Portrait of Dagobert Peche, c.1920

Portrait of Dagobert Peche, c.1920

Dagobert Peche (1887-1923) was a brilliant, versatile and eclectic designer who, in fewer than 10 years with the Wiener Werkstätte, created more than 3000 decorative objects of great beauty, energy and imagination that were full of movement, light and playfulness. Peche’s decorative objects were wonders of linear grace and inventiveness; his jewelry designs were exquisite miniature sculptures; and his textile and wallpaper designs, with their extraordinary radiant color and pattern, are perhaps his greatest legacy.

Dagobert Peche, Jewel Box, 1920

Dagobert Peche, Jewel Box, 1920

Josef Hoffmann, the founder, along with Koloman Moser, of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, said upon Peche’s premature death at the age of 36:

Dagobert Peche was the greatest ornamental genius Austria has produced since the Baroque Age…All of Germany has arrived at a new stylistic epoch thanks to Peche’s patterns.

Dagobert Peche, Schwalbenschwantz, fabric, 1911/13

Dagobert Peche, Schwalbenschwantz, fabric, 1911/13

Josef Hoffman and Kolo Moser, who both taught at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Art), founded the Wiener Werkstätte in Vienna in 1903. They were influenced by the ideas of John Ruskin and William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement in England and inspired by their work in establishing a creative interaction of art, design and craftsmanship. Hoffman and Moser published a brochure outlining this philosophy of Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) in 1905:

The limitless harm done in the arts and crafts field by low-quality mass production on the one hand and by the unthinking imitation of old styles on the other is affecting the whole world like some giant flood…It would be madness to swim against this tide. Nevertheless, we have founded our workshop…

We seek to establish close contact between the public, designer and craftsman, and to create a good and simple household object. We start with function, usefulness is our first requirement. Our strength lies in good proportions and proper use of materials. Where possible, we shall attempt to be decorative, but not compulsively so and not at any cost. The value of artistic work and its design needs to be acknowledged and appreciated once more. The work of craftsman is to be held to the same standard as that of the painter and sculptor. We cannot and will not compete with cheapness; it is mainly achieved at the expense of the worker, and we feel that recapturing for him the joy of creation and a humane existence is our foremost obligation…

They did not want to rely on overly expensive materials, especially in their jewelry, so they used a lot of silver, gilt, enamel, and semi-precious stones—but no diamonds, rubies and emeralds.

Initially, the aesthetic of the Wiener Werkstätte and Josef Hoffmann was one of simplicity, clarity of shape (often square), and a strict adherence to form. When Peche joined the Wiener Werkstätte, his more fluid, ornamental style began to dominate.

Josef Hoffmann, seated in a chair of his own design, c.1890

Josef Hoffmann, seated in a chair of his own design, c.1890

Josef Hoffmann, Cigarette case, 1912

Josef Hoffmann, Cigarette case, 1912

Josef Hoffmann, Pot, porcelain, c.1905

Josef Hoffmann, Serving spoon,c.1905

Dagobert Peche was born in Lungau, Austria in 1887. He wanted to be a painter, but his older brother Ernst claimed that role, so Dagobert went to Vienna in 1906 and trained as an architect at the Technische Hochschule. In 1911, at a banquet honoring Austrian architect Otto Wagner on his seventieth birthday, he met Josef Hoffmann. Peche did freelance textile design for the Wiener Werskätte from 1912 to 1915, when Hoffmann invited him to become a full member. In 1917, after a brief, unsuccessful stint in the army, Peche moved to Zürich to take charge of the new Wiener Werkstätte branch there.

Wiener Werkstätte shop, Zurich, 1917

Wiener Werkstätte shop, Zurich, 1917

Peche had gone to secondary school in Stüttgart where became interested in Baroque and Rococo design. He also greatly admired the work of Aubrey Beardsley and was passionate about ornamentation. To Peche’s credit, he incurred the wrath of Adolf Loos by gilding the apples on a tree with gold leaf—unable to see the beauty or humor, Loos fumed that Peche had destroyed a whole year’s crop. In his polemic, Ornament and Crime, written in 1908, Loos wrote that “ornamentation was a grotesque relic of humanity’s unwholesome past.”

Dagobert Peche, Box in the Shape of an Apple, c.1920

Dagobert Peche, Box in the Shape of an Apple, c.1920

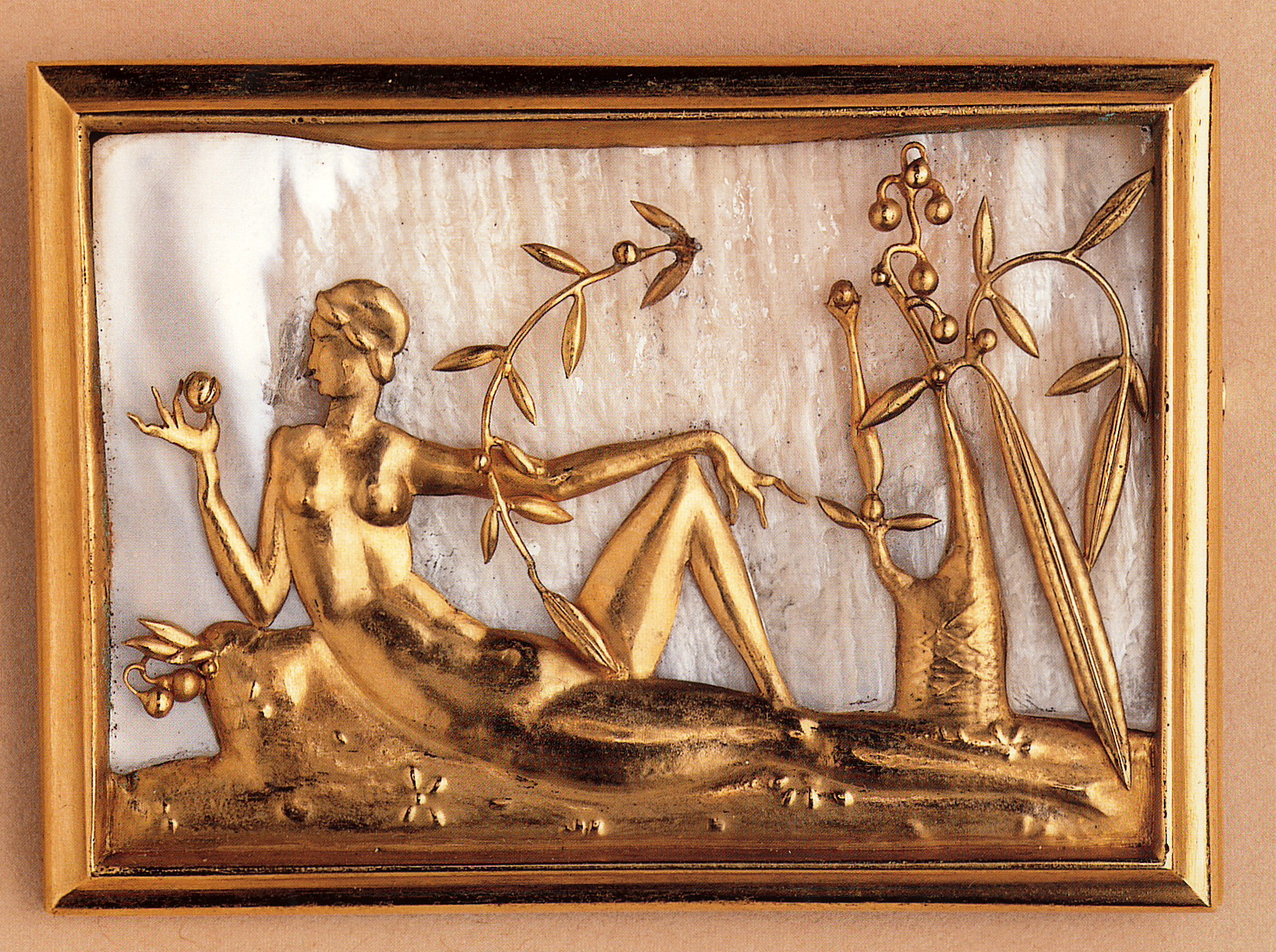

For the Wiener Werkstätte, Peche designed metalwork, ceramics, mirror frames, glass, textiles, wallpaper, furniture, books and jewelry.

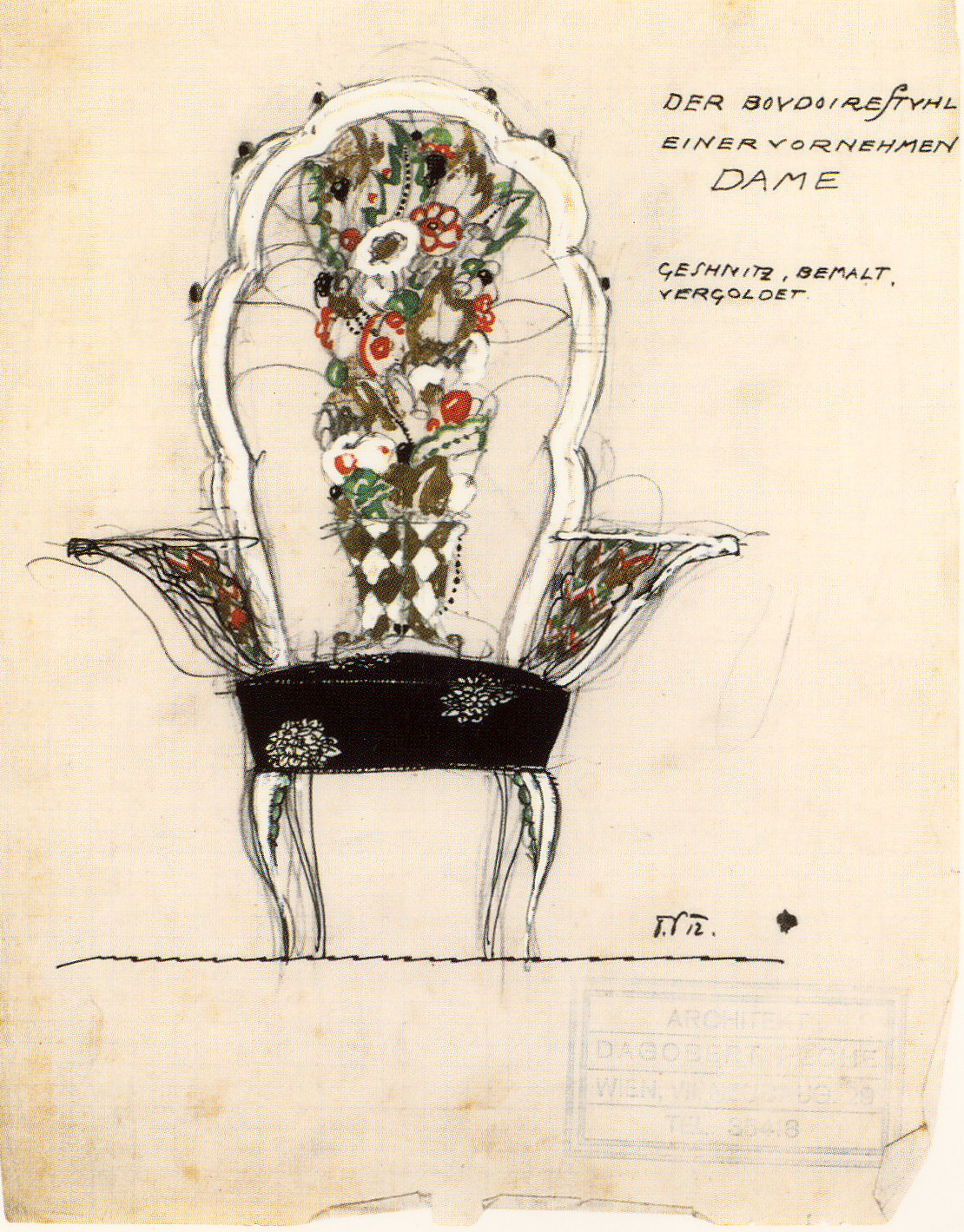

Dagobert Peche, Boudoir Chair for an Elegant Lady, 1912

Dagobert Peche, Boudoir Chair for an Elegant Lady, 1912

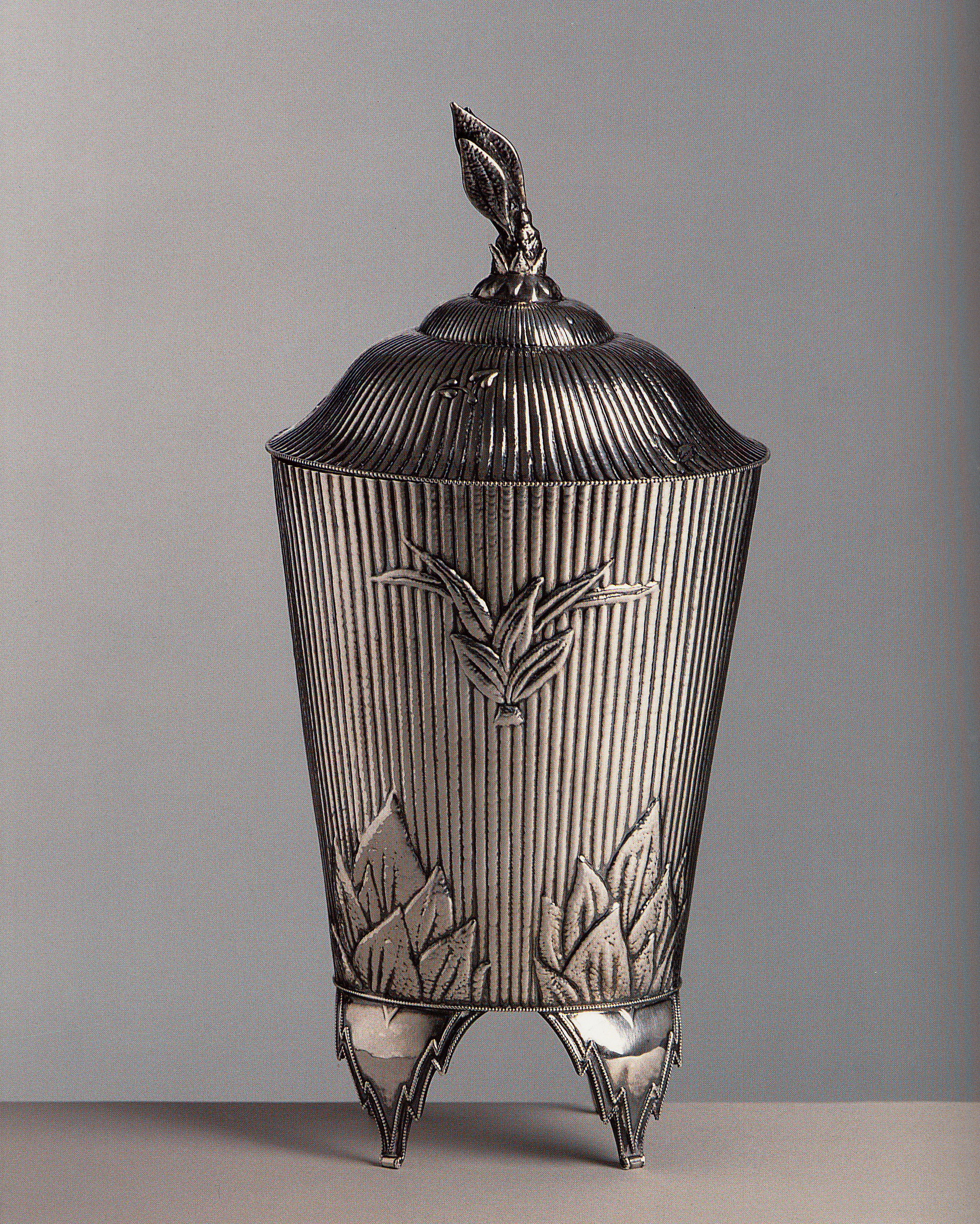

Dagobert Peche, Tea Caddy, 1916

Dagobert Peche, Tea Caddy, 1916

In all these pieces there is a quality of lightness, and a painterly, romantic touch. He integrated ornamentation into his designs, and often camouflaged the object’s function. He was pushing the limits of the Wiener Werkstatte’s philosophy of utilitarian design, but he justified it this way:

It is simply the product of art imposed on craftsmanship. The art enlivens the elements and branches of the craft in which the object to be created requires a certain look. Essentially, all of these are art objects, simply not fine art, for they generally have a function as well.

Dagobert Peche, Bird-shaped Candy Box, 1920

Dagobert Peche, Bird-shaped Candy Box, 1920

Dagobert Peche, Brooch, Zurich, c.1917-19

Dagobert Peche, Diomedes, fabric design, 1919

Dagobert Peche, Diomedes, fabric design, 1919

Dagobert Peche, Wundervogel, wallpaper design, c.1914

Dagobert Peche, Wundervogel, wallpaper design, c.1914

Unlike the British Arts & Crafts movement which hoped to create a socialist state where excellent design and craftsmanship was universally available, improving the quality of life for all, the Wiener Werkstätte did not have such a clear agenda or widespread support. There was only a small segment of artistically engaged, wealthy Austrians who appreciated their efforts—among them the artist Gustav Klimt. His portrait below is of Eugenie Primavesi who, with her industrialist husband Otto, and cousin Robert, acquired a significant financial stake in the Wiener Werkstätte in 1914.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Eugenie Primavesi, c.1913-14

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Eugenie Primavesi, c.1913-14

The Wiener Werkstätte closed in 1932. In future posts, Venetian Red will delve more deeply into the exquisite textiles produced by the Wiener Werkstätte and the interesting people, many of them women, who designed them. We can only imagine what amazing things Dagobert Peche would have designed if his life had not been cut short by a tumor misdiagnosed as TB. Toward the end of his life, Peche became nervous and solitary, and, frustrated with designing only for the wealthy, longed to create beautiful design that could be enjoyed by all.

To see many more examples of Peche’s designs and sketches, I highly recommend Dagobert Peche and the Wiener Werkstätte, Yale University Press, published with the Neue Galerie, New York.

Dagobert Peche, Poster for Wiener Werkstätte Fashions, c.1919

Dagobert Peche, Poster for Wiener Werkstätte Fashions, c.1919