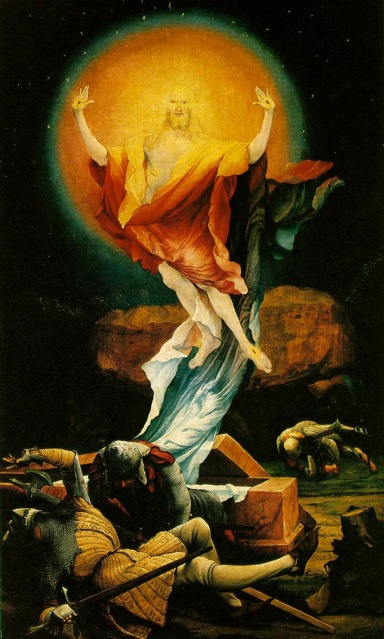

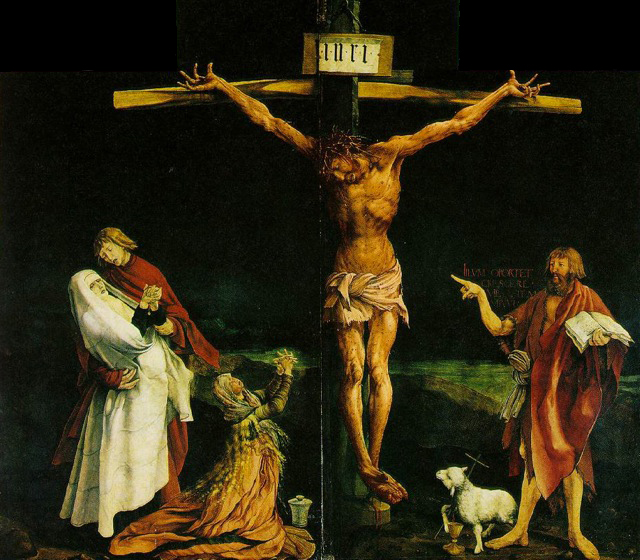

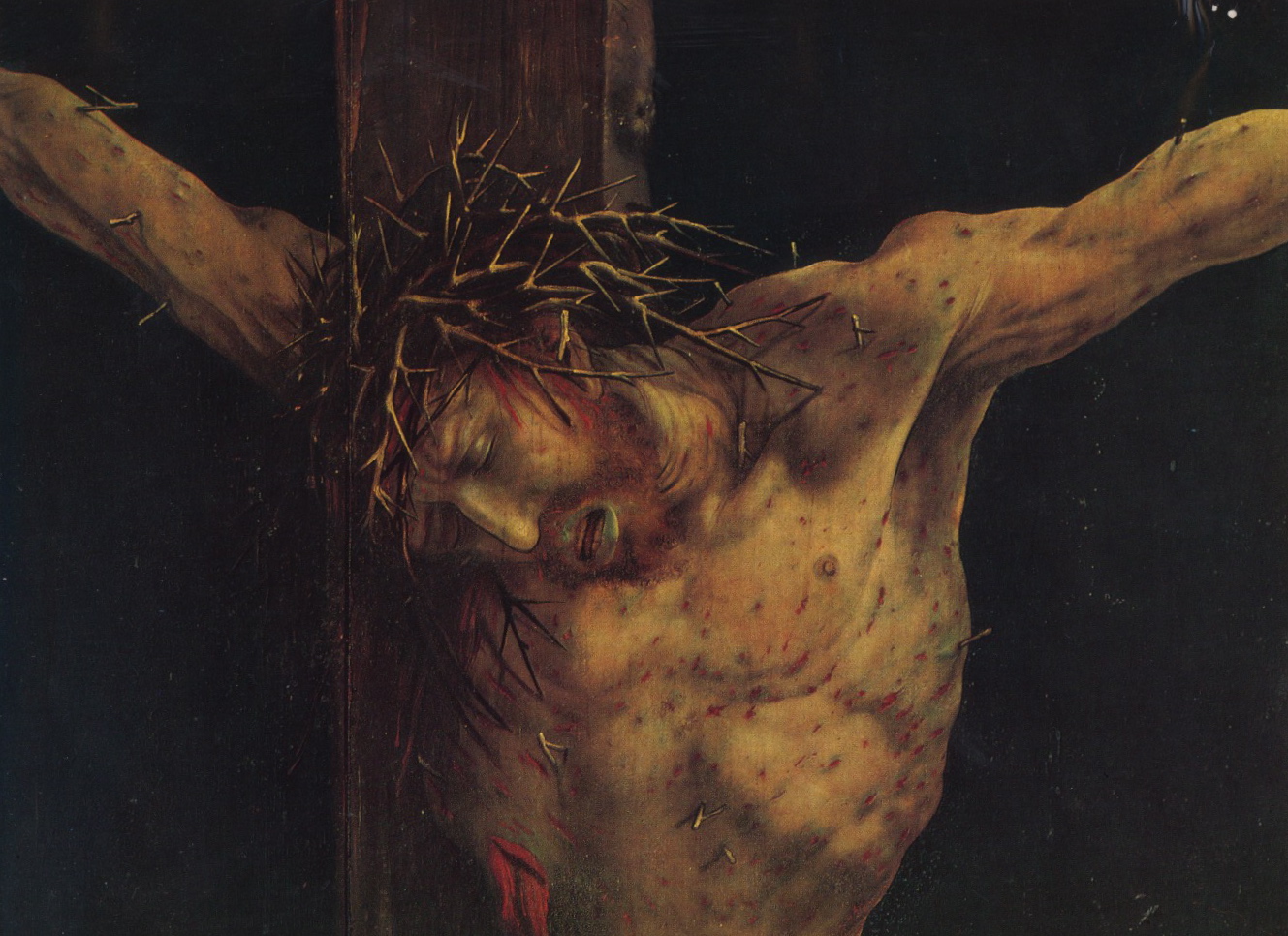

Mathias Grünewald, Crucifixion, Isenheim Altarpiece, c.1512/15

Mathias Grünewald, Crucifixion, Isenheim Altarpiece, c.1512/15

Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar

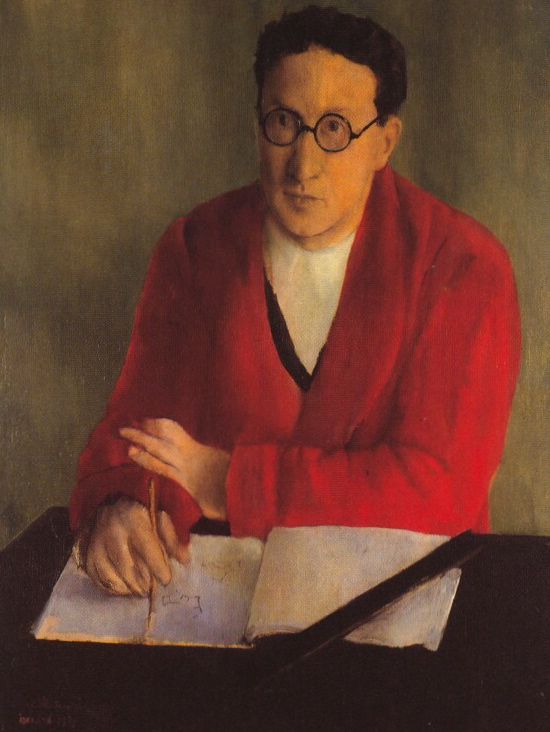

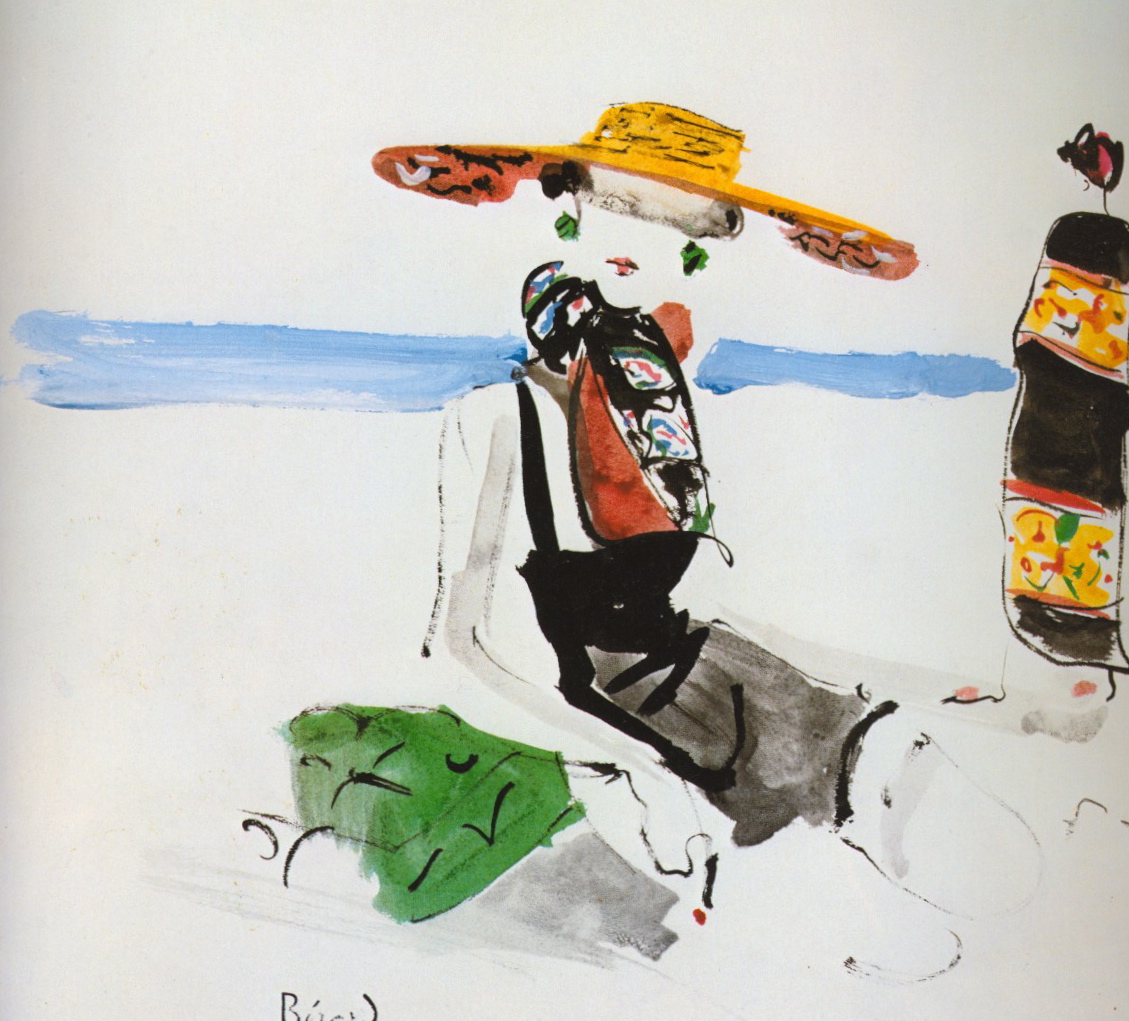

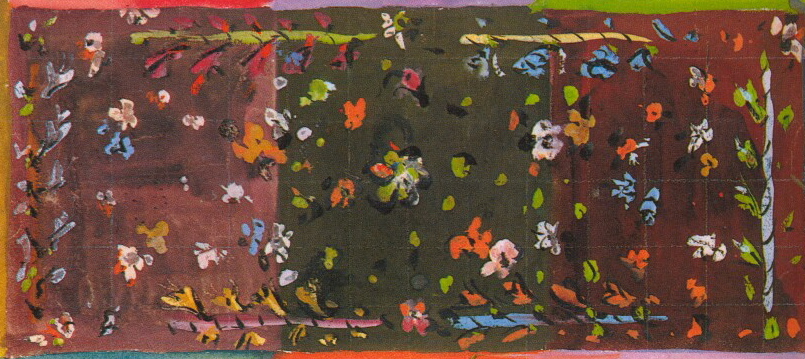

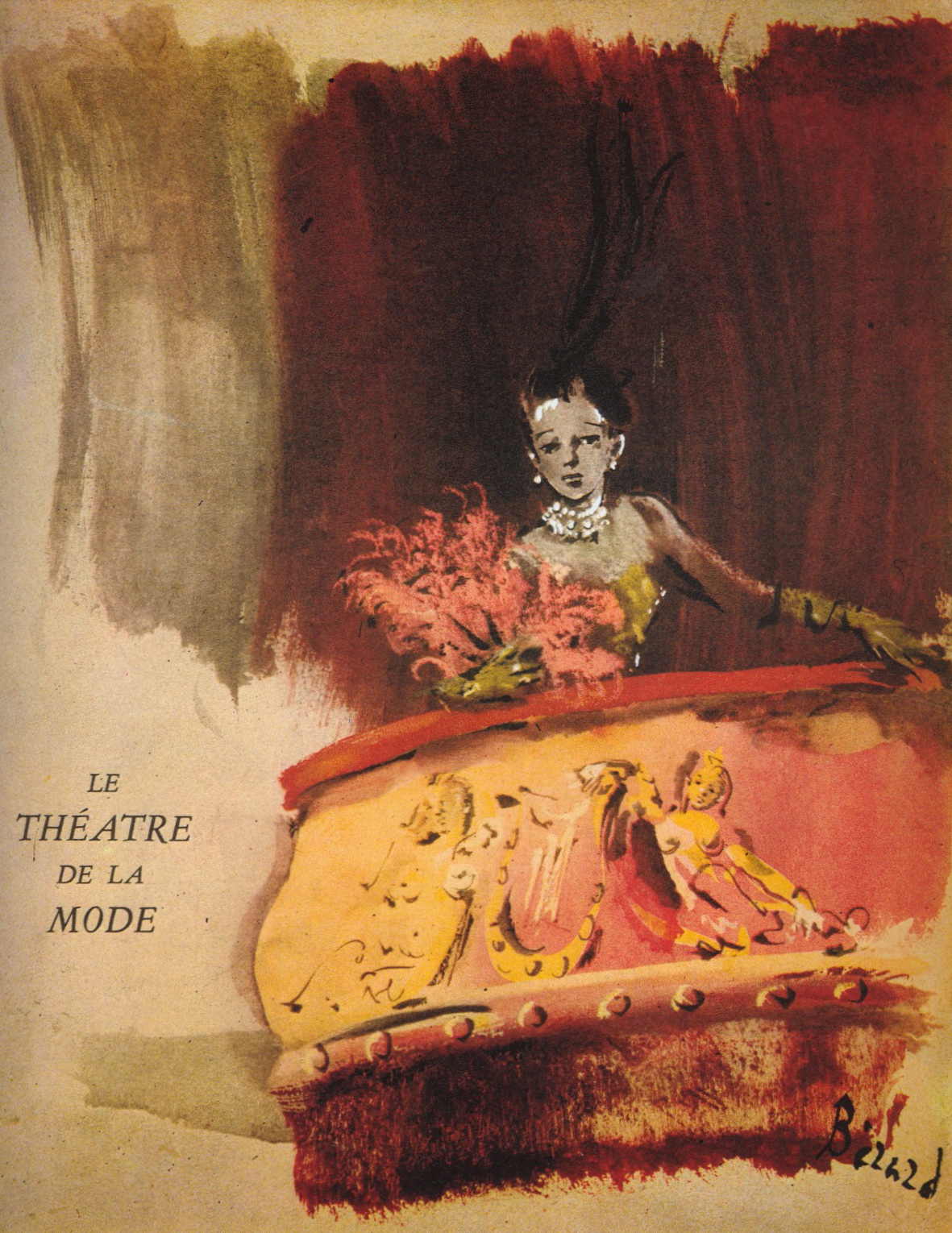

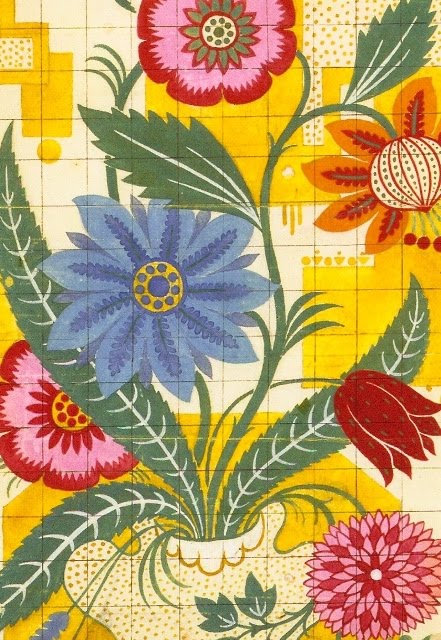

I’ve been thinking lately about the transformative power of art and its relevance in our troubled world. In medieval times, through its connection to the church, art held a more central place in people’s lives, as it sought to enlighten, instruct and relieve suffering.

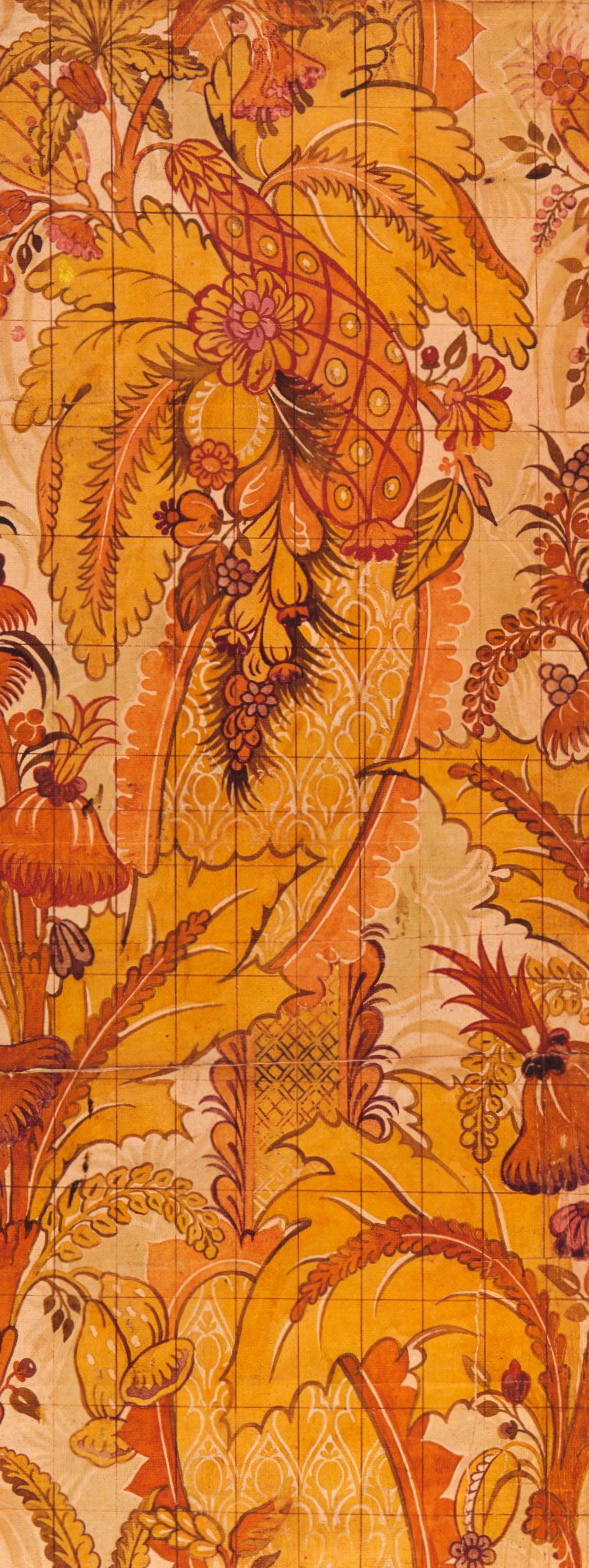

This brought to mind the Isenheim Altarpiece by German painter Mathias Grünewald (c. 1475-1528). The Isenheim Altarpiece embodies the human condition laid bare—from the extremes of catastrophic darkness to the rapture of resurrection and eternal life. The graceful, linear quality of the drawing and the vibrant, expressionist use of color would be enough to set this work apart—but Grünewald’s individualistic iconography and the intense emotional impact of the Isenheim Altarpiece make it completely unique.

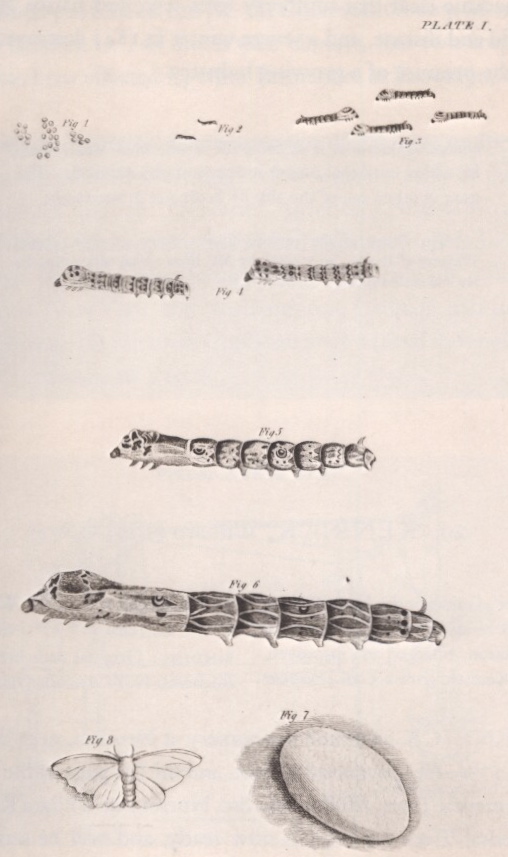

There is also another aspect of the Isenheim Altarpiece which intensifies its powerful spiritual presence—it was commissioned by the monks of a medieval hospital in the tiny hamlet of Isenheim to help lessen the suffering of their patients afflicted with a terrible skin disease called St. Anthony’s fire, or ergotism, which was caused by rye fungus. In a time before painkillers, the patients meditated on Christ’s intense suffering and resurrection to help them cope with their own agonies.

Crucifixion: Mary, John and Mary Magdalene (detail)

Crucifixion: Mary, John and Mary Magdalene (detail)

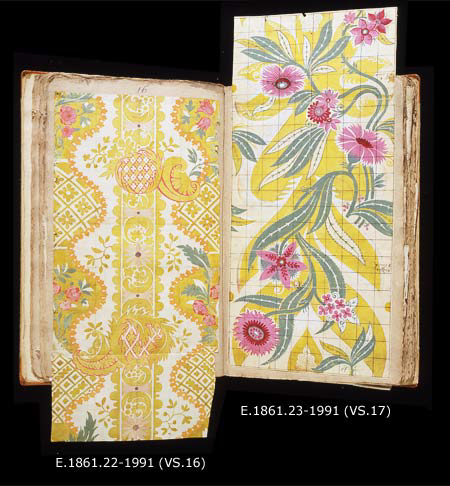

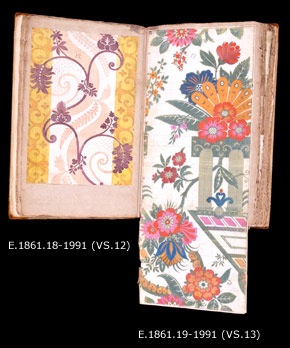

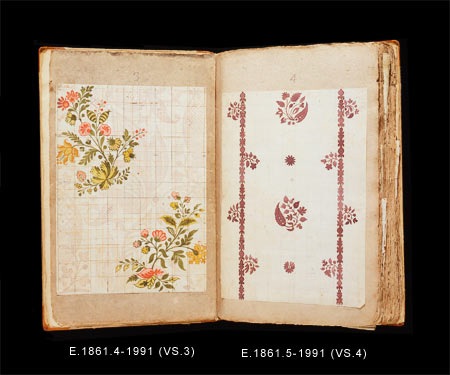

The Isenheim Altarpiece, painted on nine hinged panels, contains twelve images, including two sets of folding wings. It can be viewed in three ways. In its closed position—the way it would have been viewed originally on weekdays at the hospital—the central panel shows the Crucifixion, with side panels of St. Anthony and St. Sebastian. The second view shows the Annunciation, the Angelic Concert, the Madonna and Child and the Resurrection. In the third view, a pre-existing carved and gilded wooden altarpiece is flanked by Grünewald’s paintings of the Temptation of St. Anthony and the Meeting with Anthony and Paul.

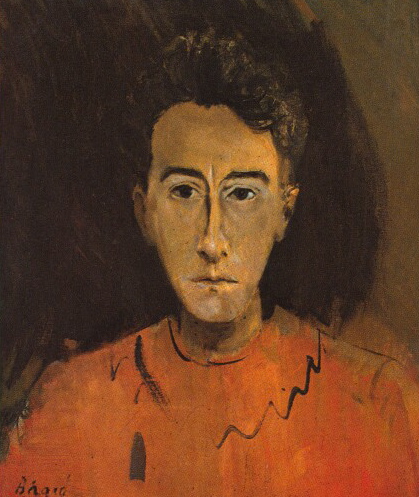

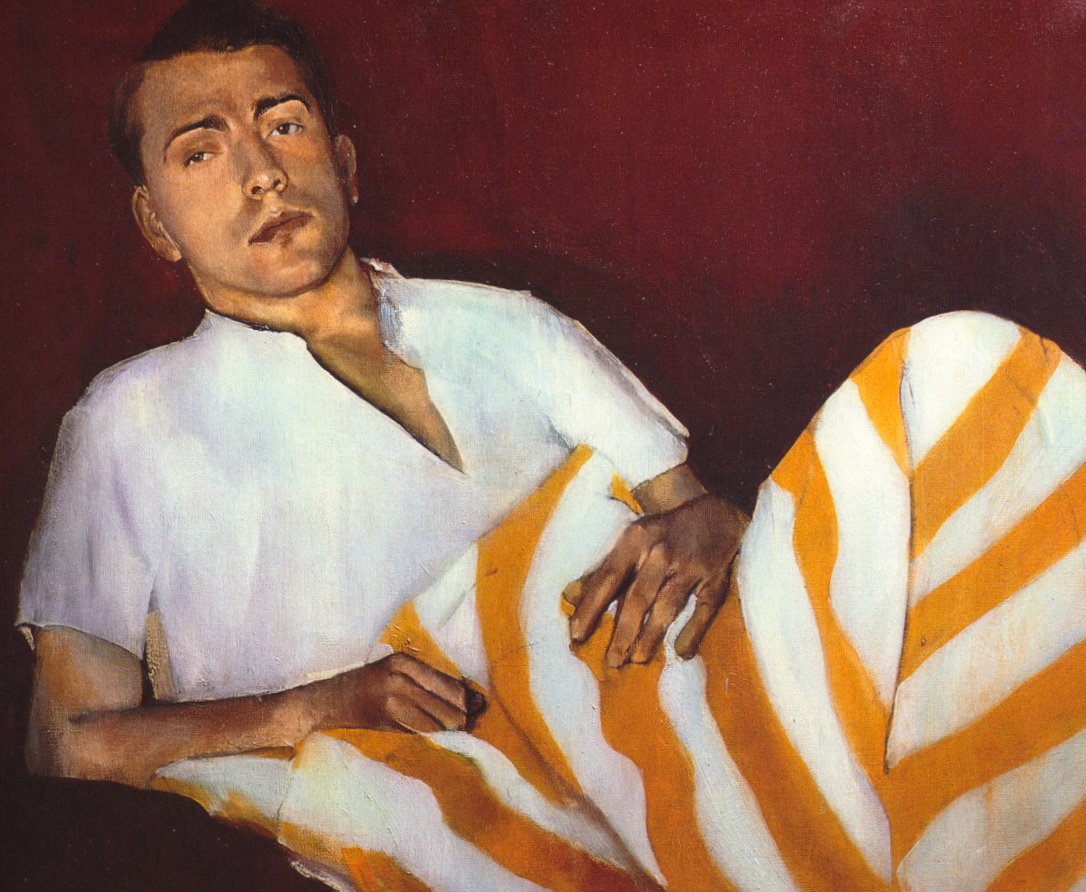

As the panels of the altarpiece were unfolded, the enormous scope of the intense, riveting drama was revealed. Grünewald’s image of the crucified Christ is imbued with a visceral and emotional intensity. Christ, his skin a grayish green, covered with wounds—has clearly writhed in agony, his limbs twisted, his hands distorted, his head with its crown of thorns hanging painfully on his chest. This is a portrait of a brutal, solitary death—the sense of immediacy, agony and isolation is palpable. By contrast, the resurrected Christ, surrounded by light, is a triumphant image of the rapture of eternal life.

Crucifixion: Head of Christ (detail)

Crucifixion: Head of Christ (detail)

Resurrection: Head of Christ (detail)

Resurrection: Head of Christ (detail)

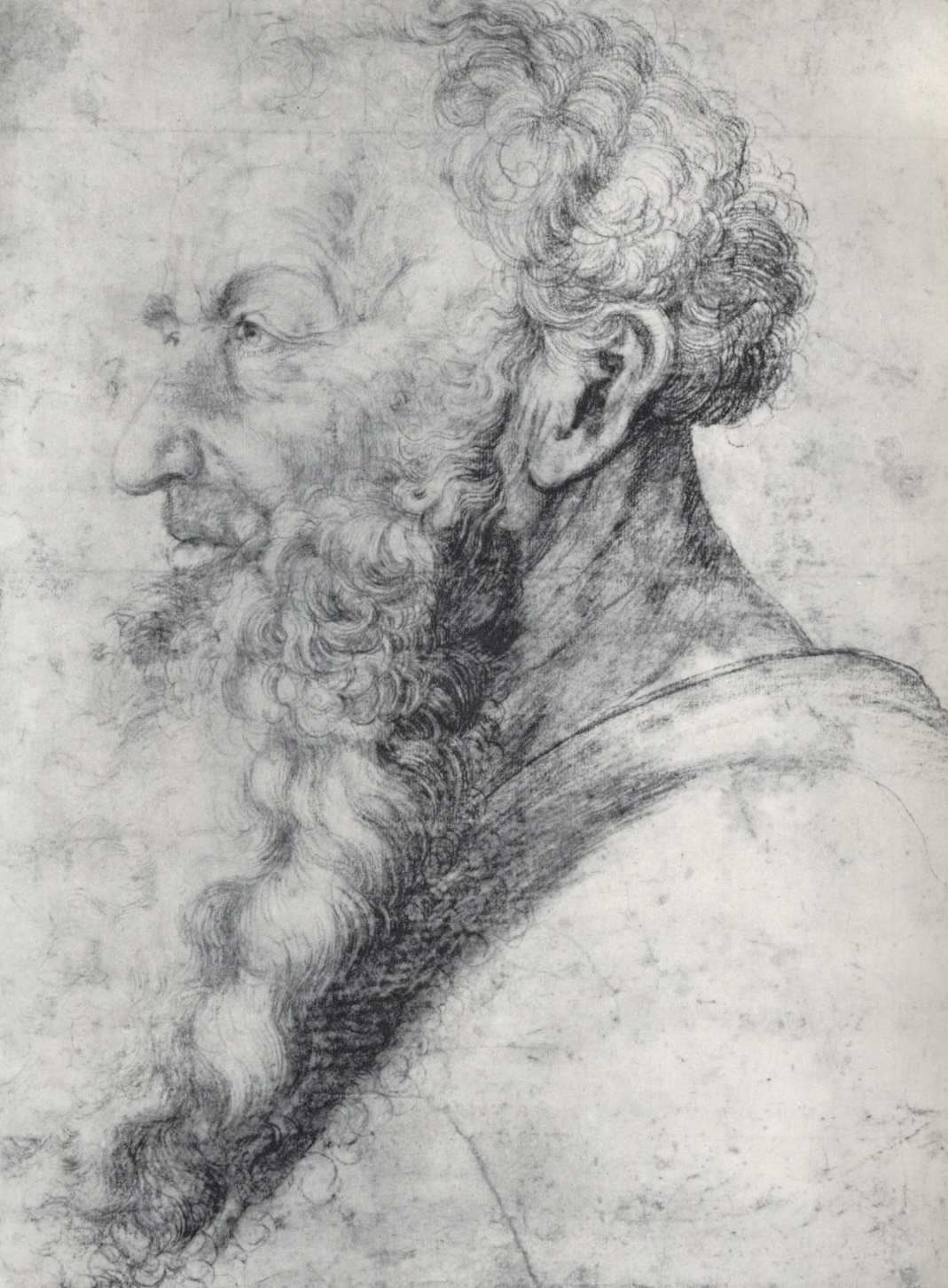

Mathias Grünewald’s real name was Mathis Gothardt Neihardt—the name Grünewald was mistakenly attributed to him 150 years after his death. For a painter who was so well-thought of in his own time, remarkably little information about him has been passed down and few of his works survive—only about ten paintings (including multi-paneled altar pieces) and 35 drawings. All the work that remains is religious in nature. Unlike Albrecht Dürer and the other great German artists of the time, who excelled at woodcarving and other forms of print making, Grünewald only made paintings and drawings, which in itself is very unusual. So little was known about Grünewald, that until the 19th century, it was believed that the Isenheim Altarpiece was painted by Albrecht Dürer.

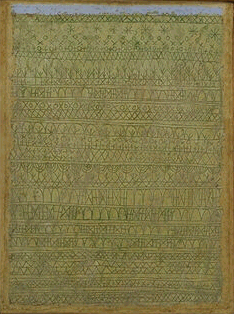

Study for Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512

Study for Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512

What we do know is that by 1509, Grünewald was court painter to the Archbishop of Mainz, and that he was commissioned to paint the Isenheim Altarpiece around 1512-15. Art historians disagree as to interpretations and influences—for example, one categorically states that Grünewald, because of his clear knowledge of Italian painting, must have traveled widely—another asserts he never left Germany. Personally, I don’t think the facts of Grünewald’s life can really do much to explain the expressive, luminous intensity of the work or how he pushed his artistic skill to the point where he could capture so powerfully the tension and emotion of this transformative work.

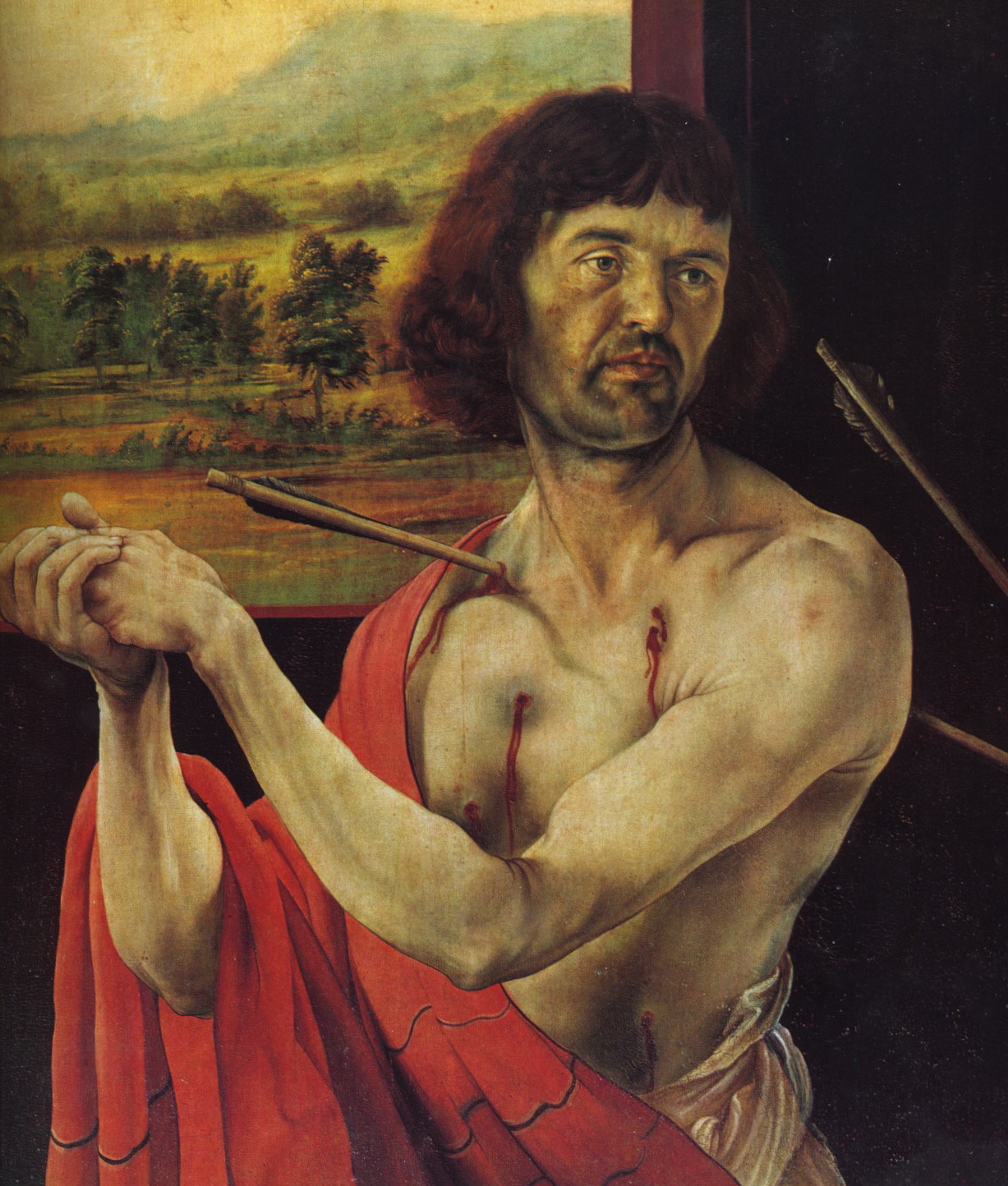

Crucifixion: St. Sebastian (detail)

Crucifixion: St. Sebastian (detail)

The complex and unusual iconography of the Isenheim Altarpiece is puzzling. The imagery in religious art of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance may seem mysterious to many of us today, but can be easily deciphered by art historians—the reason and background behind every element depicted can be traced, parsed and explained. Not so with Grünewald. Some of his iconography appears to be related to the work of the 14th century mystic, St Bridget of Sweden, whose Revelations was widely read in Germany at that time, but that does not explain all of the unusual visual references. It seems that Grünewald took an eclectic approach not only stylistically, but as regards subject matter as well.

Crucifixion: John the Baptist and the Lamb

Crucifixion: John the Baptist and the Lamb

Altarpieces were created for one purpose: to embody a specific aspect of generally recognized religious truth. In the process of spiritual meditation the barrier between the viewer and the artistic creation is broken. The Isenheim Altarpiece, in its intensity, tenderness and majesty is the power of this transformation made visible. Like Hieronymous Bosch, Grünewald infuses his work with a highly personal imagination that elicits a strong reaction from the viewer.

Monsters from the Temptation of St. Anthony panel

Monsters from the Temptation of St. Anthony panel

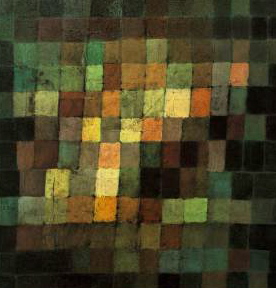

Grünewald clearly had a knowledge of Central European art from the late Gothic to the beginning of the 16th century, and incorporates elements from these various time periods in a highly original and independent way. There are links to Bosch and Netherlandish painting, as well as intimations of the naturalism of the Renaissance in Italy. Grünewald, on the cusp of the German Reformation, embodies aspects of both medieval and Renaissance art. Unlike the masters of the Italian Renaissance—whose work Grünewald may or may not have seen personally—Grünewald’s heavenly creatures are conjured from light, they are clearly not of this world. Painters of the Italian Renaissance incorporated spiritual beings into the known world. As an example, see the work of Michaelangelo who was painting the Sistine Chapel at the same time Grünewald was painting his altarpiece. In Grünewald, the supernatural world exists outside the human realm.

Grünewald’s masterpiece, forgotten for centuries, was rediscovered by a wider public following the horrors of World War I. At the outbreak of war, the Isenheim Altarpiece was moved from the Musée d’Unterlinden and sent for safe-keeping to Munich. After the war it was restored and exhibited for a time in the Alte Pinakothek before returning to Colmar. The Expressionists, then dominating the art scene in Germany, looked to Grünewald as their forerunner and to the Isenheim Altarpiece as the confirmation of their philosophy. The world, traumatized and overwhelmed by the death and destruction of the war, turned to the Isenheim Altarpiece for solace and inspiration.

Wider Connections

The Isenheim Altar: Suffering and Salvation in the Art of Grunewald by Gottfried Richter

Mathias Grünewald by Horst Ziermann

Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar