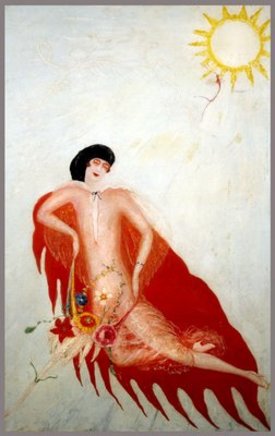

Florine Stettheimer, c 1917-20

Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library

It is often said that Florine Stettheimer, an early-Modernist painter of extreme originality and wit, lived a charmed life. Born to a wealthy German-Jewish family in New York in 1871, she was one of five children. Early on, her father left the family; she and her siblings grew up mostly in Europe. Stettheimer returned to New York in the early 1890s to study at the Art Student’s League, after which she returned to Europe, where she traveled extensively and studied art in Paris and Munich. In 1914, on the eve of World War I, she returned to New York with her mother and two sisters—Carrie and Ettie—and the family settled into an apartment in Alwyn Court on West 58th Street, near Carnegie Hall. There, Stettheimer and her sisters established a legendary salon that was frequented by many of the most important creative people of the time—among them, Marcel Duchamp, Carl Van Vechten, Gaston Lachaise, Sherwood Anderson, Edie Nedelman, Virgil Thompson, Edgar Varese, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Steiglitz and the art critic Henry McBride.

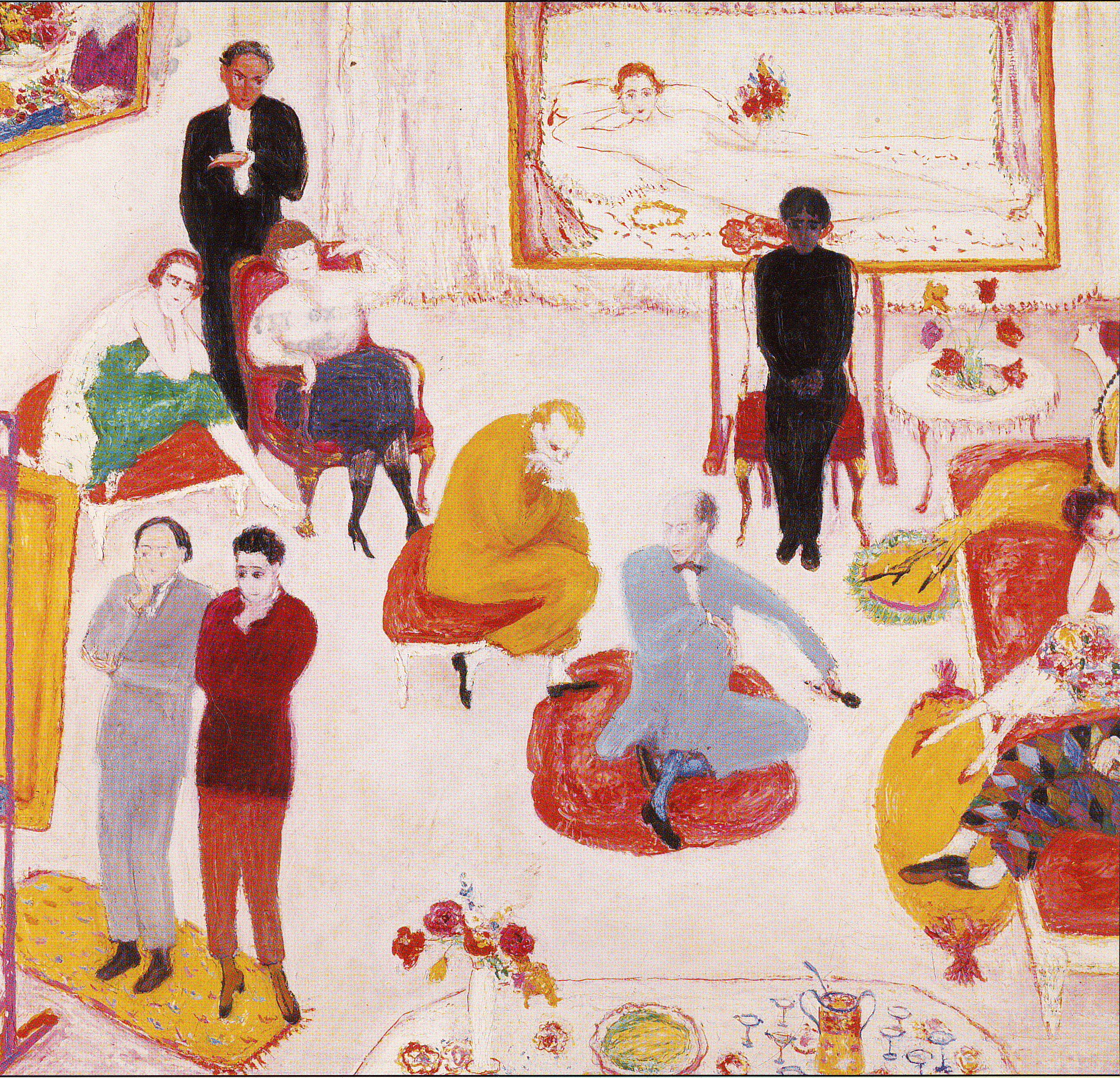

Florine Stettheimer, Soiree, 1917-1919

Florine Stettheimer, Soiree, 1917-1919

Beinecke Library, Yale University

In 1916 the Knoedler Gallery in New York mounted a show of Stettheimer’s work which was a critical and financial disaster. This disappointment, while keenly felt, fortunately pushed Stettheimer to leave behind her tentative, somewhat derivative post-Impressionist style and move on to what was to become her mature work. However, after this disappointment, she mostly showed her work in small group shows or privately at her studio, rarely showing her paintings publicly and refusing to put any of her work up for sale. Before her death in 1944 at the age of 73, Stettheimer asked that her family destroy all of her paintings—fortunately, they did not. In 1946, two years after her death, and at the suggestion of one of her closest friends, Marcel Duchamp, a retrospective of her work was mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The show was curated by another friend, art critic Henry McBride. Although critics of the time acknowledged her as as a very important Modernist painter of the early 20th century, and she had the respect and admiration of many of her peers, her paintings then disappeared from view until 1995, when they were exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This show, Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica, included early work, her most fully-realized post-1915 pieces as well as her theater and costume designs, dolls and collages.

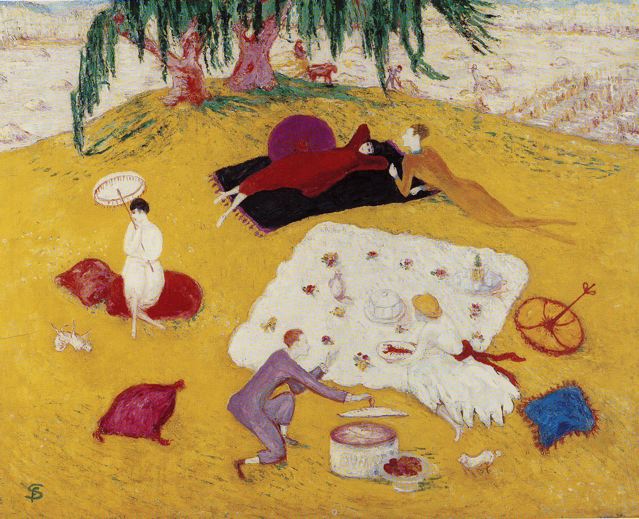

Florine Stettheimer, Picnic at Bedford Hills, 1918

Florine Stettheimer, Picnic at Bedford Hills, 1918

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

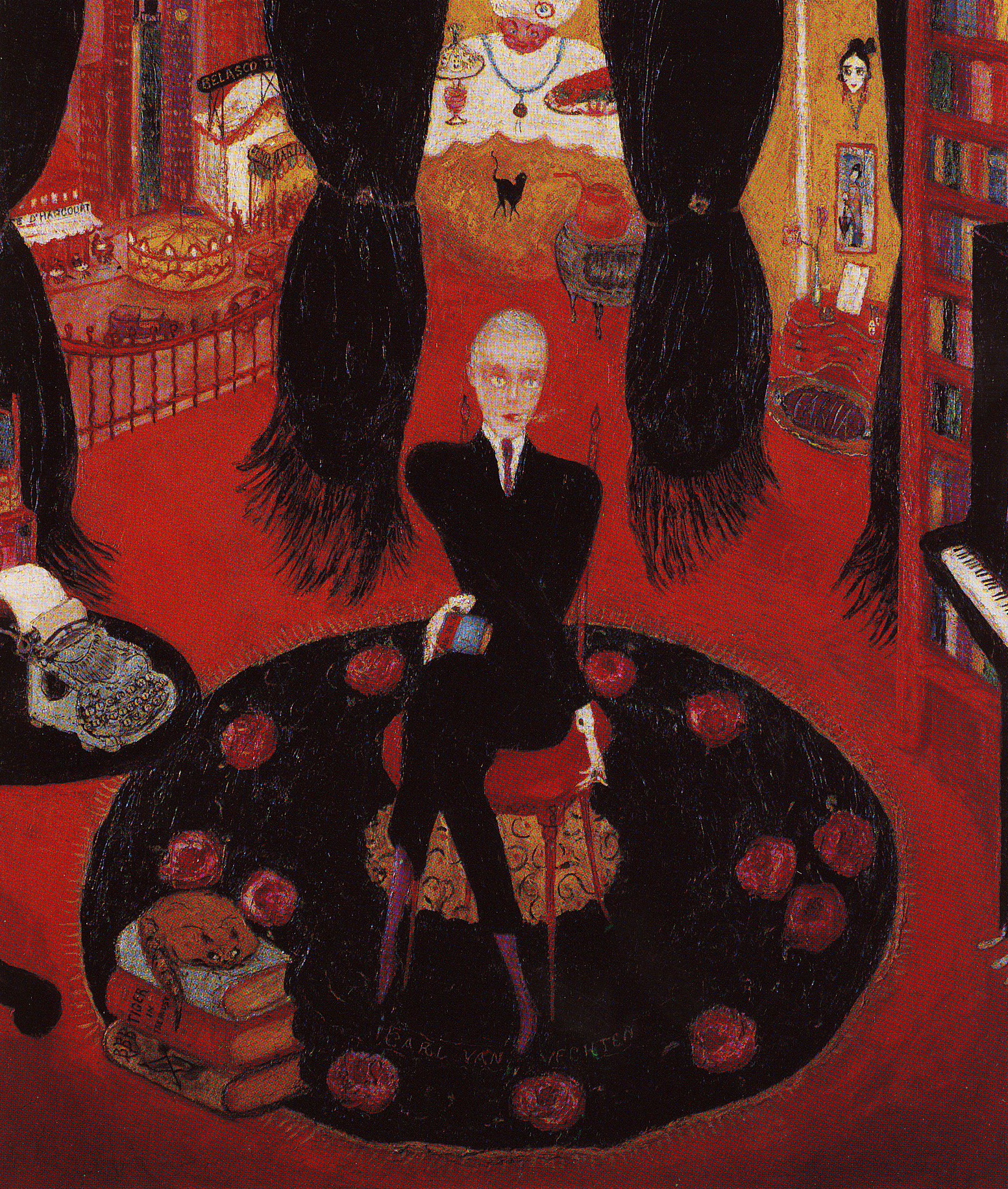

Stettheimer’s paintings are deeply personal—her main subject matter was her family and friends and the rather dreamy world of pleasure they inhabited. In her dazzling and eccentric paintings, with their bold color and openly feminine sensibility, Stettheimer created a unique synthesis of things she studied and loved—one catches glimpses of medieval portraiture, Persian miniatures, Brueghel, early Renaissance painting, Velasquez, children’s art, theater design, Matisse, Surrealism, Symbolism, folk art, fashion illustration, decorative art and interior design. She combines high/low elements in vivid constructions that depict scenes in a non-sequential, dream-like way—she played with perspective and her people and objects often float languidly through a complex universe of multiple narratives that have an allegorical quality. Her use of color was extraordinary, very American, and a complete break with the naturalistic earth tones of European painting. She favored deep reds, blacks, vivid pinks, vibrant blues and deep yellows, often in contrast to strong whites or soft pastels. Her portraits of family and friends in sitting rooms, salons, and summer houses; at picnics, luncheons and soirees—emphasized and immortalized their individual talents and interests. A good example of this is her portrait, below, of the writer Carl Van Vechten, who sits in the center of the painting, surrounded by his cats, books, typewriter and myriad artifacts from his life and work.

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Carl Van Vechten, 1922

Beinecke Library, Yale University

And this portrait of her sister Effie, in which Henry McBride described her as looking “…wide-eyed, for the mystery of life…as happy a blend of her worldliness and spirituality as any psychiatrist could ask for.”

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of My Sister, Ettie Stettheimer, 1923

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of My Sister, Ettie Stettheimer, 1923

Columbia University

While Stettheimer made the decision to only show her work privately during her lifetime, she also suffered from the neglect and was resentful of the lack of recognition. Like many women artists, Stettheimer’s personal life has long overshadowed her art. Her work has been vilified as being too feminine, although, as Barbara Bloemink points out, in the prologue to her excellent book, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer, “it is difficult to imagine anyone criticizing a work of art as being too masculine.” There was also another obstacle to recognition by the art establishment–she made them uncomfortable. The art world is very inhospitable to independent artists whose work is idiosyncratic and who are neither part of any school nor followers of any group. In his 1996 article on Stettheimer in Art in America, Trevor Winkfield writes: “You can paint anything in New York, runs a well-known truism, as long as three other people are doing the same thing.”

Florine Stettheimer, Heat, 1919

Florine Stettheimer, Heat, 1919

The Brooklyn Museum

Stettheimer also had an abiding interest in costume and set design. When she lived in Paris, she fell in love with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which inspired her to write a story for a ballet, Orphee des Quat’z-Arts, in 1912. The ballet was never produced, but Stettheimer designed costumes and built some model sets—the Museum of Modern Art has 44 of the sketches (see below) in their collection, but not on view. In 1934, Stettheimer designed sets and costumes for the Gertrude Stein/Virgil Thomson opera,Four Saints in Three Acts. Very avant-garde for the day, she fashioned the sets from tinsel, cellophane and lace, apparently to great effect when lit to her specifications.

Florine Stettheimer, Euridice and Her Snake, Two Tango Dancers and St. Francis

Florine Stettheimer, Euridice and Her Snake, Two Tango Dancers and St. Francis

design for Orphee des Quat’z Arts, 1912

Gouache, watercolor, metallic paint and pencil on paper

In 1935, Stettheimer’s mother died, and Florine surprised everyone by moving into her studio in the Beaux Arts Building at 8 West 40th Street—living by herself, for the first time, at the age of sixty-four. The success and acclaim garnered from Four Saints, and her newly found independence, increased her self-confidence and spurred her on to a new phase of her work in which she re-worked old themes with a new sense of clarity and purpose.

Florine Stettheimer, Family Portrait Number 2, 1933

Florine Stettheimer, Family Portrait Number 2, 1933

Museum of Modern Art, New York

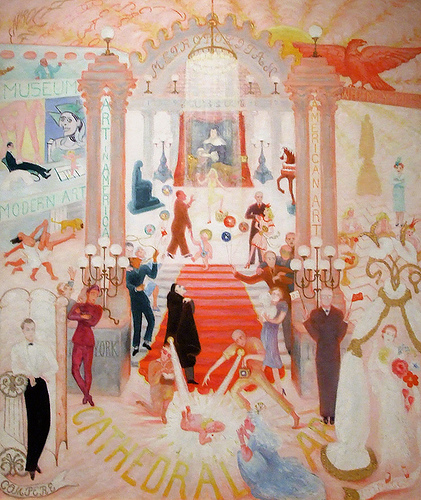

Her last painting, unfinished at her death, The Cathedrals of Art, is a multi-narrative work, somewhat reminiscent of the structure of early Renaissance painting, that satirizes the power-brokering and competitiveness of the New York art world. The art critic Hilton Kramer later described it as “comic opera…the whole scene is one of shameless hustling and posturing. It is a prophetic as well as a delightful painting.”

Florine Stettheimer, Cathedrals of Art, 1943-44

Florine Stettheimer, Cathedrals of Art, 1943-44

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Stettheimer was a dedicated, accomplished artist who was full of contradictions–she wanted to both avoid the critical spotlight and achieve recognition for her work. In her paintings and poetry she created and re-created the narrative of her life. In her imagery, narratives collide and split, time is erased and reordered. Perhaps this poem, published privately and posthumously in Crystal Flowers, 1949, gives us a glimpse into her elusive persona:

Occasionally

A human being

Saw my light

Rushed in

Got singed

Got scared

Rushed out

Called fire

Or it happened

That he tried

To subdue it

Or it happened

That he tried to extinguish it

Never did a friend

Enjoy it

The way it was.

So I learned to

Turn it low

Turn it out

When I meet a

stranger—

Out of courtesy

I turn on a soft

Pink light

Which is found

modest

Even charming.

it is protection

Against wear

and tears…

And when

I am rid of

The Always-to-be-

Stranger

I turn on my light

And become

myself.

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Myself, 1923

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Myself, 1923

Collection, Columbia University, New York