The very idea of a bird is a symbol and a suggestion to the poet. A bird seems to be at the top of the scale, so vehement and intense his life. . . . The beautiful vagabonds, endowed with every grace, masters of all climes, and knowing no bounds — how many human aspirations are realised in their free, holiday-lives — and how many suggestions to the poet in their flight and song! — John Burroughs (1837-1921)

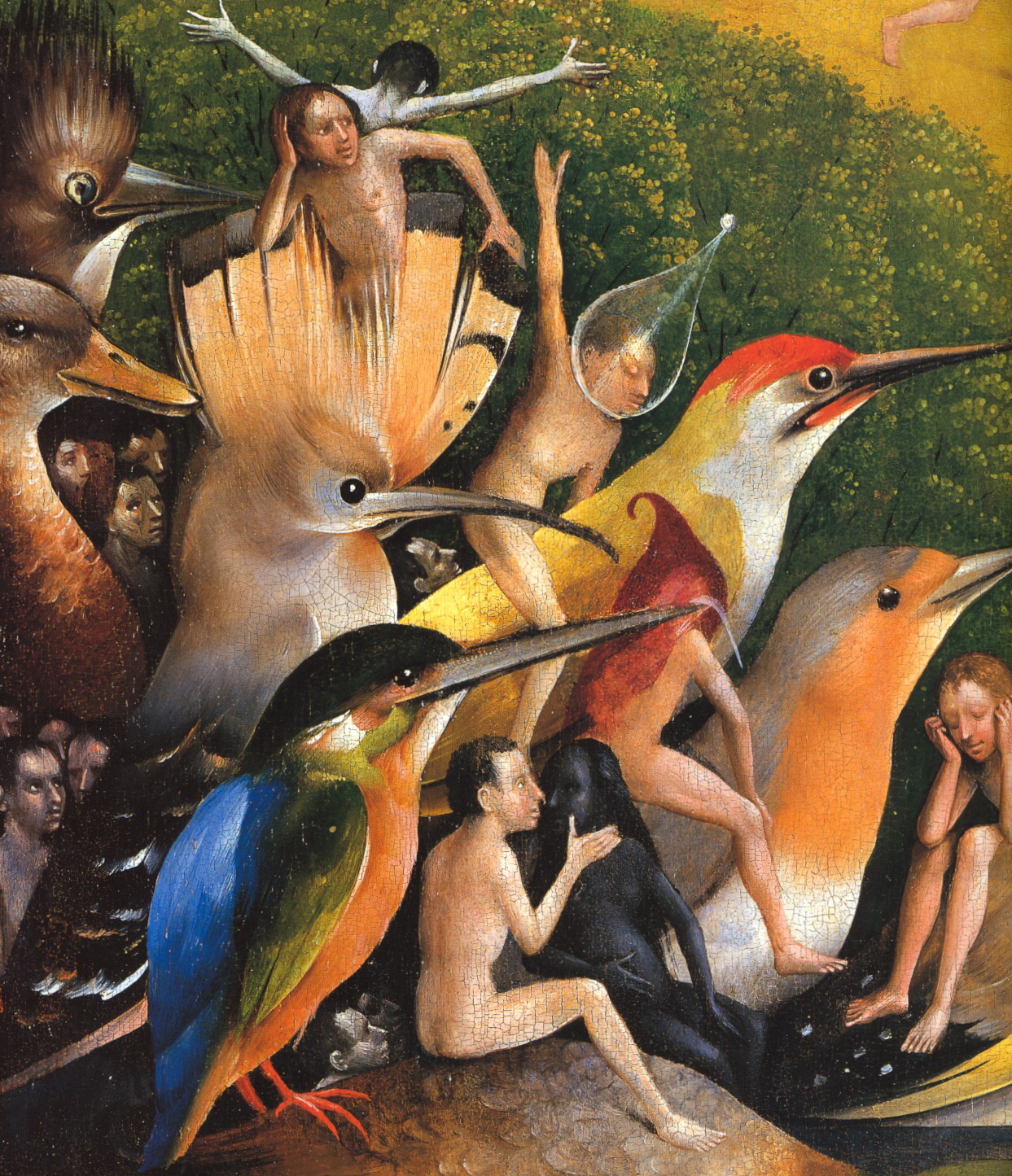

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, center panel, detail,

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, center panel, detail,

c. 1503-04

Oil on wood

The Prado, Madrid

In his mysterious and enigmatic allegorical triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516) painted enormous fruits and giant birds cavorting with tiny people of all races in a sumptuous garden. This painting presents a complex labyrinth of seemingly contradictory ideas and motifs. The triptych has been interpreted as a critique of the Catholic Church, a panorama of the Creation or a reflection on the humanist writings of Thomas More. Whatever his intent, Bosch’s giant birds are wonderful examples of the way that painters throughout history have used birds—as symbols of nature and the soul, as go-betweens, harbingers and messengers—and as intriguing examples of the wonders of nature.

Here are some of my favorites.

Roman garden painting, detail, first century A.D.

Roman garden painting, detail, first century A.D.

Casa del Bracciale d’Oro, Pompeii

Roman garden painting, detail, first century A.D.

Roman garden painting, detail, first century A.D.

Casa del Bracciale d’Oro, Pompeii

Gardens were often depicted in tomb and wall paintings in the ancient world. There is evidence that many types of gardens flourished—domestic gardens for both relaxation and as sources of food, gardens with sacred and religious meaning, cemetery gardens, opulent orchards and parks. Where there are gardens, there are birds.

Hans Holbein, A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, c. 1526-1528

Hans Holbein, A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, c. 1526-1528

Oil on oak

National Gallery of Art, London

German painter Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543) was a very versatile artist who did portraits, religious paintings, frescoes and woodcuts, as well as designing jewelry and metalwork. Holbein first traveled to England in 1528 with an introduction to Thomas More from the Renaissance Humanist scholar Erasmus, whose portrait Holbein had painted in 1523. Holbein moved to England permanently in 1532, as court painter to Henry VIII, and there he perfected his art as a portraitist. This wonderfully detailed painting is a study in contrasts, the serious pose of the sitter playing against the lively squirrel and starling (which may have represented the lady’s family coat of arms.) A luminous and rich blue background sets this enigmatic and fascinating portrait off like a jewel.

Georg Flegel, Fruit and Dead Birds, n.d.

Georg Flegel, Fruit and Dead Birds, n.d.

Oil on canvas

Private collection, Germany

German still-life painter George Flegel (1566-1638) specialized in paintings of tables set for meals with food, wine and flowers. I find this particular painting of Flegel’s very unusual and idiosyncratic. The elements of the composition are very deliberately laid out on the table and amidst the dead birds, feathers and fruits—all rather scientifically painted in a presentational manner—is perched a little goldfinch, very much alive.

Melchior d’Hondecoeter, The Floating Feather, c. 1680

Melchior d’Hondecoeter, The Floating Feather, c. 1680

Oil on canvas

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Melchior d’Hondecoeter (1636-1695) was a Dutch Baroque painter who specialized in painting animals, particularly birds. What is interesting to me about d’Hondecoeter is that he didn’t paint birds merely as trophies of the hunt or table, but as creatures with moods as well as relationships, feelings and inner lives.

Jan van Kessel, Concert of Birds, c. 1660-1670

Jan van Kessel, Concert of Birds, c. 1660-1670

Oil on copper

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Flemish painter Jan Van Kessel (1626-1679), the grandson of the great floral painter Jan Breughel the Elder, did beautifully detailed intimate paintings on copper. He was an avid student of the scientific naturalism of his day and excelled at painting insects. I am particularly interested in his panoramic scenes of birds—with their attention to detail and rich coloration, they have a cabinet of curiosities ambiance. Van Kessel also did some very beautiful still lifes, like this one, which includes a lively little bird that is depicted with wonderful movement and energy.

Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654

Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654

Oil on panel

Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis, The Hague

This delightful painting by Dutch painter Carel Fabritius (1622-1654) is very much a portrait—you feel he has captured the essence of a particular bird. Fabritius, a student of Rembrandt, was very interested in exploring spatial effects and trompe l’oeil. This little goldfinch looks like he could fly off his perch at any moment—if he was not held captive by the little chain attached to his leg. Fabritius very much created his own style. Eschewing the dark backgrounds and dramatically lit subjects popular at the time, he applied paint thickly, using a light-colored textured background and subtle lighting on his subjects.

Indian miniature, Akbar period, 1600-1605

Indian miniature, Akbar period, 1600-1605

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Royal figures with their falcons are a fairly common theme in Indian miniatures. In this beautifully naturalistic portrait, the bird is imbued with a definite personality and temperament. Only a member of a royal family would have worn such a magnificent robe. The silk brocade, which depicts animals, birds and plants in a lush landscape, was probably woven in Iran.

Mark Catesby, The White Crown Pigeon, The Coco Plum

Mark Catesby, The White Crown Pigeon, The Coco Plum

Natural History, Volume 1, Plate 25

Hand-colored Etching, London, 1727-1731

Mark Catesby (1682-1749) was an English naturalist who spent 10 years in the American colonies observing the natural history of the New World and collecting specimens. The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, which he wrote and illustrated, is a magnificent achievement. Catesby’s etchings were innovative—whenever possible, he drew from life, and he often portrays his subjects in flight or in motion, with bits of plants and landscape that suggest their native habitat. His fascination and love of the natural world is evident in each illustration, especially the ones from the original edition, which he personally hand-colored.

John Anster Fitzgerald, The Captive Robin, c. 1864

John Anster Fitzgerald, The Captive Robin, c. 1864

Oil on canvas

Private collection

At first glance, the work of Victorian fairy painter John Anster Fitzgerald (1819-1906) is very deceptive—the intense, saturated colors and the beauty of the images initially distract from the often macabre, nightmarish or sadistic subtexts. There’s plenty of evidence that Fitzgerald’s imagery owed more than a little to opium and laudanum use, not an uncommon vice in Victorian England. Robins have a complicated role in fairy-lore which is often ambiguous—they are variously allies and enemies. Fitzgerald painted a number of paintings about robins. As was often the case with fairy paintings, The Captive Robin is mounted in a large hand-made gilded twig frame that is quite extraordinary.

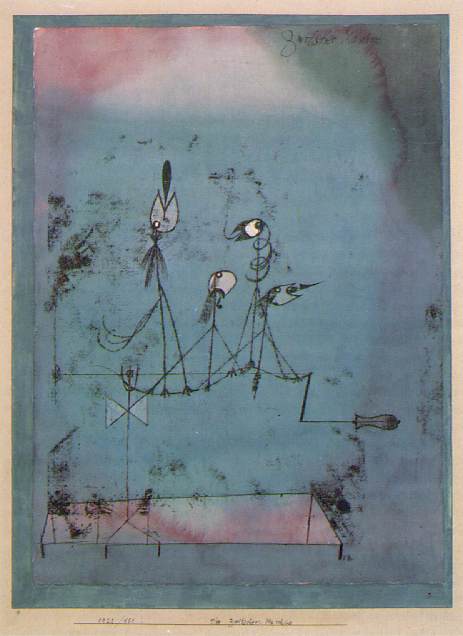

Paul Klee, Twittering Machine, 1922

Paul Klee, Twittering Machine, 1922

Oil transfer drawing on paper with watercolor and ink on board with gouache and ink borders

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Swiss artist Paul Klee (1879-1940) brings us into the modern era, which reveals a new kind of menace. His Twittering Machine seems to be about the uneasy alliance between nature and the mechanical, with the distinct possibility that mayhem will ensue. Klee’s nervous, edgy line, contrasted with the soothing blue and violet background, adds another layer of meaning to this unsettling fusion of bird and machine.

René Magritte, The Natural Graces, c. 1961

René Magritte, The Natural Graces, c. 1961

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Belgian Surrealist painter René Magritte (1898-1967) transformed and juxtaposed every day things—the changed context jolts us into seeing things we thought were familiar in a new light. Magritte described painting as:

…the art of putting colors side by side in such a way that their real aspect is effaced, so that familiar objects—the sky, people, trees, mountains, furniture, the stars, solid structures, graffiti—become united in a single poetically disciplined image. The poetry of this image dispenses with any symbolic significance, old or new.

Remedios Varo, Troubadour, 1959

Remedios Varo, Troubadour, 1959

Oil on masonite

Private collection

Remedios Varo (1908-1963) was a Spanish-born Surrealist painter who adopted Mexico as her home. Varo’s imagery was drawn from nature, and she had an intense and abiding interest in science. As a child she often visited the Prado with her father, and it there that she discovered Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, whose mixture of wit and menace she found inspiring. Birds play a large role in Varo’s personal iconography and appear often in various stages of transformation in her work.

Walton Ford, Eothen, 2001

Walton Ford, Eothen, 2001

Watercolor, gouache, pencil and ink on paper

Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York

American watercolorist and printmaker Walton Ford (1960-) creates beautifully rendered large-scale images of nature gone amok. At first we are seduced by the beauty of the image, then we realize that the work is haunted by a sense of impending doom—something sinister and violent is taking place. Ford’s work operates on several levels at once, seeming to celebrate the romantic beauty of the work of naturalist John James Audubon while it satirizes colonialism and consumerism, mourns the extinction of species and dispassionately chronicles the destructive forces inherent in nature.

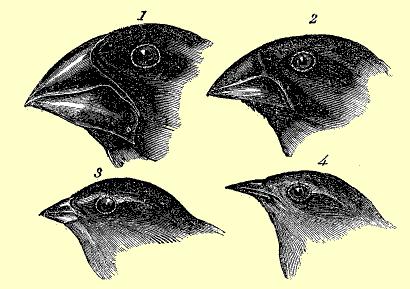

Darwin’s finches from the Galapagos Islands

Darwin’s finches from the Galapagos Islands

No other creatures in nature represent as complex and intriguing a variety of qualities as birds. Artists have pictured them in many guises—as harbingers of doom, symbols of resurrection and as intermediaries between man and the Divine. They represent dreams, magical powers, clairvoyance and the mysteries of the unconscious. With their enormous variety and often spectacular beauty they embody the infinite and fearful powers of nature. As Charles Darwin wrote:

We behold the face of nature bright with gladness. We do not see, or we forget, that the birds singing around us live on insects or seeds, constantly destroying life.