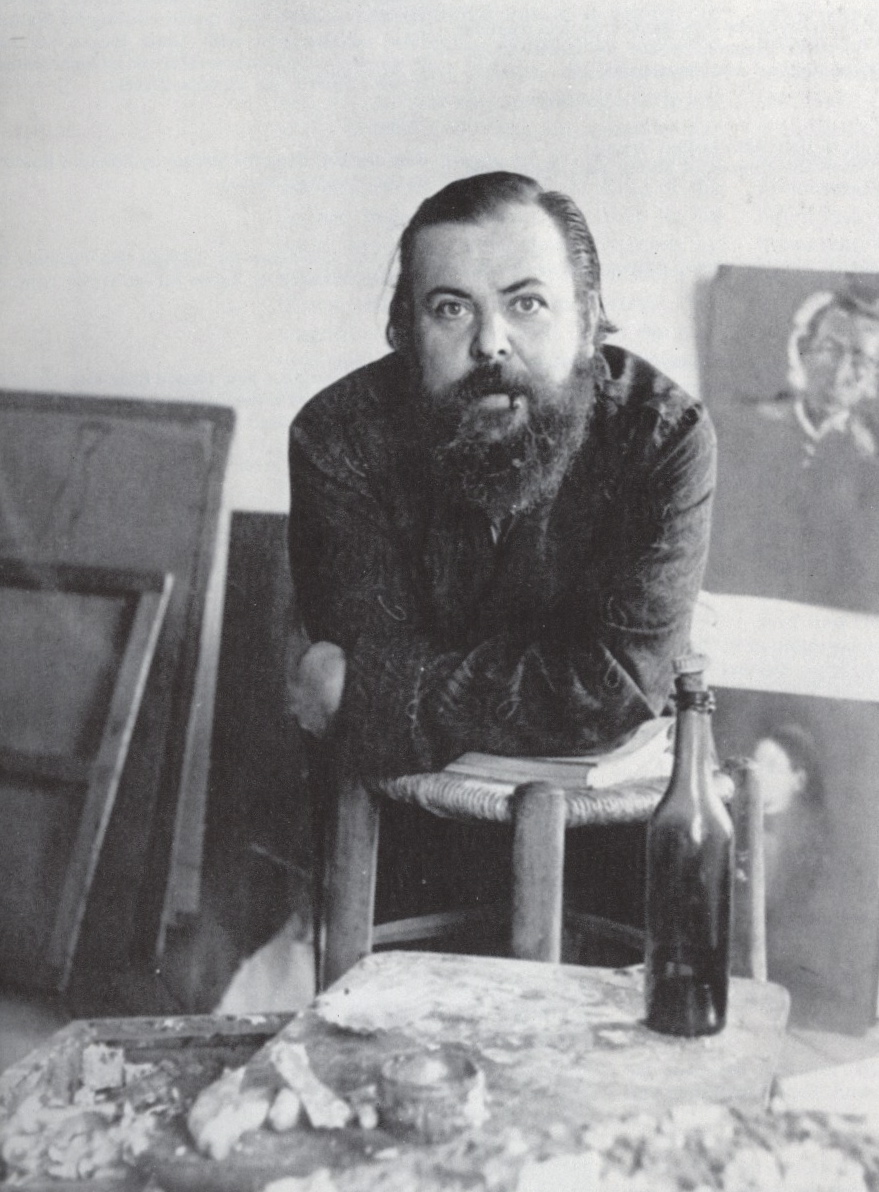

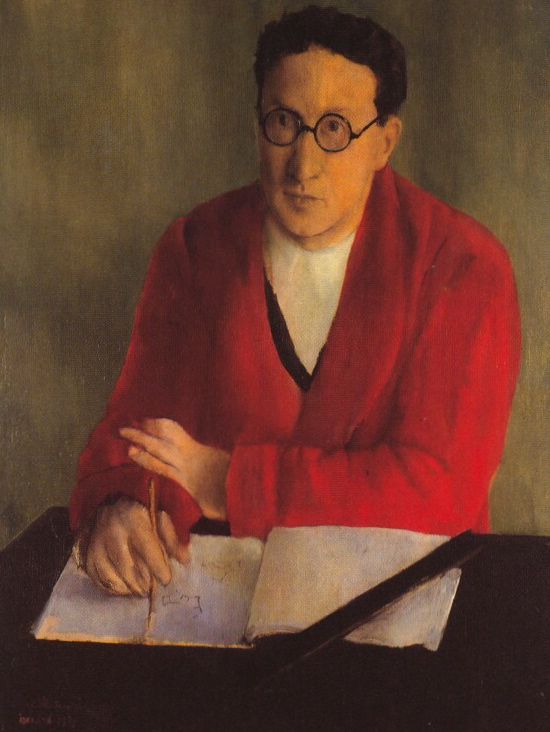

Christian Bérard, Self-portrait, 1948

Christian Bérard, Self-portrait, 1948

Oil on canvas, 18″ x 24″

Private collection, Paris

Christian Bérard (1902-1949) was a prodigiously-talented artist, whose tremendous facility across different fields, and his status as the darling of fashionable society in the Paris of the 1920s and 1930s, undermined his reputation as a serious painter. Bérard’s work confounded the critics because his work was unclassifiable—it existed outside the current theories of art, and he interchanged techniques and disciplines. Bérard’s ground-breaking set and costume designs, fashion and book illustrations, murals, decorative screens and interior designs all demonstrated a sensitive, fluid, graceful, elegant line.

Christian Bérard, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1932

Christian Bérard, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1932

Mural for Jean Cocteau’s flat, Paris

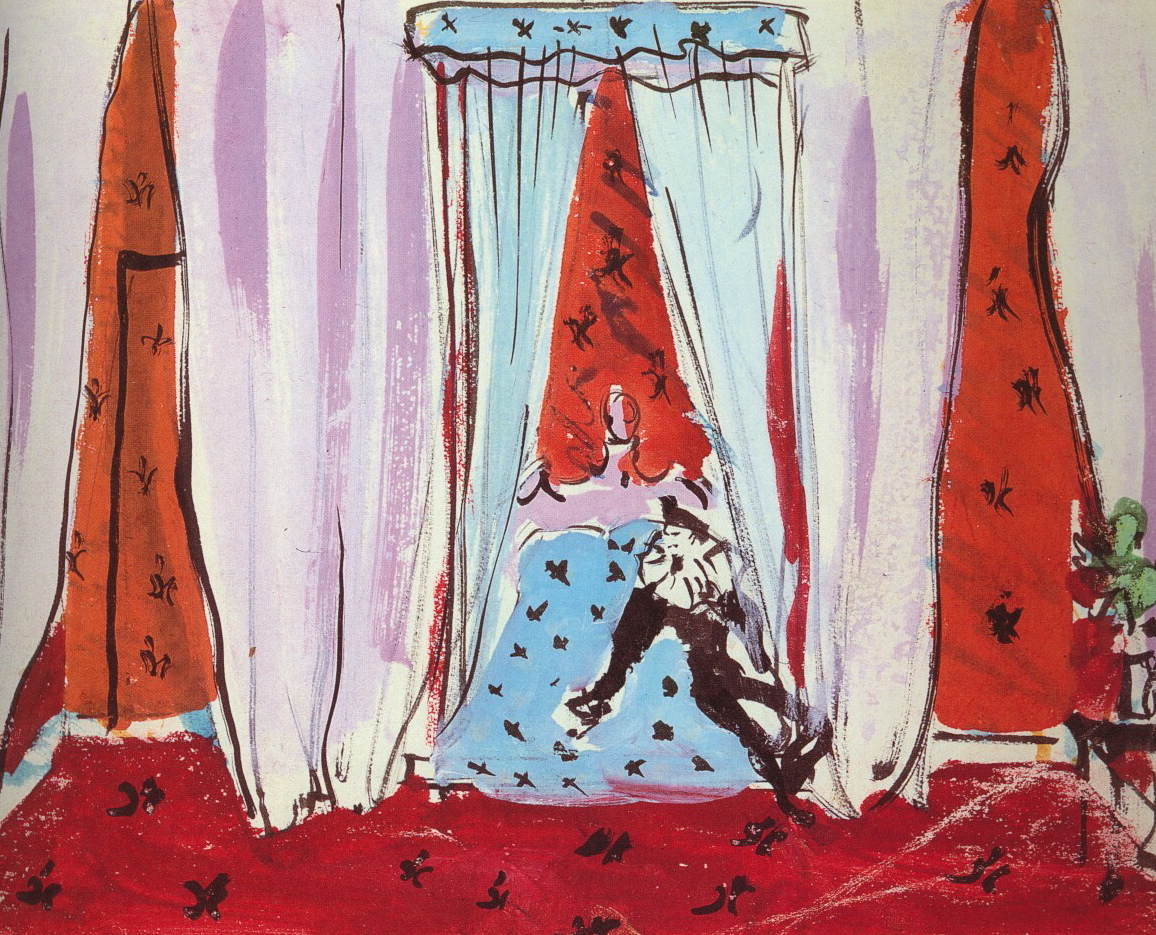

Christian Bérard, set for Margot, 1935

Christian Bérard, set for Margot, 1935

Margot’s Room at the Louvre, Act II, Scene 1

Gouache on paper

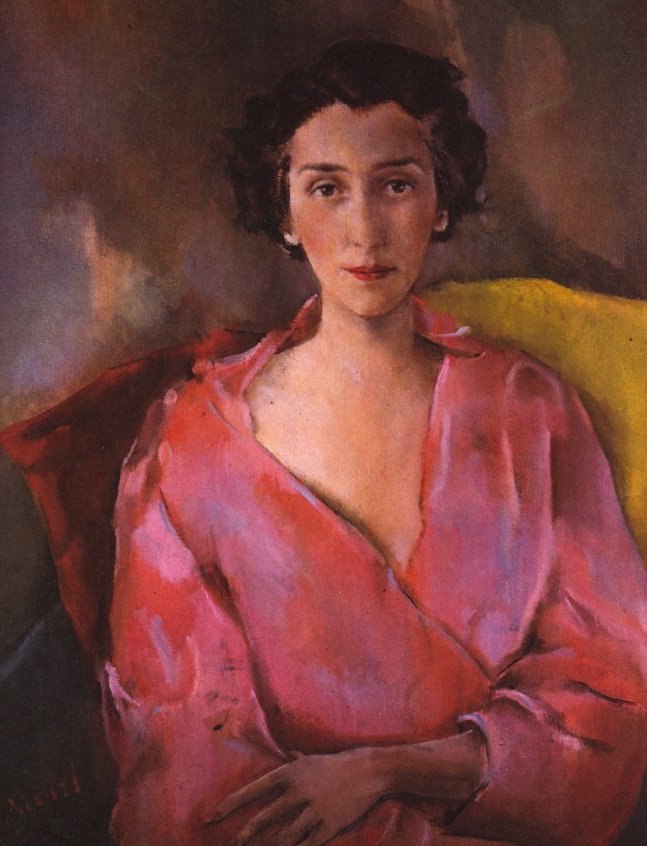

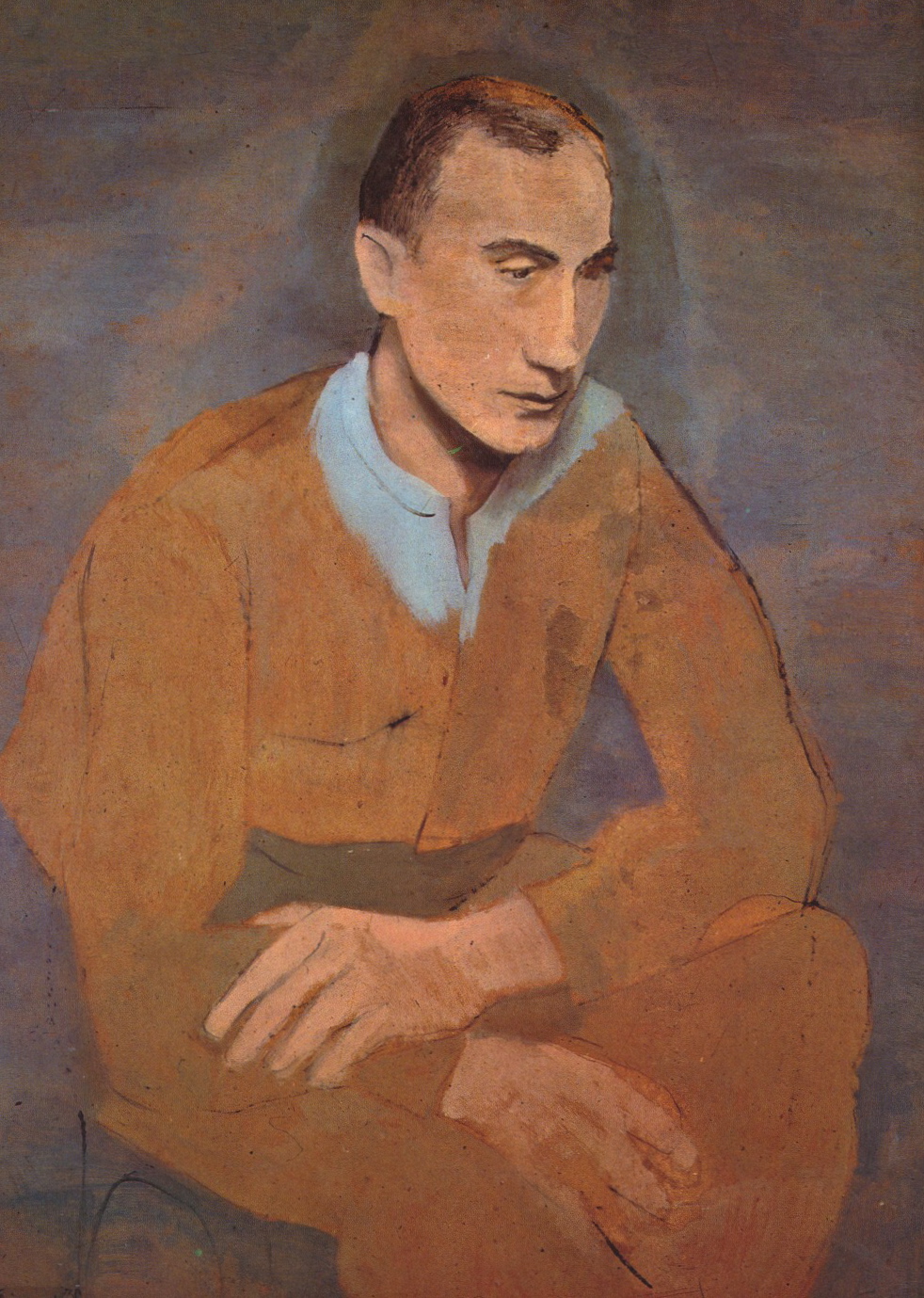

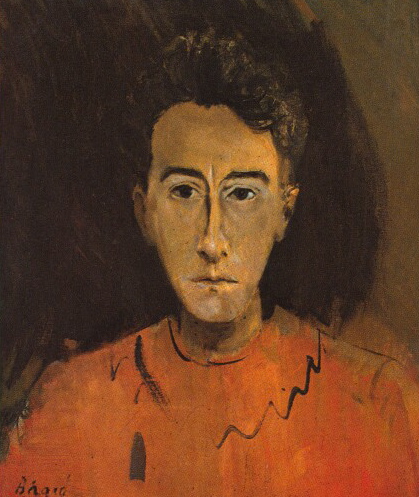

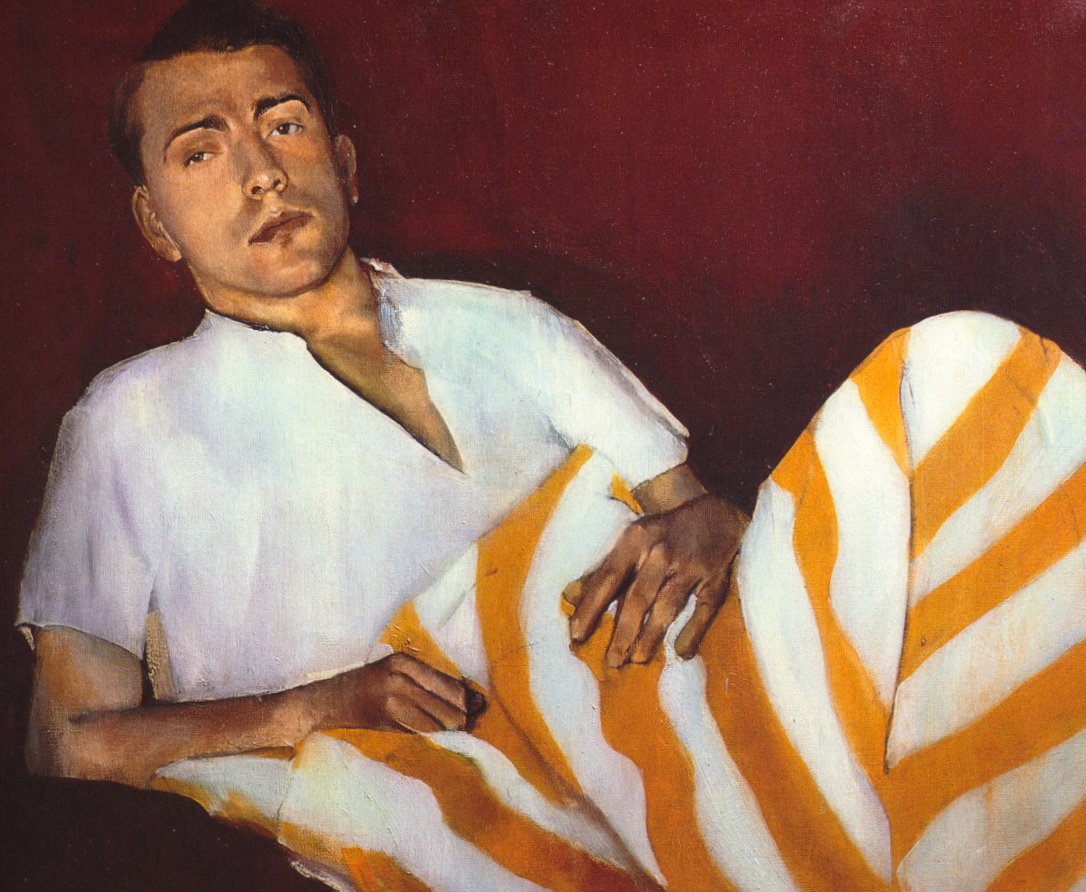

Bérard’s paintings, mostly portraits and self-portraits, added another dimension to his talent as a draughtsman. Painted with insight and great skill, in a neo-romantic, poetic style, they exhibit a deeply-felt humanism. His friend and partner of 20 years, Boris Kochno, remarked that when he was painting, Bérard’s usual childlike exuberance would vanish, and he would work with great concentration and intensity, seeming to take instruction from an unseen third party. Bérard often reused canvases, painting over work he was dissatisfied with—so one can occasionally glimpse ghost-like images, faint faces, emerging from some of his paintings.

Christian Bérard, Madame L., 1947

Christian Bérard, Madame L., 1947

Oil on canvas, 32″ x 26″

Private Collection

Christian Bérard, Boris Kochno, 1930

Christian Bérard, Boris Kochno, 1930

Oil on cardboard, 43″ x 31″

Collection Boris Kochno

Christian Bérard, Emilio Terry, 1931

Christian Bérard, Emilio Terry, 1931

Oil on canvas, 36″ x 28″

Private collection, Paris

Born in Paris in 1902, Bérard was the son of the official architect of the city of Paris, André Bérard. His mother’s early death from tuberculosis was traumatic for the young Bérard. After his wife’s death, the elder Bérard married his secretary, who joined him in the constant disparaging and belittling of his son’s talents, friendships and spending habits. Perhaps Bérard’s life-long desire to please and give pleasure, and his susceptibility to flattery, was a reaction to this early and intense hostility from his family.

Christian Bérard, 1932

Christian Bérard, 1932

Photograph, Hoyningen-Huene

Bérard showed artistic talent at a young age. As a child he filled sketchbooks with drawings of ballets and circus performances that he attended with his parents. He also copied the couture gowns from his mother’s fashion magazines, which at that time were heavily influenced by the Orientalism of Léon Bakst’s sets for Diaghilev’s ballets. As a young man, he studied at the Académie Ranson with Edouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis and had his first gallery show in 1925. His early work was collected by Gertrude Stein, and he did portraits of his friends Coco Chanel, Jean Cocteau, Cecil Beaton and Horst P. Horst.

Christian Bérard, Jean Cocteau, 1928

Christian Bérard, Jean Cocteau, 1928

Oil on canvas, 26″ x 21″

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Christian Bérard, Horst P. Horst, 1933/34

Christian Bérard, Horst P. Horst, 1933/34

Oil on canvas, 31″ x 41″

Private collection, New York

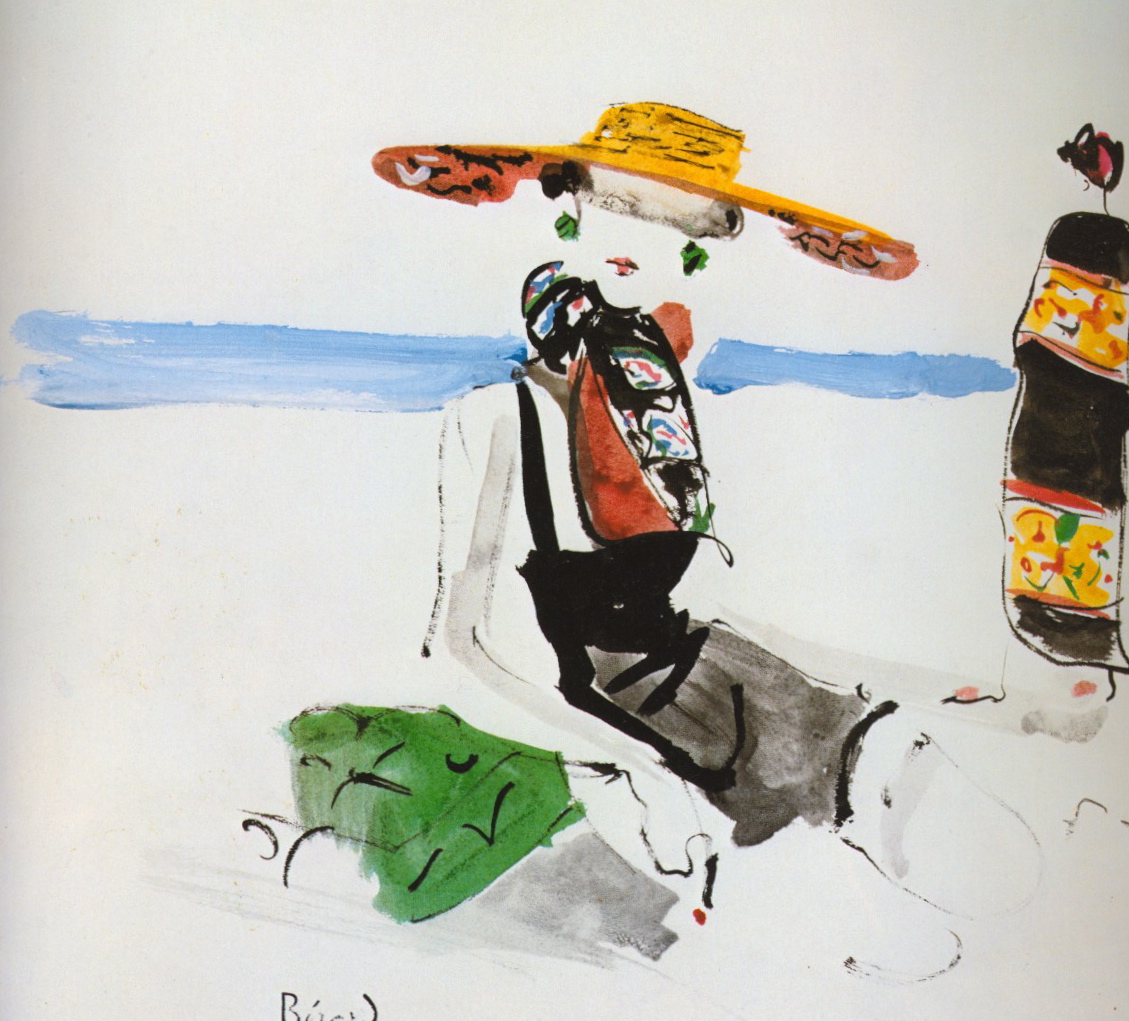

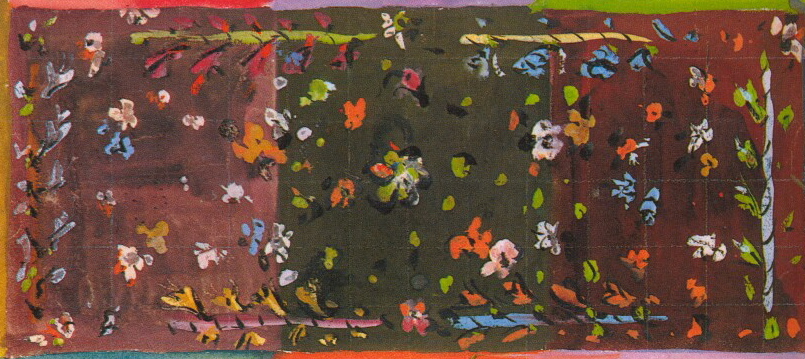

Throughout his career, when he needed the income, Bérard continued to do illustrations for fashion and interior design magazines such as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Art et Style, Formes et Coleurs and Style en France. He had a great eye for fashion and style, and his work elevated the art of fashion illustration, updating a Watteau or Fragonard sensibility for women’s fashion to the styles of the 1930s and 40s. His work often inspired the couture collections of designers like Christian Dior, Elsa Schiaparelli and Nina Ricci. Bérard also did some interior decoration and textile design—painting murals and decorative screens, designing rugs—as well as a line of scarves for Ascher Silks, London.

Christian Bérard, illustration, beachwear for Schiaparelli, n.d.

Christian Bérard, illustration, beachwear for Schiaparelli, n.d.

Christian Bérard, Scarf designed for Ascher Silks, London

Christian Bérard, Scarf designed for Ascher Silks, London

Christian Bérard, carpet design, c. 1940

Christian Bérard, carpet design, c. 1940

Made by Maurice Lauer/Aubusson and Cogolin, reissued 1951

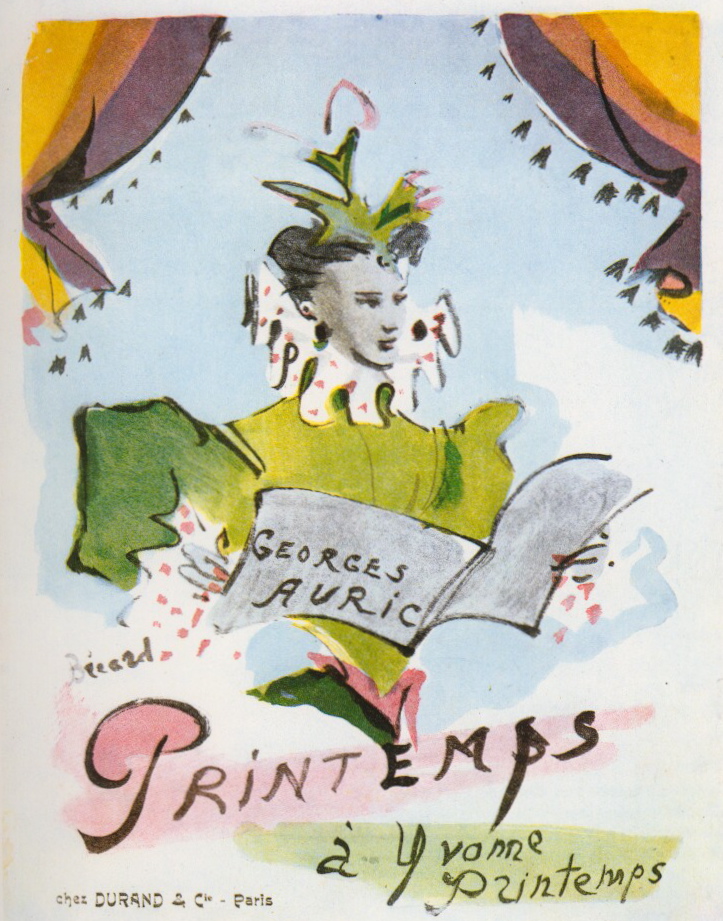

Bérard also continued to do illustrations for theater and ballet posters, music scores, and advertising throughout his life.

Christian Bérard, Sketch for an illustration of Gigi by Colette, n.d.

Christian Bérard, Sketch for an illustration of Gigi by Colette, n.d.

Pastel and gouache, 13″ x 8″

Christian Bérard, Poster for the Ballets des Champs-Elysées

Christian Bérard, Poster for the Ballets des Champs-Elysées

Christian Bérard, Empress Josephine

Christian Bérard, Empress Josephine

Illustration for Queens of France by Jean Cocteau and Guillaume, 1949

Drypoint

Christian Berard, Illustration for score by Georges Auric, 1935

Christian Berard, Illustration for score by Georges Auric, 1935

Gouache on paper

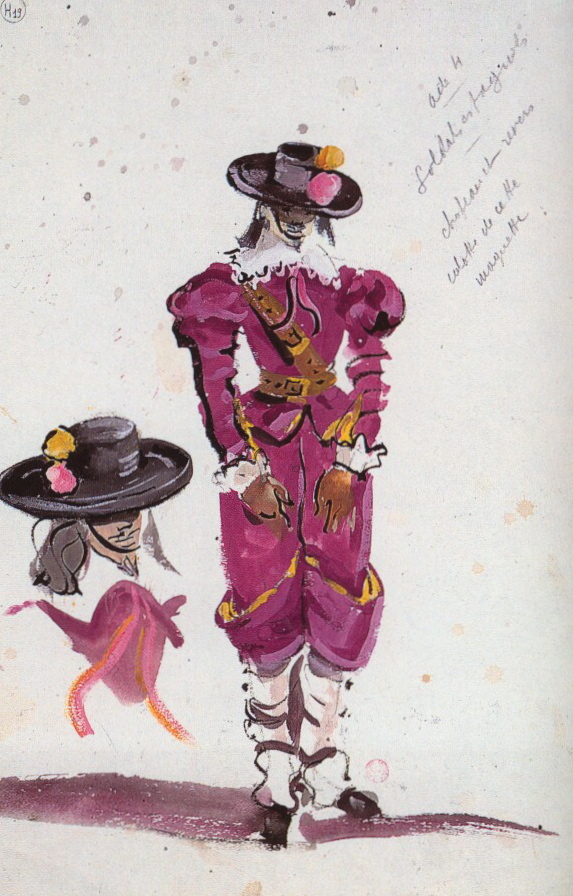

Christian Bérard was a large man, with fair hair, luminous blue eyes, and a rosy plump face that earned him the nickname Bébé, given to him by his friends because he resembled the baby in an advertisement for soap that was currently up all over Paris. Bérard’s appearance was often disheveled, he would stride into Maxim’s or other society nightspots in tattered paint-spattered smock and torn coveralls, with a large patterned scarf flung dramatically over his baggy workman’s jacket. Boris Kochno also recounts long walks through Paris at night—Bérard constantly noticing and pointing out glimpses of magical scenes, almost like a conjurer. Bérard never lost his childhood enjoyment of carnivals and street fairs and threw himself with great enthusiasm into the constant round of costume parties given by his friends. He excelled at spontaneously creating costumes from fabrics and items at hand.

Christian Bérard, sketch for Cyrano de Bergerac, 1938

Christian Bérard, sketch for Cyrano de Bergerac, 1938

Indian ink and gouache

Private collection

When agitated or absorbed in his work, Bérard could be very clumsy, and he could turn a well-ordered room into chaos in short order—leaving a wake of crumbled papers, overflowing ash trays, and stepped-on tubes of paint. He was also extremely witty and charming—his spontaneity, kindness and charisma made him very popular in fashionable circles. He was always creating—while dining with friends, like New York society hostess Elsa Maxwell, Bérard would constantly be drawing on table cloths, napkins, menus—caricatures, stage sets, costumes. The waiters would hover and often quickly whisk them away, usually to sell to collectors.

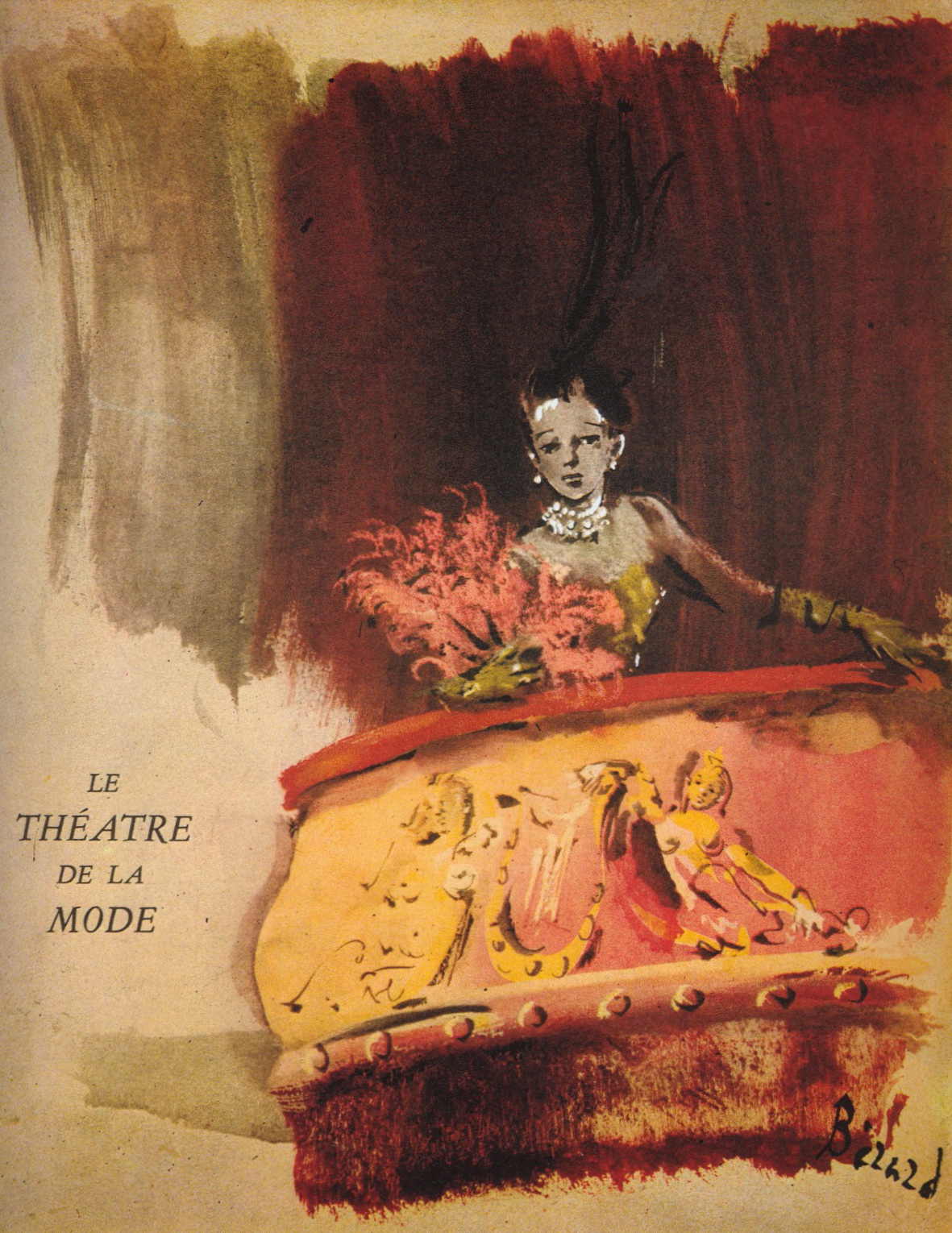

Christian Bèrard, Program for Le Théàtre de la Mode, 1945

Christian Bèrard, Program for Le Théàtre de la Mode, 1945

In 1930, Bérard designed his first theater set, for Jean Cocteau’s La Voix Humaine at the Comédie-Française. Cocteau was a life-long friend, and the work that Bérard is perhaps most famous for, is his set and costume design for Cocteau’s film masterpiece, La Belle et la Bête. Unfortunately, Bérard also shared Cocteau’s vice, the smoking of opium, which lead to a life of drug addiction, repeated sanatorium cures, and contributed to his early death.

Christian Bérard, sketchess for sets for Cocteau’s La Belle et La Bête, 1946

Christian Bérard, sketchess for sets for Cocteau’s La Belle et La Bête, 1946

Chalk and gouache on black paper

Private Collection

In 1931, Bérard joined the company of the Ballet Russes in Monte Carlo, working with choreographer George Balanchine on the ballet Cotillon. Balanchine had taken over for ballet impresario and founder of the Ballet Russes, Sergei Diaghilev. Balanchine continued in Diaghilev’s tradition of scouring the garrets of Montparnasse and Montmartre to find unknown choreographers, set designers or musicians to collaborate with. At first Balanchine declined to work with Bérard because he thought his work was already too well-known as an artist and illustrator, but the quality of Bérard’s work caused him to change his mind.

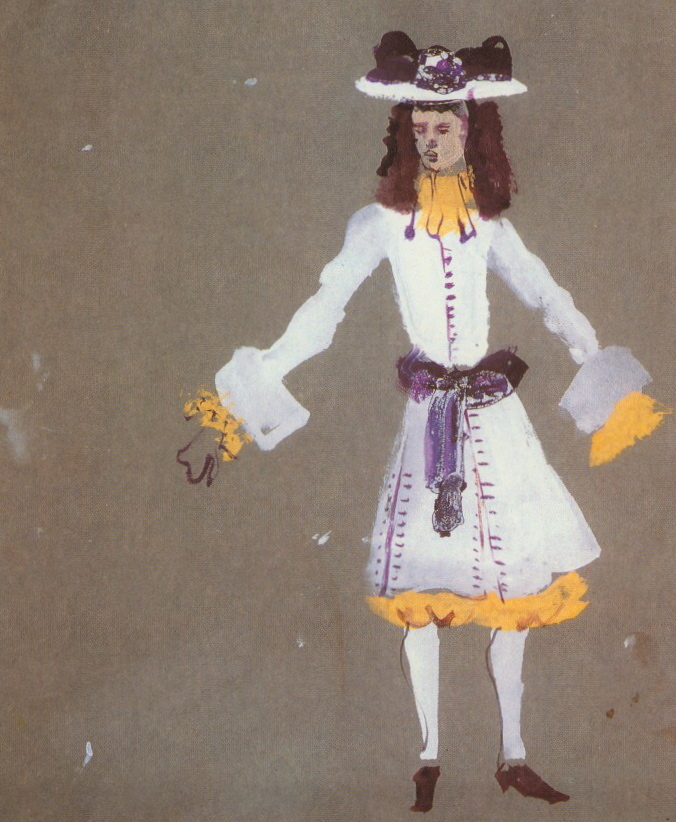

Christian Bérard, sketch for L’Ecole des Femmes, 1936

Christian Bérard, sketch for L’Ecole des Femmes, 1936

Horace’s Costume, Gouache

In the 1930s, Bérard did the sets and costumes for four ballets as well as many plays, such as Moliere’s L’Ecole des Femmes at the Théàtre de l’Athenée in 1936. He also worked with Jean Genet and Jean Giraudoux, among others. Bérard’s work was revolutionary and changed theater design forever—his set for L’Ecole consisted of a small garden, two flowerbeds and 5 chandeliers. He believed that sets should serve and enhance the work, he was always subtracting elements, leaving just the essentials. His set for Léonid Massine’s ballet set to the music of Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique, was a masterpiece of delicate, weightless friezes. Except for the judicious use of deep red, Bérard eschewed bright colors, believing that pale, soft color better served the performances. To see Bérard working on a set was to see an outpouring of inventiveness. After Bérard’s death, Jean Cocteau said of working with his friend:

Christian Bérard was my right hand. Since he was left-handed, I had a special, clever, gracious, light right hand: a magical hand.

You may imagine the emptiness left by an artist who guessed all, and with the dilligence of an archeologist, conjured up naked beauty from the thin air where she resides. Bérard is dead, but that is no reason to stop following his instructions. I know what he would say about anything, in any circumstances. I listen to him and carry out his orders.

Christian Berard died in 1949, while at work on the costumes and sets for Les Fourberies de Scapin at the Théàtre Marigny, working with friends director Louis Jouvet and actors Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud. After giving some final instructions, Bérard stood up and said: “Well, that’s that,” and collapsed from a cerebral embolism. Jean-Louis Barrault wrote:

If I had to chose only one among the many impressions of Christian Bérard that spring to mind, it would be one that soon became for him a profession of faith: the joy of living, to the extent of perishing from that joy…It is as if, while I think intensely of him, all of the Bérards leaping about me reply:

‘Love of life is based on suffering, anguish, nostalgia, sorrow and sadness…that’s true, but all that is the source of joy.’

Wider Connections

Christian Bérard’s work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Menil Collection, Houston and the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas.

Christian Bérard, by Boris Kochno, with an introduction by John Russell. Thames and Hudson, 1988.