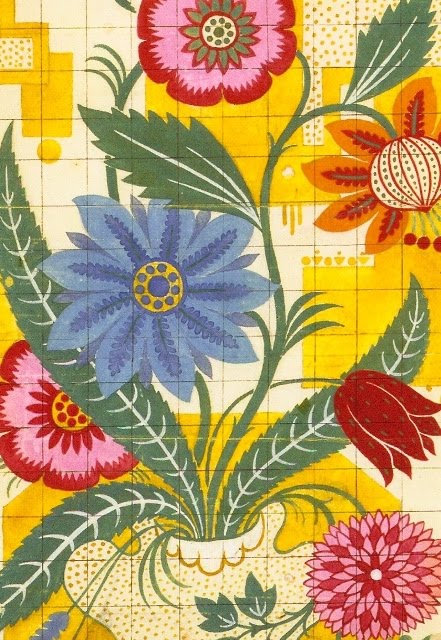

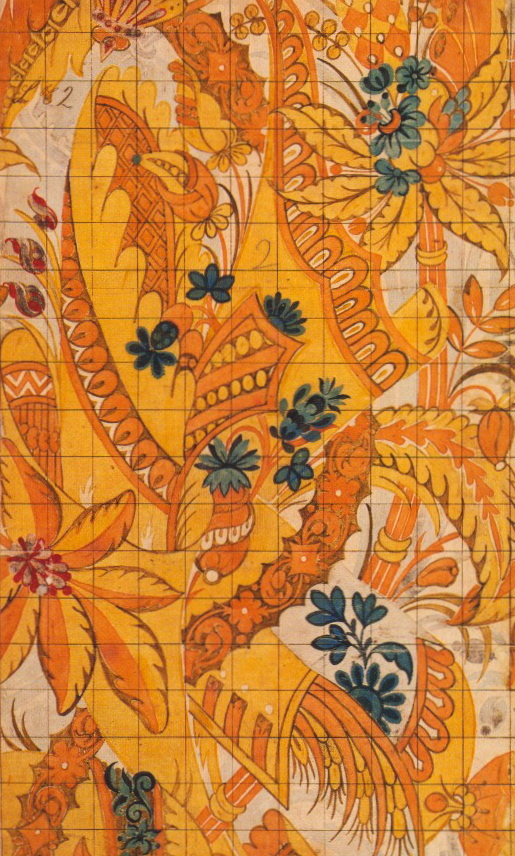

James Leman, silk design, 1717

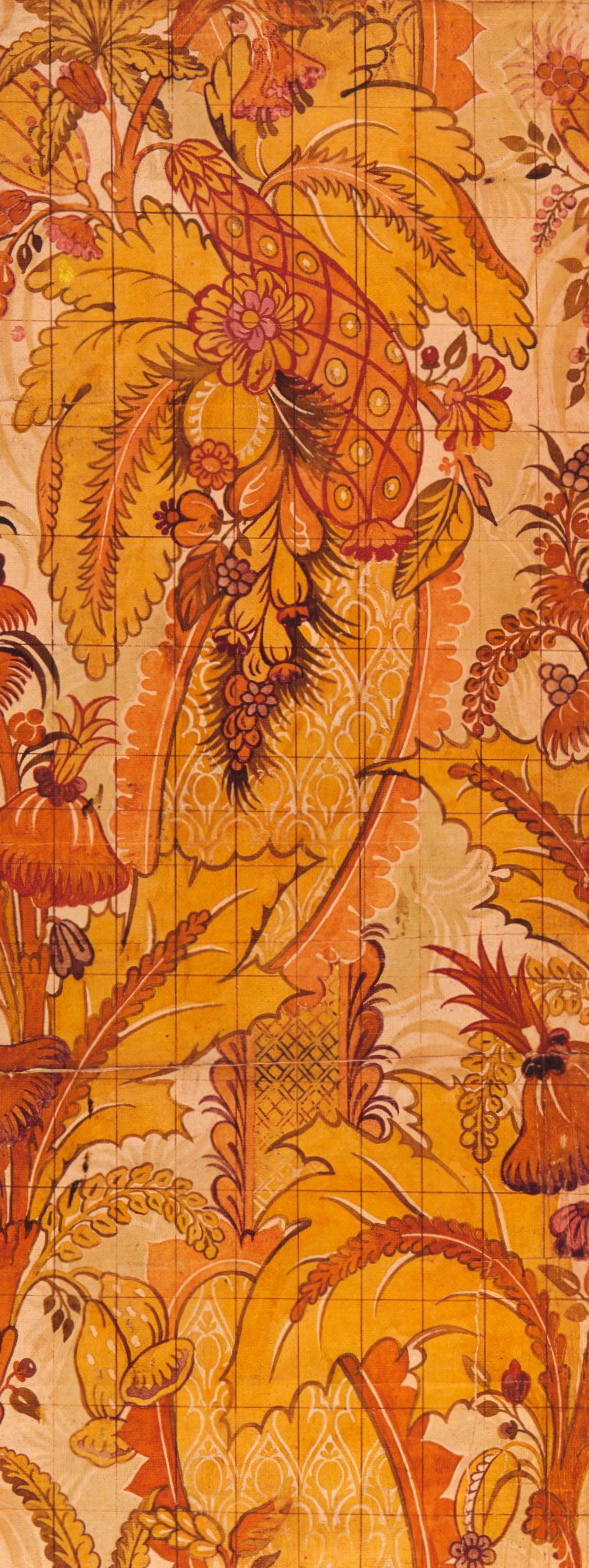

James Leman, silk design, 1717

Watercolor on paper

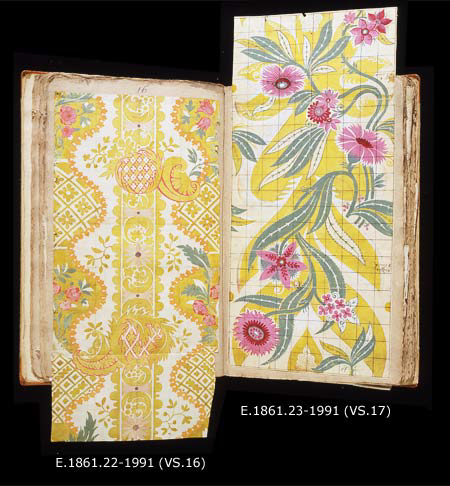

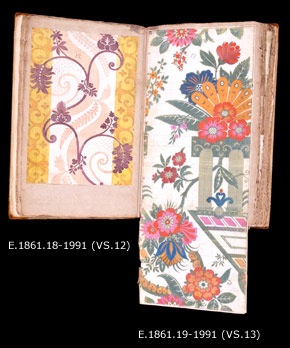

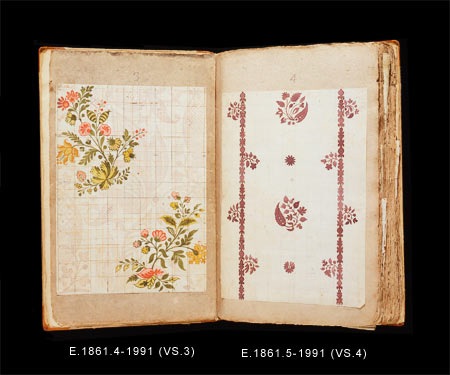

James Leman (c.1688-1745) was one of the pre-eminent designers of silk textiles in the first half of the 18th century in England. In addition to being a designer, Leman was also a silk manufacturer and likely a master weaver as well, a combination of talents that was common in the silk-weaving industry in Lyons but rare in England. James Leman, of Huguenot descent, was the son of Peter Leman, a master weaver. He apprenticed to his father in 1702 and took over the family business in 1706. Ninety-seven of Leman’s watercolor designs, bound in an original Spitalfields design book and dated 1706-1730, are in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. It’s hard to believe that these designs, the color so fresh and vibrant, and the patterns so modern, are 300 years old. Note that the yellows and oranges in the watercolors represent various colors of metallic threads.

Album of silk designs by James Leman in the Victoria & Albert Museum

Various dates, 1706-1730, watercolor on paper

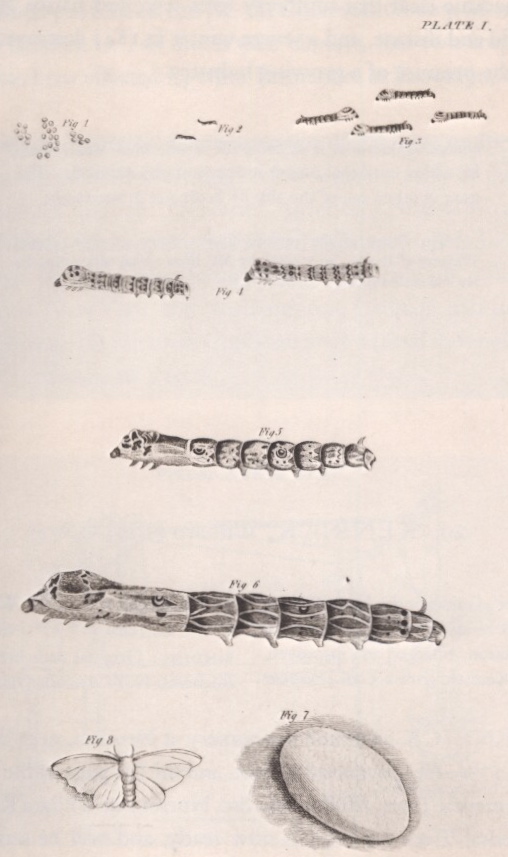

The influence of the Huguenot emigres on England’s textile industry was enormous, because they brought their weaving skills with them. Until that point the English silk-weaving industry had been quite small—with the expertise of the Huguenot weavers, it blossomed. The Huguenots, Protestants from France, were subject to several waves of persecution in the 16th and 17th centuries. They left France by the thousands and contributed greatly to the textile industries of Britain, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. In reaction to the arrival of an early wave of Huguenot emigres in search of employment, King James I, who ascended to the throne of England in 1603, and was an admirer of silk garments, attempted to introduce sericulture to England. James commissioned a book on the subject and provided the landed gentry with a supply of mulberry seeds and trees. The experiment was not a success, and weavers had to continue to rely on imported silk, which, as the demand grew, Britain obtained from China, Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

The life cycle of the silk worm, 1831

lithograph, signed W.S. & J.B. Pendelton of Boston

from Jonathan Cobb’s Manual containing information respecting the growth of the Mulberry Tree

An interesting aside to the Huguenot story is that one of the most prominent Huguenot families to settle in England was the Courtaulds, who fled from France in the 1680s and later became silk weavers. A descendant of this family, Samuel Courtauld, who took control of the company in 1908 (the firm invented rayon, a synthetic silk, in 1910), achieved great renown as an art collector. In 1932 he founded the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, to which he bequeathed his collection upon his death in 1947.

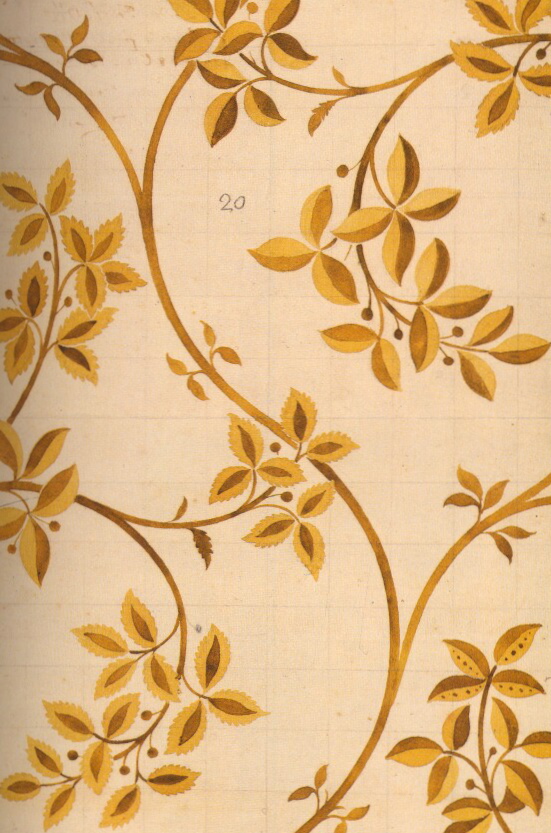

James Leman, silk design, 1706/7

James Leman, silk design, 1706/7

Watercolor on paper

James Leman, silk design, 1710

James Leman, silk design, 1710

Watercolor on paper

James Leman, silk design, 1711/12

James Leman, silk design, 1711/12

Watercolor on paper

By 1700 the center of silk manufacturing in England was in Spitalfields, now part of East London. Spitalfields has had an illustrious history. On the site of what was in Roman times a cemetery, England’s largest medieval hospital was constructed—The New Hospital of St Mary without Bishopgate—in 1197. The name Spitalfields is a contraction of “hospital fields.” The area went through many transformations, eventually becoming a textile center—first for laundresses, then for calico dyeing, then, in the 18th century, silk weaving. After the silk-weaving industry failed in the 1820s, the area declined and eventually became a center for furniture building, boot-making and later, tailoring. In Victorian times it became seedier still, and was famous for grisly murders by Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel Strangler. The area is largely gentrified now, and when the historic Spitalfields Market area underwent a major renovation in the 1990s, the Roman cemetery became an important archeological dig and yielded many stunning artifacts, including sarcophagi with human remains.

Court dress, British, c. 1750

Court dress, British, c. 1750

Silk, metallic thread

Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

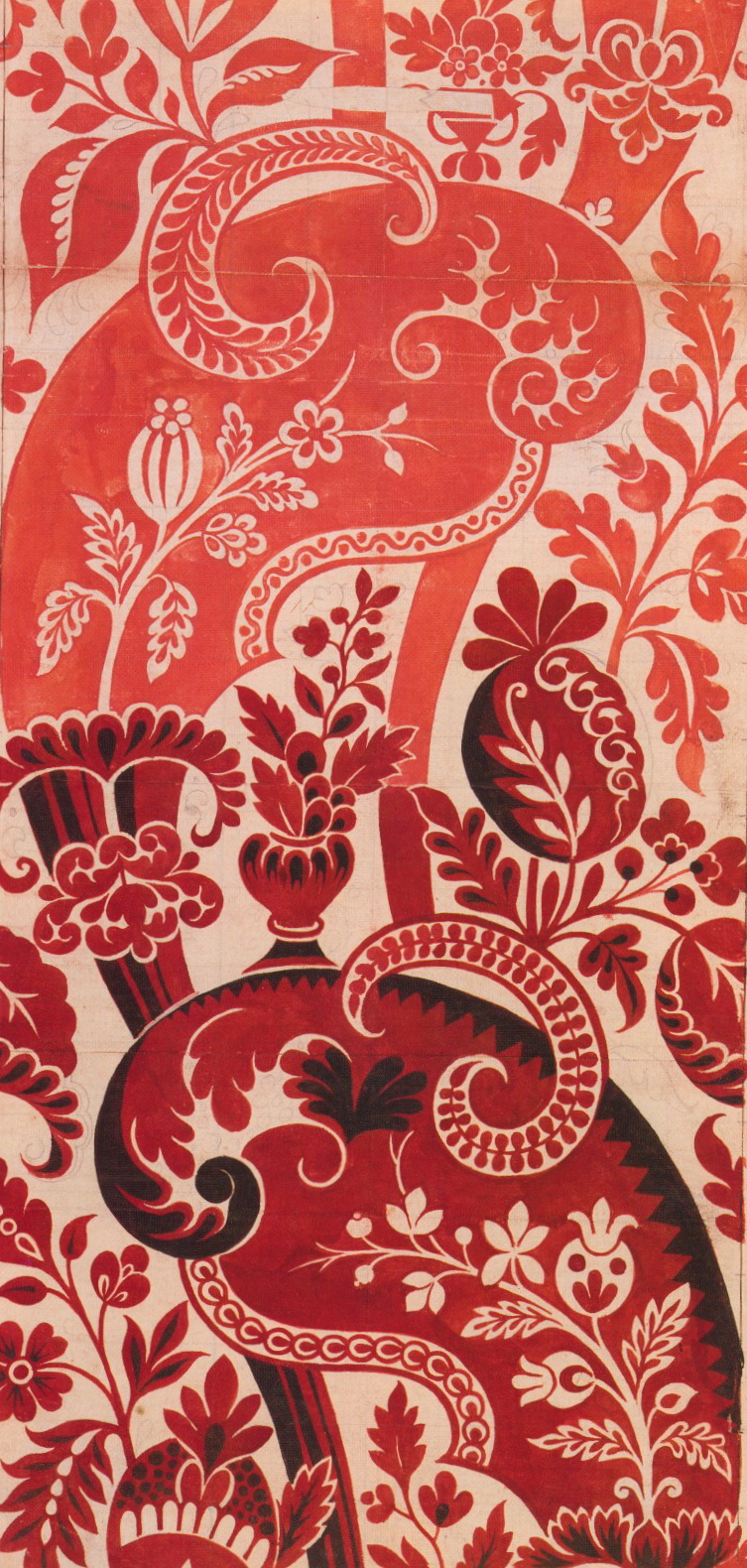

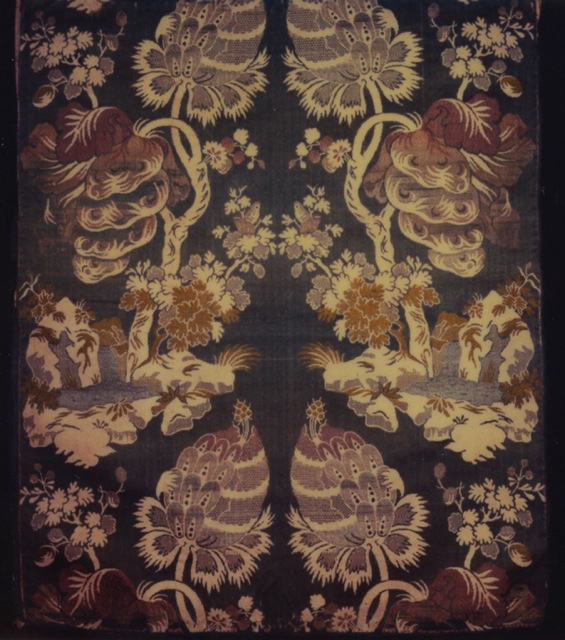

The development of the silk industry in 18th century England paralleled that of the rest of the decorative arts in England—following a trajectory from simplicity through the development of the elaborate English Rococo style, then back to Neoclassical. Over the course of the century, design influences went back and forth across the English Channel, each decade brought stylistic changes. At the beginning of the 18th century, designers began to leave behind the excesses of the later 17th century—patterns became less exotic and more naturalistic. In the 1730s french silk designer Jean Revel (1684-1751) invented a radical new technique, points rentrés, a method that enabled the weavers to create shading. These three-dimensional patterns were often woven on a plain silk background to better show off the larger, bolder, designs.

Fabric in the style of Jean Revel, c.1733-35

Fabric in the style of Jean Revel, c.1733-35

The Art Institute of Chicago

In the 1740s, the pendulum swung again, the English “flowered silks” style emerged with more naturalistic botanical detail, in clear, soft colors on plain backgrounds. By mid-century French influence returned and through the 1750s and 1760s more background pattern re-emerged, designs became more stylized, the fabrics became stiffer with more metallic threads. By the 1770s, as styles of dress become more informal, patterns became smaller and were often combined with stripes. By the end of the century, Neoclassic patterns dominated.

As a manufacturer, James Leman employed other silk designers: two of the best known are Christopher Baudouin and Joseph Dandridge.

Christopher Baudouin, silk design, 1718

Christopher Baudouin, silk design, 1718

Watercolor on paper

Joseph Dandridge, silk design, 1718

Joseph Dandridge, silk design, 1718

Watercolor on paper

Moving towards the mid-eighteenth century, another extremely important English designer began working in Spitalfields, Anna Maria Garthwaite (c.1688-1763). Garthwaite was born in Leicestershire and moved to London in 1730, where she worked freelance, producing many bold damask and floral brocade designs over the next three decades. She was interested in naturalistic floral patterns and adapted Revel’s points rentrés technique. Hundreds of her designs in watercolor have survived and are preserved in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Fortunately, several excellent examples of clothing made from her textile designs survive, and there is at least one contemporary portrait in which the sitter is wearing a dress made from a documented Garthwaite design.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, Waistcoat, 1747

Anna Maria Garthwaite, Waistcoat, 1747

Silk, wool, metallic thread

Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Robert Feke, Mrs. Charles Willing of Philadelphia, 1746

Robert Feke, Mrs. Charles Willing of Philadelphia, 1746

Oil on canvas

Fabric design, Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1743

Anna Maria Garthwaite,1742

Anna Maria Garthwaite,1742

Silk brocade

The Fashion Museum, Bath

Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1742

Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1742

Blue and silver brocaded silk

Below is a silk brocade dress, made of fabric from Garthwaite’s design, in the Museum at FIT, followed by a William Hogarth painting at The Frick Collection. I am making no claim that the sitter’s gown is a Garthwaite design, but I was struck by the similarity.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, n.d.

Anna Maria Garthwaite, n.d.

Silk damask gown

Museum at FIT, New York

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Miss Mary Edwards, 1742

William Hogarth (1697-1764) Miss Mary Edwards, 1742

Oil on canvas

The Frick Collection

All of these 18th-century brocade and damask fabrics were woven on a drawloom. These were hand looms with a system of cords that would lift certain warp threads so that when the weft thread was passed through, intricate repeat patterns could be produced. The cords were handled by a “drawboy” who sat on the top of the loom. This method was laborious, slow and took quite a bit of skill, and attempts were made improve the equipment and speed up the process. Philippe de Lasalle (1723-1804) made inroads with his invention of the semple, a device which replaced the drawboy. The semple was also removable, so it could be transferred from loom to loom, thus saving a lot of set-up time. These and other improvements led to the invention of the Jacquard loom. In 1801, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, (who at the age of twelve had apprenticed to his father as a drawboy in Lyons), devised a system of perforated cards that mechanized this procedure, and the textile industry was changed forever. In fact, the Jacquard loom was the essentially the prototype for the computer.

The British silk industry had been able to prosper and compete with the older, more established French textile industry because they benefited from various pieces of legislation aimed at protecting the British textile industry. By the 1820s, after the repeal of long-standing embargoes on imported textiles, the English textile industry collapsed and France once again dominated the field.

Wider Connections

Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, edited by Clare Browne

The Book of Silk, by Philippa Scott

Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail, by Avril Hart and Susan North

Textile Production in Europe, Silks: 1600-1800, Metropolitan Museum of Art