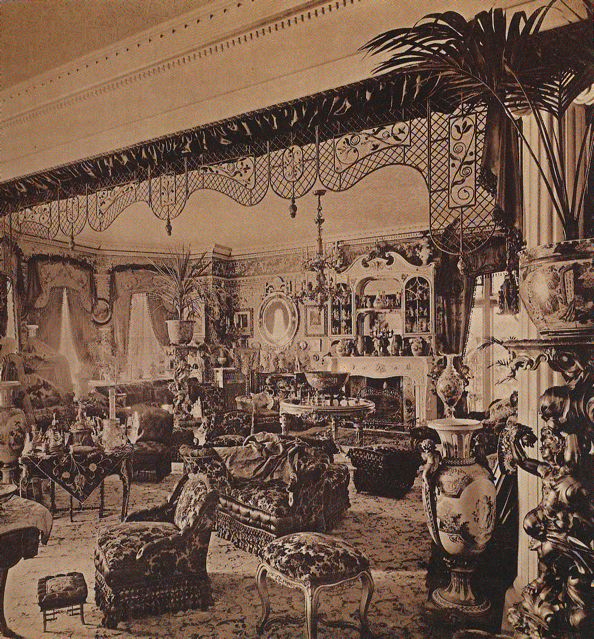

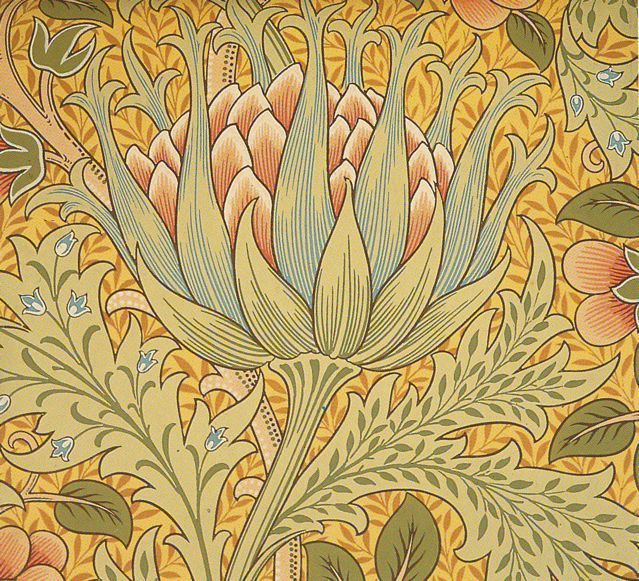

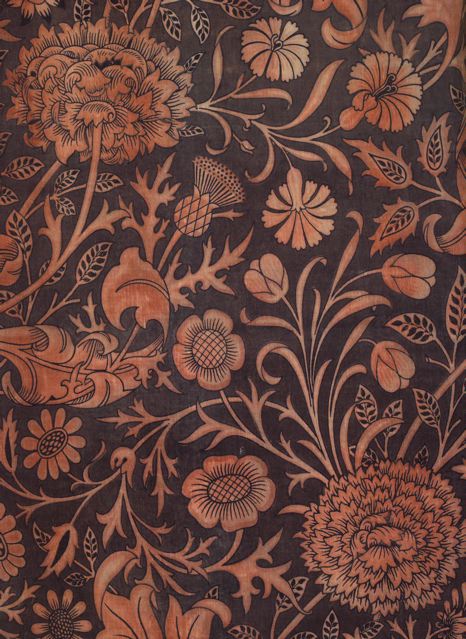

The history of miniature theater, once a very popular form of domestic entertainment, is fascinating and engaging. Toy theaters flourished in 19th-century England where it was known as Juvenile or Toy Theatre. It was also popular throughout Europe—Papiertheater in Germany, Teatrini di Carta in Italy, Kindertheater in Austria, Imagerie Francais in France, El Teatro de los Ninos in Spain and the Dukketeater in Denmark. With some variations, the format was essentially the same—characters and scenery (complete with back drops, side wings, top drops and prosceniums) were printed on paper. Children then colored these sets and figures, cut them out, mounting some pieces on cardboard or light wood. The characters in the dramas were sometimes attached to flat wooden sticks that were moved across the the stage from side to side. On these tiny stages, large dramas were enacted.

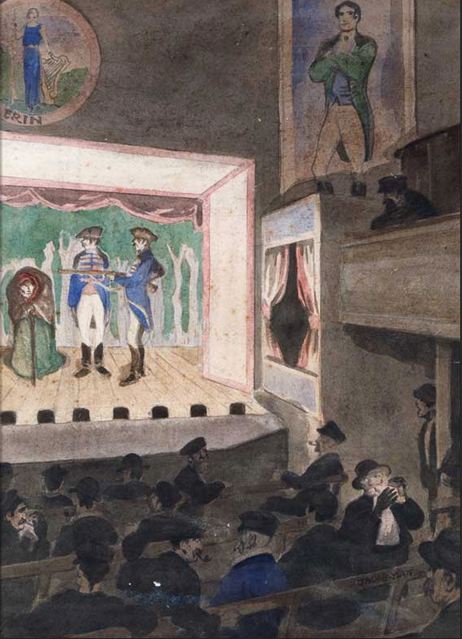

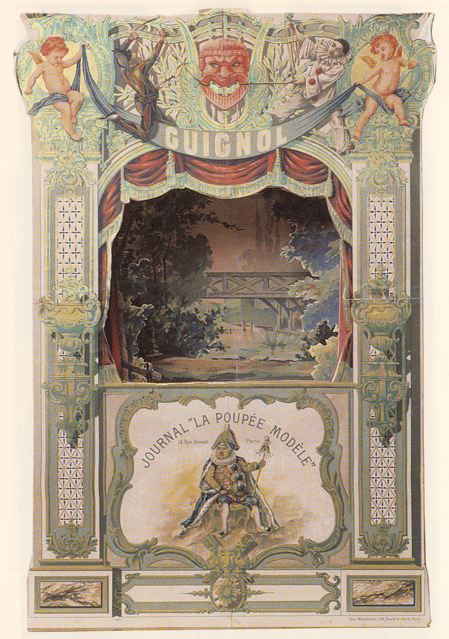

Guignol, France, 1900s

Guignol, France, 1900s

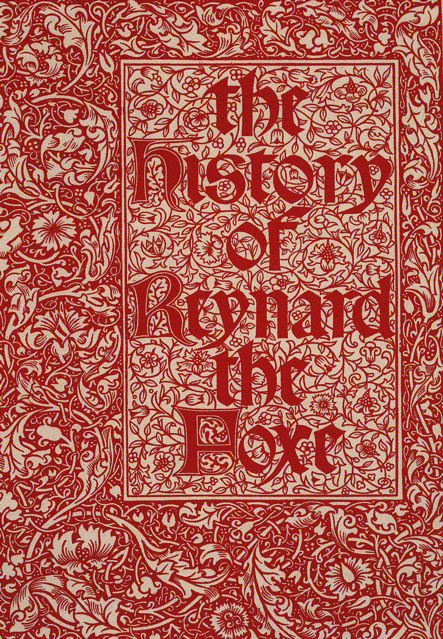

In England, the early theaters were printed from copper-plate engravings and could be purchased colored or uncolored—hence the catchphrase “a penny plain and twopence coloured.” Because these theaters were exact reproductions of sets and scenery being presented on the contemporary stage, these theaters often provide the only visual record of the history of the London stage of that period. The toy theaters in England were predominantly melodramas and pantomimes, and plays by Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott.

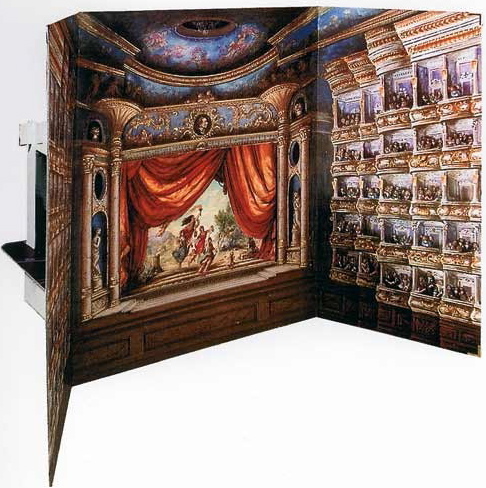

Toy Theatre by A. How Mathews, England, c1900

Toy Theatre by A. How Mathews, England, c1900

courtesy Peter Baldwin

In Germany, they were often plays by Goethe, Schiller and their contemporaries; and operas by Wagner, Mozart and Rossini as well as popular comic operas of the day. In Denmark, beginning in around 1880, the firm of Jacobsen printed colored lithographs for theaters largely depicting plays about Danish history and the fairy tales of Hans Christian Anderson. Many of these are still published today by the firm of Prior, in Copenhagen.

Dukketeater, Prior, Copenhagen

Dukketeater, Prior, Copenhagen

In England, paper theater began with William West, who first sold sheets of characters for the popular pantomime, Mother Goose, in 1811, and soon went on to publish sets and characters for a number of plays then enjoying success in London. These were very popular and other publishers joined in. Eventually, the style of theater productions changed and became less suitable for toy theater production—after 1860 only a couple of publishers continued to produce and hand-color the old plays up until the 1930s. One of these publishers was Benjamin Pollock. After the war, production was revived, and Pollock’s plays and theaters, now printed in color, can still be purchased today at Pollock’s Toy Museum in London.

Interior of Pollock’s Toy Museum

Interior of Pollock’s Toy Museum

The fascinating history of toy theaters, lavishly illustrated and discussed in great detail, can be found in Toy Theatre, edited by Kenneth Fawdry, (published by Pollock’s Toy Theatres Ltd., London) and Peter Baldwin’s excellent Toy Theatres of the World (Zwemmer, London, 1992.)

Toy Theatre display, Pollock’s Toy Museum, London

Toy Theatre display, Pollock’s Toy Museum, London

Act Two: Not For Pleasure Alone

One of the most fascinating things about toy theaters is that while adults enjoyed them as well, they were intended for children. Imagine the dexterity, concentration, imagination and thoughtfulness required to assemble and produce these performances. Quite a far cry from the offerings of today’s dumbed-down children’s entertainment industry. These miniature impresarios took their work very seriously—sets were constructed, speaking parts rehearsed, musical accompaniment (usually piano, perhaps a small ensemble) organized. The footlights were tiny candles with metal reflectors. Often tickets were sold at the door. This was a total performance experience.

For a wonderful glimpse of the magic of toy theater, watch the opening scene from Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece, Fanny and Alexander. About 35 seconds in, you will see Alexander playing with his toy theater. Notice that his theater has the motto of the Royal Theater in Copenhagen inscribed on the proscenium: “Ej Blot Til Lyst”—Danish for Not for Pleasure Alone.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0O9DcvCCI4]

However, toy theater also had its adult enthusiasts—Goethe was inspired to write for the theater by home performances he saw as a child. Robert Louis Stevenson wrote lovingly of stopping in the street and peering into the window of a shop in Edinburgh that displayed a working miniature theater. G.K. Chesterton was a life-long aficionado of toy theater. Here he is, cutting out characters for his miniature theater play, George and the Dragon:

Chesterton wrote: “Has not everyone noticed how sweet and startling any landscape looks when seen through an arch? This strong, square shape, this shutting off of everything else, is not only an assistance to beauty; it is the essential of beauty…

This is especially true of toy theatre, that by reducing the scale of events it can introduce much larger events…Because it is small it could easily represent the Day of Judgement. Exactly in so far as it is limited, so far it could play easily with falling cities or with falling stars.”

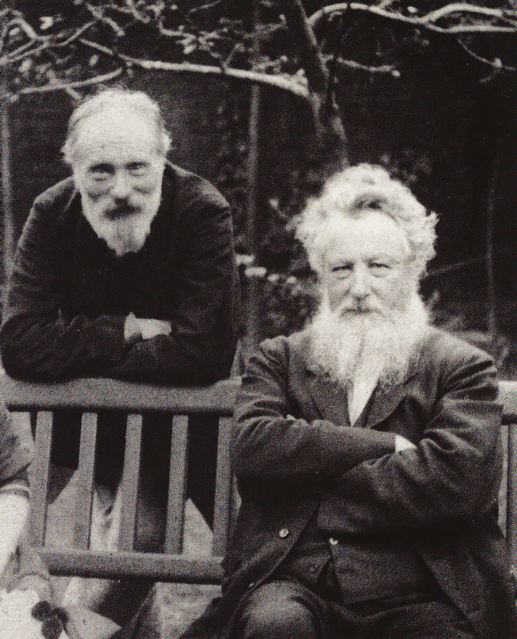

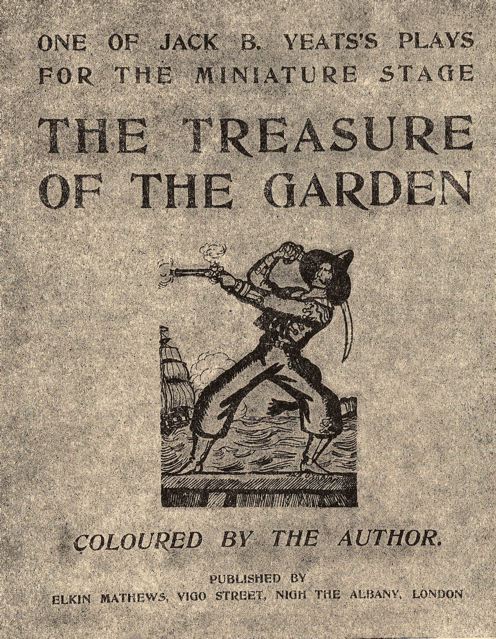

The artist Jack Butler Yeats, son of painter John B. Yeats and brother of poet William B. Yeats, loved toy theater, and wrote and performed plays every Christmas for local children. Included in Jack B. Yeats, Collected Plays, is Yeats’ introduction to his plays for toy theater, My Miniature Theatre. In it Yeats says: “As to the plays, I write them myself. So what shall I say of them but that I like the piratical ones best.”

Photo courtesy The Collected Plays of Jack B. Yeats by Robin Skelton

Photo courtesy The Collected Plays of Jack B. Yeats by Robin Skelton

Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1971

Yeats designed sets for the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, which also produced three of his own plays. This watercolor, of a performance at the Old Mechanics’ Theatre (later the Abbey) wonderfully invokes his enthusiasm for the theater—both large and small.

Jack B. Yeats, Willy Reilly at the Old Mechanics’ Theatre

Watercolor, Courtesy of the Abbey Theatre

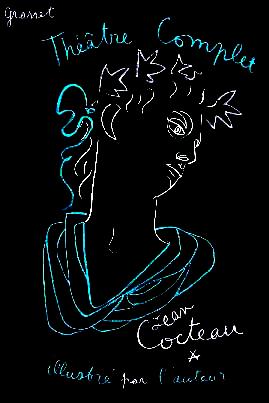

Another toy theater aficionado, the writer Jean Cocteau, said: “When I had scarlet fever or German measles and was kept in bed…I would design scenery for my toy theater…I think that was when I caught the red and gold disease of the theater, from which I never recovered.”

Act Three: Toy Theater today

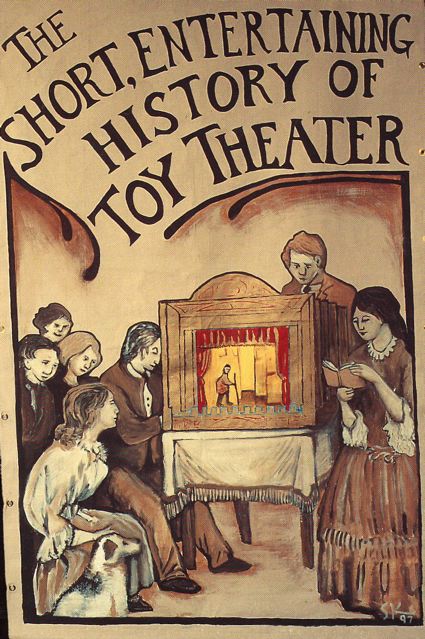

Stephen Kaplin, banner for Great Small Works’ Travelling Toy Theater Festival, 1997

Stephen Kaplin, banner for Great Small Works’ Travelling Toy Theater Festival, 1997

photo by Jeff Becker

Traditional toy theaters, now understandably difficult to find, are avidly collected by antiquarians and Pollock’s produces 20,000 reproduction toy theaters a year. However, the love of miniature theater is not just an exercise in nostalgia, there is a thriving international community of toy theater enthusiasts who create wonderful contemporary works of wildly varying content and complexity.

Great Small Works has produced seven Toy Theater Festivals that have featured the work of hundreds of theater and visual artists from around the world. I invite you to take a minute to peruse their web site and find links to information about upcoming performances and festivals.

In closing, here is a wonderful newsreel from the 1920s which shows Mr. Pollock printing and constructing a toy theater. Feel free to try this at home!

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=senXvAJWxgw]