Seest thou the little winged fly, smaller than a grain of sand?

It has a heart like thee, a brain open to heaven and hell,

Withinside wondrous and expansive; its gates are not closed;

I hope thine are not. — William Blake

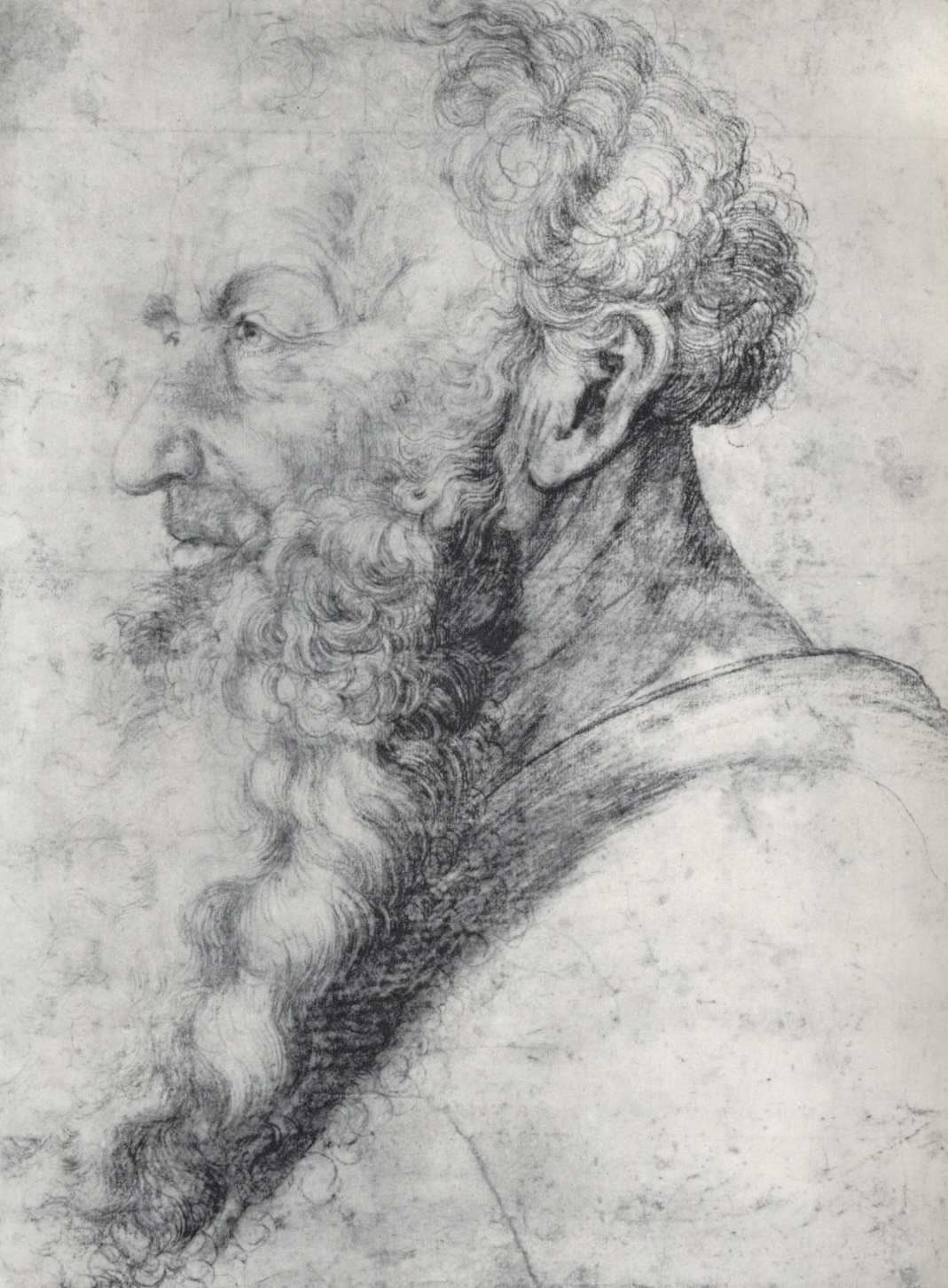

While rather squeamish about actual insects, I am entranced by images of insects in art—in still-life, natural history illustration and design. As Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) wrote:

It is indeed true that art is omnipresent in nature, and the true artist is he who can bring it out.

Albrecht Dürer, Stag Beetle, 1505

Albrecht Dürer, Stag Beetle, 1505

Watercolor on paper

Getty Museum

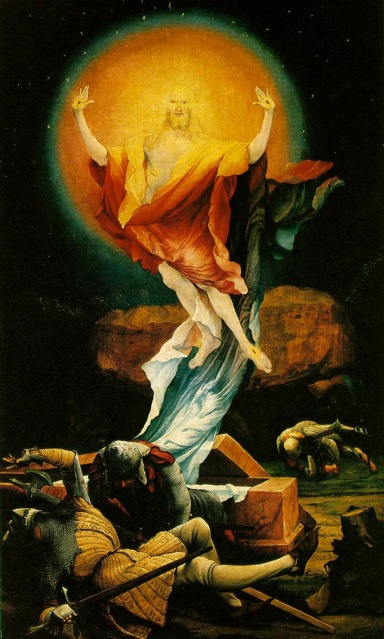

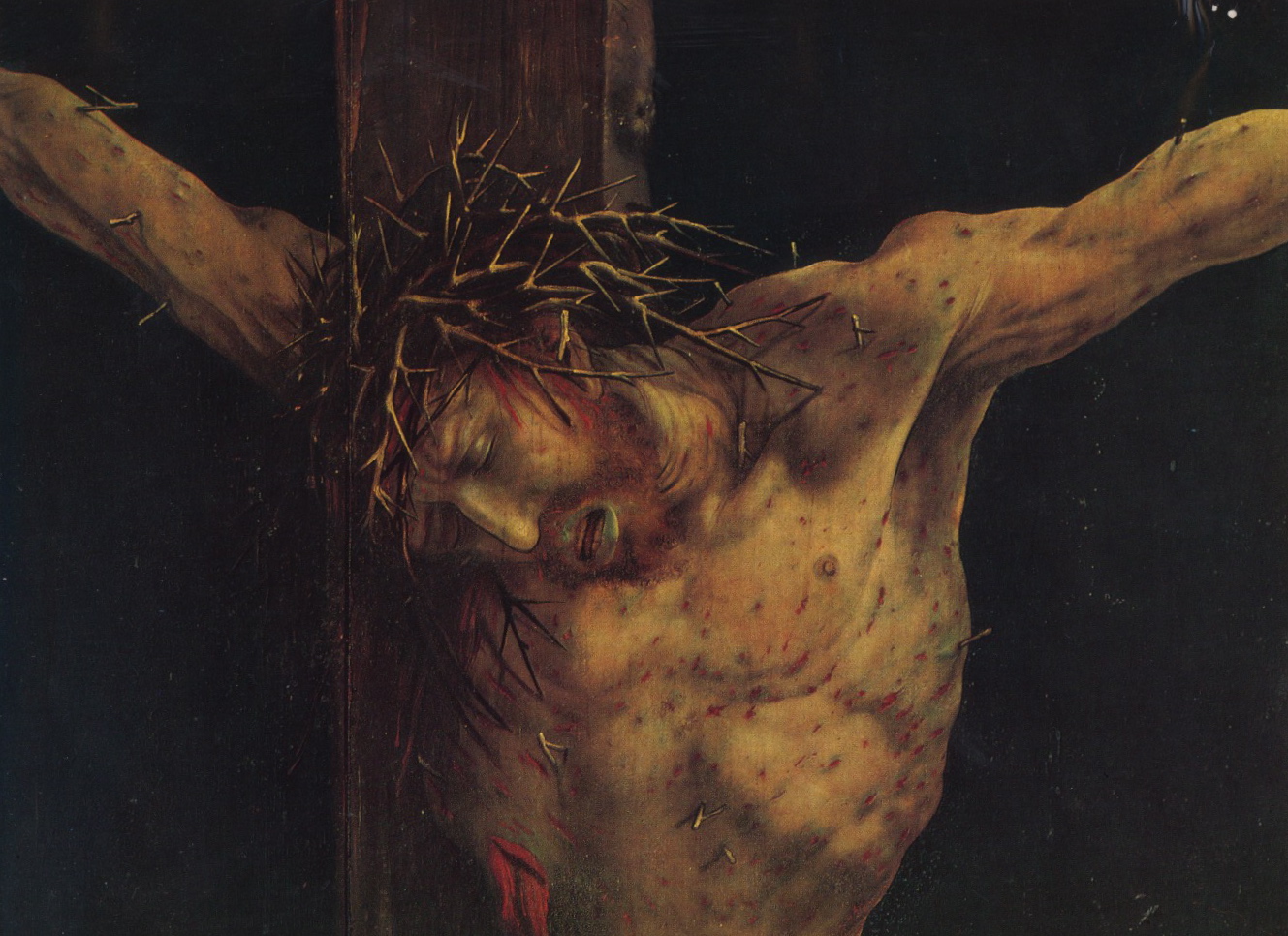

Dürer’s beautiful and dignified watercolor of a beetle is an early embodiment of the Renaissance respect for nature—Dürer was among the first of his contemporaries to give an insect center stage in a work of art. In antiquity, insects had been included in trompe l’oeil and memento mori paintings to demonstrate technical virtuosity and as symbols of evil and death, while butterflies represented transformation and resurrection. Insects in themselves were considered unworthy of consideration as subjects for painting.

By the 17th century, the obsession with natural history—and with insects as a miraculous part of the natural world—took precedence, and symbolism was left behind. Insects became subjects of study and fascination. Dürer, as always, ahead of his time, brings his masterful draughtsmanship to his watercolor, of a beetle—which he considered a finished work of art, not a study.

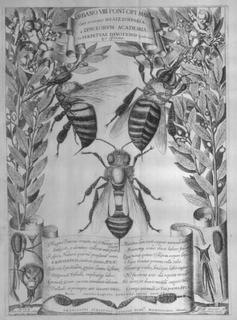

Francesco Stelluti‘s Melissographia, 1625, was the first scientific illustration done with the aid of a microscope and included three magnified views of a bee.

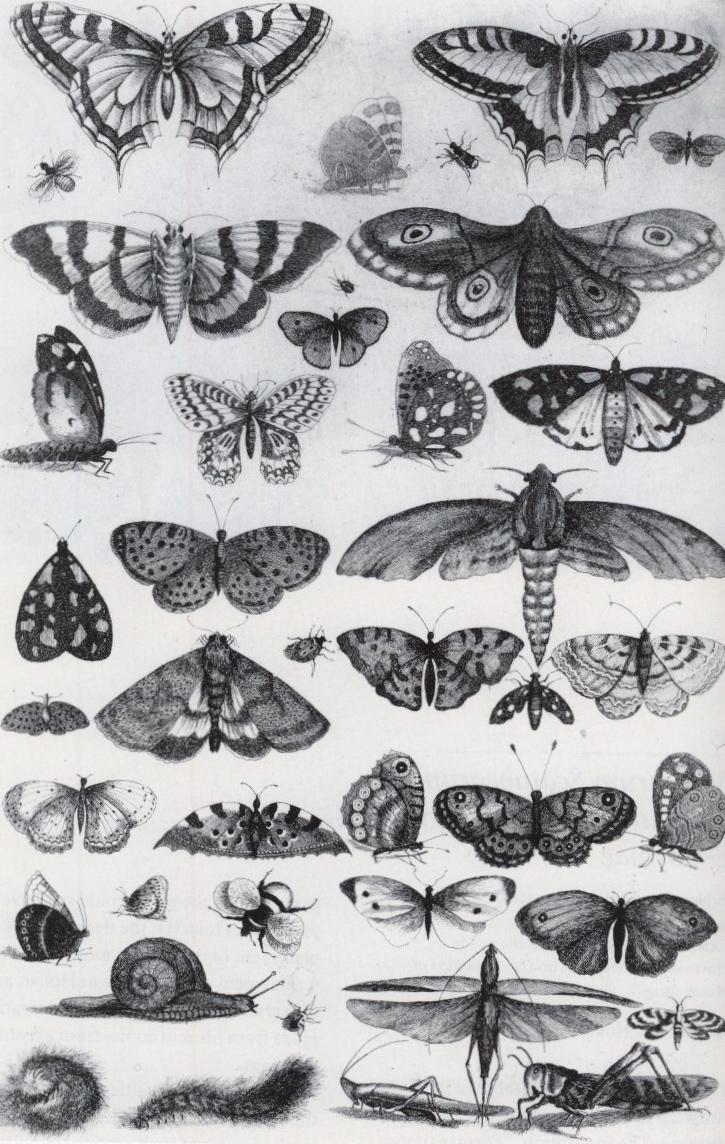

Wenceslaus Hollar, Forty-One Insects, Moths and Butterflies, 1646

Wenceslaus Hollar, Forty-One Insects, Moths and Butterflies, 1646

Etching from Muscarum Scarabeorum

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677) was a Czech-born master printmaker, whose natural history illustrations have an elegant sense of pattern and design. Cabinets of curiosity were the rage among collectors of the day, and assemblages such as this would part of the display. Hollar’s illustrations were likely influenced the engravings that Jacob Hoefnagel did from his father Georg Hoefnagel‘s original drawings.

Like many still-lifes of the period, Hoefnagel’s natural history studies often had a somber message. The title of his piece, below, which features flowers, a chrysalis, insects and a moth above a dead mouse reads: Nasci. Patri. Mori. (I am born. I suffer. I die.)

Jacob Hoefnagel, Archetypa Studiaque Patris Georgii Hoefnagel, 1592

Jacob Hoefnagel, Archetypa Studiaque Patris Georgii Hoefnagel, 1592

Engraving

Private collection, Switzerland

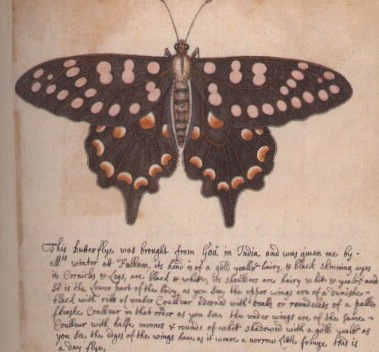

Alexander Marshal (c.1620-82) is famous for his beautifully drawn florilegium (flower-book) which he worked on for thirty years, until his death. This lovely butterfly study, above, was painted from one in the collection of naturalist, gardener and plant-hunter John Tradescant the Younger (1608-62) when Marshal was a guest at his house in London in 1641.

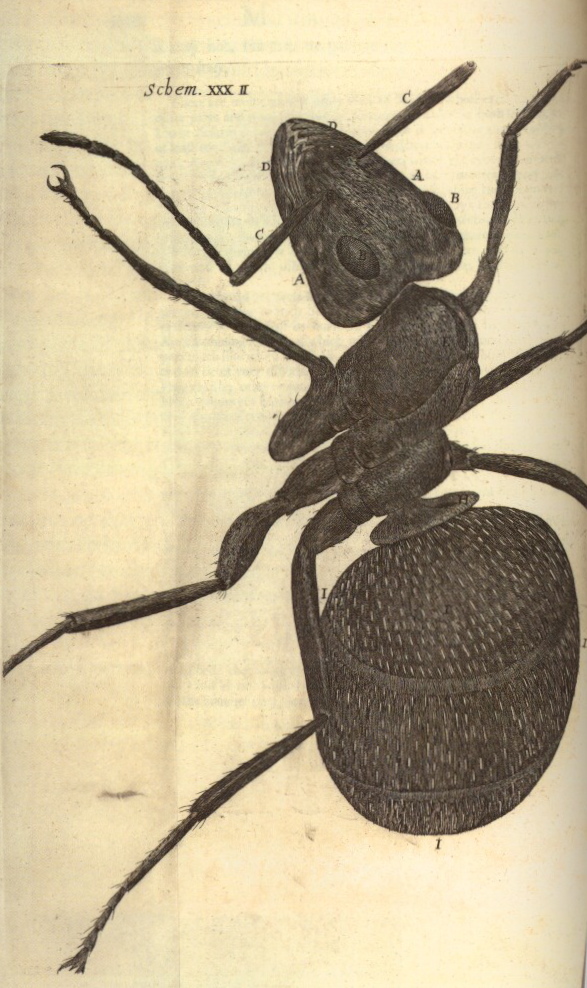

Robert Hooke, Ant, from Micrographia

Robert Hooke, Ant, from Micrographia

London, 1665

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

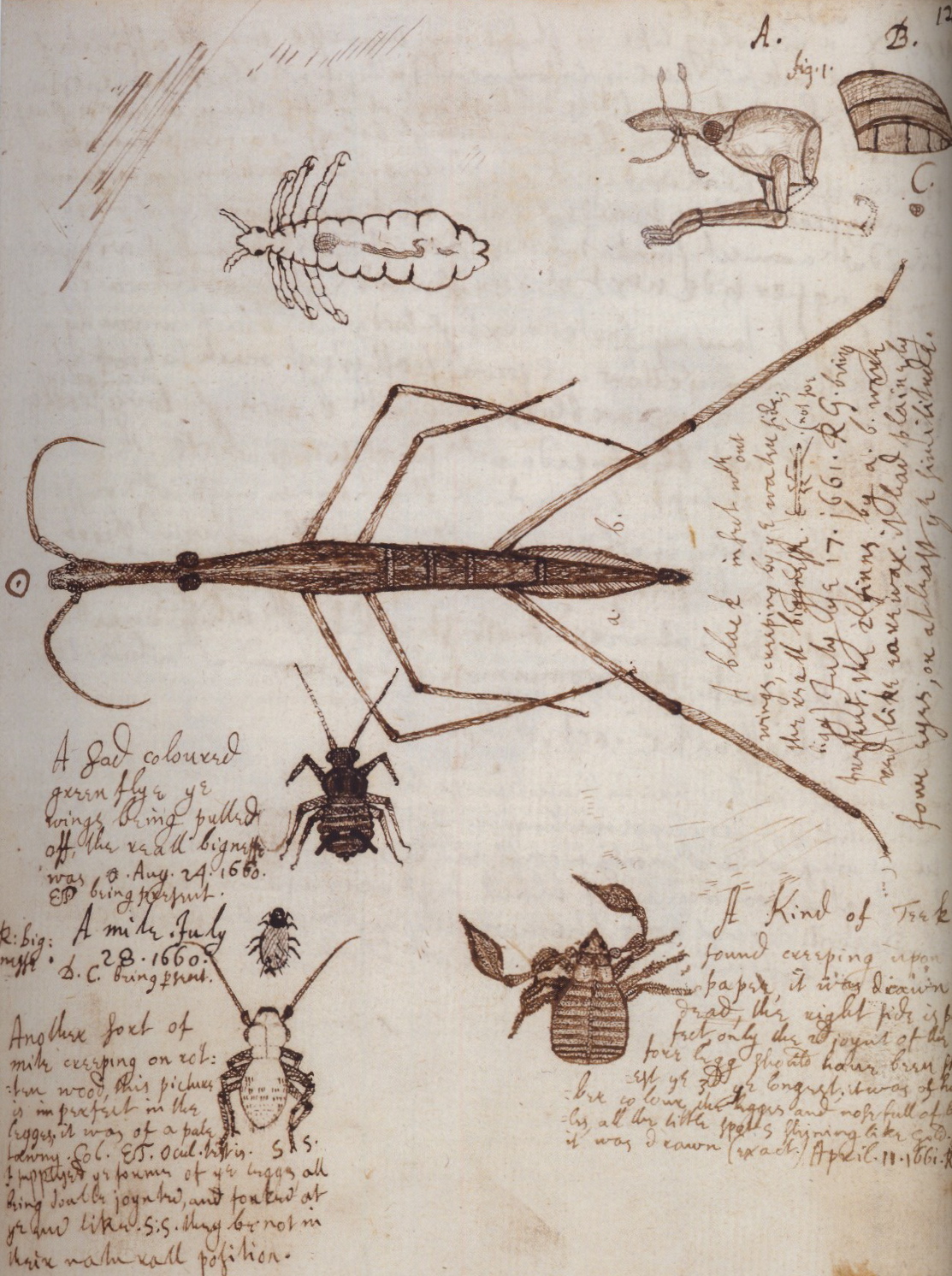

John Covel, Natural History and Commonplace Notebook, 1660-1713

John Covel, Natural History and Commonplace Notebook, 1660-1713

Drawings and notations by Robert Hooke and others

The British Library

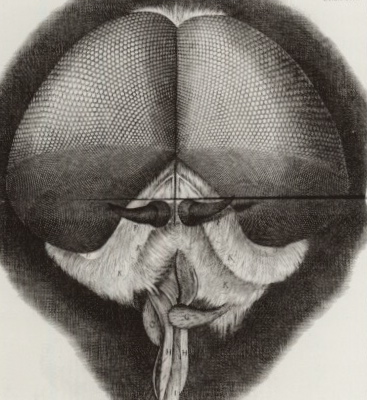

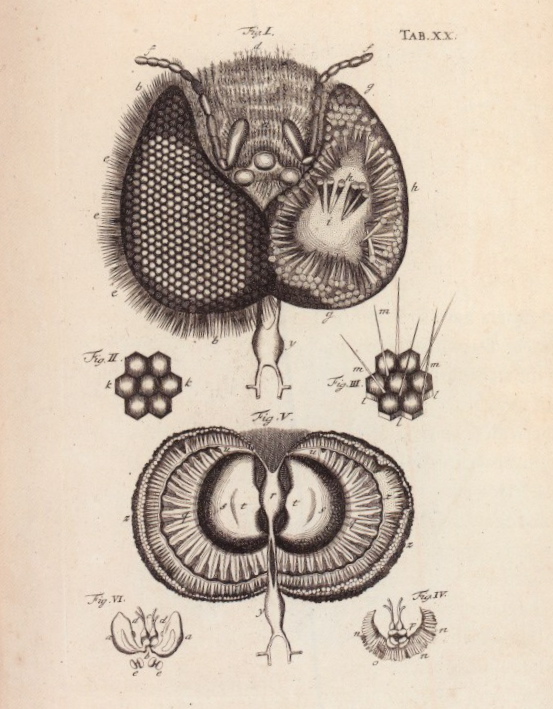

Robert Hooke, Eye of a Fly, from Micrographia, 1665

Robert Hooke, Eye of a Fly, from Micrographia, 1665

Engraving

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

The work of Robert Hooke (1635-1703) is extraordinary in its detail and accuracy. Hooke’s Micrographia is a landmark work in natural history illustration. It contains thirty-eight copperplate engravings, his subjects all brilliantly translated from his keen observations under the microscope to an authentic, beautifully rendered two-dimensional image.

Mark Catesby, Nightjar and mole cricket, detail, c. 1722-6

Mark Catesby, Nightjar and mole cricket, detail, c. 1722-6

Mark Catesby‘s (1682-1749) life work was his The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. His work really captures the life force of his subjects, and in this case, the predatory demands of survival.

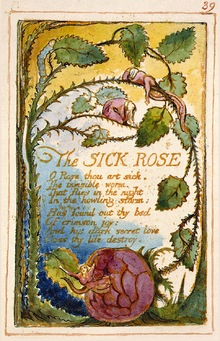

William Blake, The Sick Rose, from Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1789

William Blake, The Sick Rose, from Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1789

No artist captured the contradictory aspects of nature with more force and beauty than the great visionary Romantic poet, illustrator and printmaker, William Blake (1757-1827.) Blake, who described the human imagination as “the body of God,” and died singing and clapping his hands at the vision of heaven that awaited him—was nevertheless able to beautifully describe the dark, destructive aspect of nature.

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

Lens Aldous, Head of the Flea, c. 1838

Lens Aldous, Head of the Flea, c. 1838

Hand-colored lithograph, poster for Entomological Society of London

Hope Library, Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Two more impossibly detailed images of the heads of insects. Above, Lens Aldous was a specialist in micrographic illustration. The year this image was made, Charles Darwin was Vice-President of the Entomolgical Society of London.

Jan Swammerdam, The Book of Nature; Or, The History of Insects, 1758

Jan Swammerdam, The Book of Nature; Or, The History of Insects, 1758

Engraving

Cambridge University Library

The drawing, above, of the head of a male bee, is in a book from Charles Darwin’s personal library. Microscopic studies were extremely important to the development of Darwin’s theories about evolution.

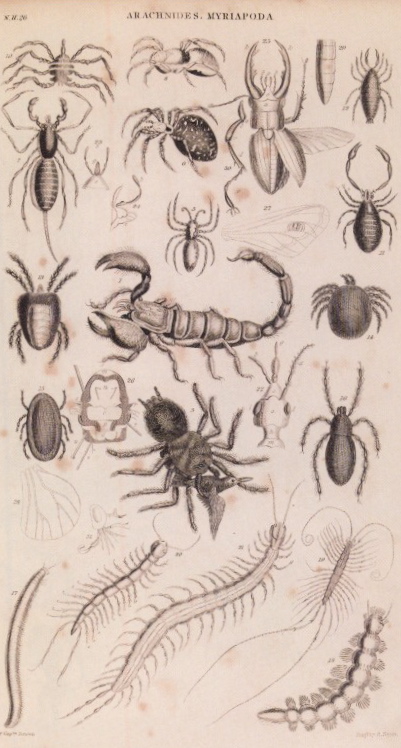

R. Scott, Arachnides, Myriapoda, c.1840

R. Scott, Arachnides, Myriapoda, c.1840

This illustration, above, is not just an inventory of types of spiders, it also shows the predatory nature of these creatures—note the bird in the grasp of the giant spider.

Jan van Kessel, Insects and Fruit, c. 1636-1679

Jan van Kessel, Insects and Fruit, c. 1636-1679

Oil on copper

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Jan van Kessel, Insects on a Stone Slab, c. 1660-70

Jan van Kessel, Insects on a Stone Slab, c. 1660-70

Oil on copper

Kunstmuseum, Basel

My favorite painter of insects is Jan van Kessel (1626-1679.) As with his bird tableaus, van Kessel created mini-universes teeming with life in his natural history scenes. His works are mostly small oil paintings on copper or wood. Often studies like these were made into prints for natural history collectors.

Justus Juncker, Pear with Insects, 1765

Justus Juncker, Pear with Insects, 1765

Oil on oakwood

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

There are many 17th century still-lifes in which insects do not have center stage but instead play a supporting role. This beautiful painting by Justus Juncker (1703-1767) presents the pear as a sculptural form—the dramatic lighting and its isolation on the pedestal gives it a mysterious and monumental presence. Again, there are intimations of mortality—the plinth is chipped and cracked, and the small tears in the skin of the fruit has attracted insects.

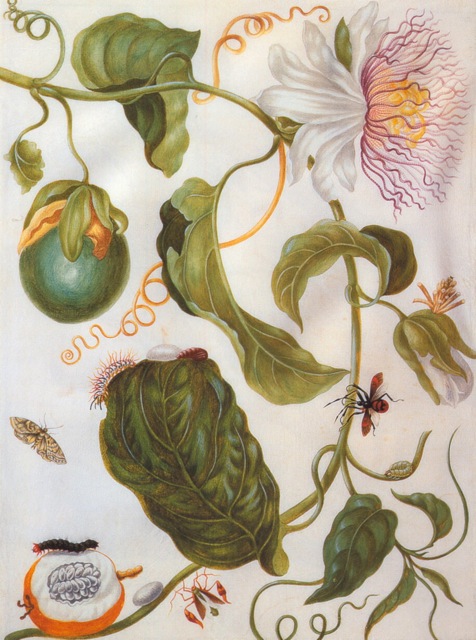

Maria Sibyla Merian, Branch of guava tree with leafcutter ants, army ants, pink-toed tarantulas, c. 1701-5

Maria Sibyla Merian, Branch of guava tree with leafcutter ants, army ants, pink-toed tarantulas, c. 1701-5

I can think of no more intriguing examples of botanical art than the work of artist and naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717.) Merian began her entymological studies at thirteen, when she embarked on a study of flies, spiders and caterpillars. In 1705, Merian published her stunning Metamorphosis, a folio of 60 engraved plates of the life cycle of the butterflies and insects of Surinam, where she’d been on expedition from 1699-1701. I love the way Merian plays with scale, conflates species and creates drama with her lively and energetic compositions.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Passion flower plant and flat-legged bug, c. 1701-5

Maria Sibylla Merian, Passion flower plant and flat-legged bug, c. 1701-5

Maria Sibylla Merian, Vine branch and black grapes, with moth, caterpillar and chrysalis of gaudy sphinx, 1701-5

Maria Sibylla Merian, Vine branch and black grapes, with moth, caterpillar and chrysalis of gaudy sphinx, 1701-5

Insects also fired the imagination of Victorian fairy painters. Their work was full of creatures that were half-human/half-insect—and elves and fairies ride around on the backs of butterflies and birds. This costume sketch, below, is from Charles Kean‘s production of a Midsummer Night’s Dream which was produced at Princess’s Theatre, London, in 1856. Shakespeare’s play was an abiding theme in paintings of this genre.

Joseph Noël Paton, The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania, detail, 1849

Joseph Noël Paton, The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania, detail, 1849

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Scotland Edinburgh

John Anster Fitzgerald, Faeries with Birds, detail

John Anster Fitzgerald, Faeries with Birds, detail

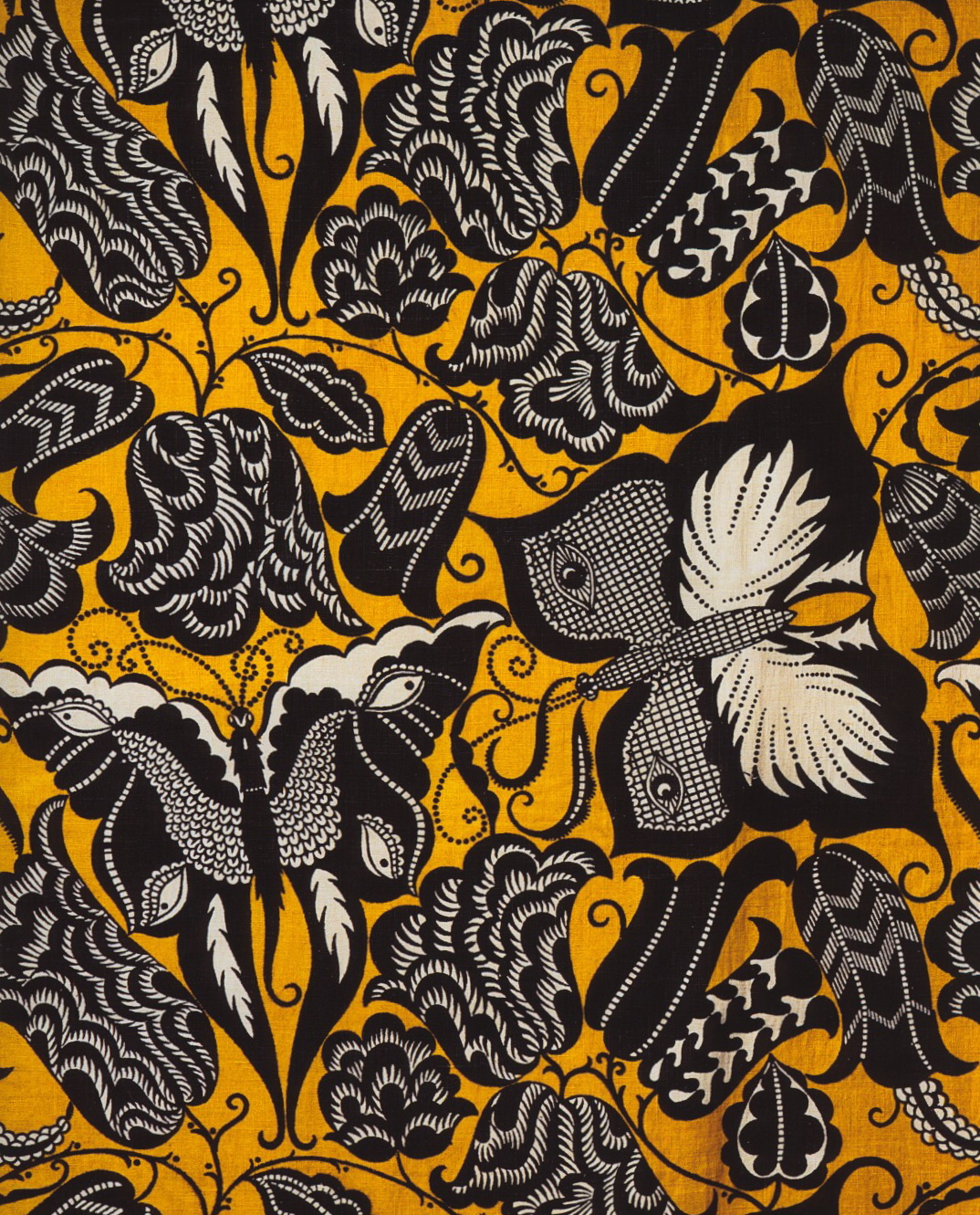

In the area of design, textile designers have also made good use of insect imagery, for example, this charming and colorful insect design from France, c. 1810.

And, below, Dagobert Peche‘s vibrant Swallowtail design done for the Weiner Werkstätte c. 1913.

In 1926, master of French Art Deco design, Emile-Alain Seguy painted this beautiful pattern of butterflies and roses.

Seguy was perhaps most famous for his amazing series, Insectes, done in collotype with pouchoir.

Contemporary artist Jennifer Angus creates large-scale installations made from petrified insects that are reminiscent of Victorian cabinets of curiosities. Angus’ work, with its kaleidescopic imagery, is an amalgam of science and art. It is highly decorative but is also meant to educate the viewer about the important role of insects in our environment.

Jennifer Angus, Grammar of Ornament, 2004

Jennifer Angus, Grammar of Ornament, 2004

Installation, University of Wisconsin

Angus gets most of her bugs through harvesters in Southeast Asia, and recycles insects from piece to piece. A link to a podcast about Angus’ 2008 show at the Newark Museum, Insecta Fantasia, is below:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bTF6-AlcS4A]

Before humans drew plants, landscapes or images of themselves—they drew animals and insects. The fascination with the natural world and the creatures that share our planet is ancient and enduring. I am grateful to the artists whose sustained intense observation and attention to detail have brought these creatures to life on the page.

The busy bee has no time for sorrow.

The hours of folly are measur’d by the clock; but of wisdom,

No clock can measure…

—from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell by William Blake